Cindy Sherman in Full Disguise at the Modern

With the buzz factor on the new Cindy Sherman retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art already at full decibels, aptly descriptive words such as malleable, prescient, and chameleon-like are already sounding like clichés.

Yet, it is not just her seemingly shape-shifting originality that is so impressive in this epic collection of photographs from three decades of art making, but the evolving mastery of her medium in coaxing out the effects that allow these transformations to occur.

CLICK TO SEE MORE IMAGES

At the press preview for the show last month, Eva Respini, the exhibition curator, said the artist’s generosity was a key factor in the enduring nature of her art. In all of her 512 works to date, there are no titles. The numbers are merely inventory records that her long-term gallery, Metro Pictures, devised to keep track of them. With such open-ended offerings, she permits her viewers always and repeatedly to bring their own perceptions and narratives to the photographs. This allows her images, even the iconic ones that have defined her career, to be endlessly fresh and invigorating.

What is so fascinating in a retrospective such as this, with 171 photographs in all, is that each one commands attention in the same way it did when it was originally shown, sometimes even more given the context of the additional images around it. Such is the case with the “Untitled Film Stills” series from 1977 to 1980, where familiar and less-known works are double-hung in close proximity, allowing all of their contradictions to give each narrative a richer backstory.

Ms. Sherman seems to have grasped early what simple defining details pack the most allusions in our collective sense and memory. In these images — all invented with no literal inspiration — she uses both 1950s and 1960s female cinematic stereotypes — gangster moll, pinup, naif, sophisticate — and setting, typically urban, to imbue the sense of melodrama or ennui each grainy print evokes.

The artist, who was born in New Jersey and raised in Huntington Beach on Long Island, has been a seasonal resident of the South Fork for many years, but lives quietly here, maintaining her anonymity much as she does in New York City, where she keeps her studio. She first studied painting at the State University at Buffalo in the early 1970s, but soon found conceptual photography far more relevant to her practice of making art.

Her relationship with Robert Longo, another art student at Buffalo, would be responsible for opening her eyes to the contemporary art scene, which shaped her ideas about how she would express herself. She began looking at feminist artists who treated their bodies as subjects for art and photographs, as well as the male artists who were taking things even further, such as Chris Burden shooting himself and Vito Acconci’s dramatic physical acts of self-denial and self-gratification.

The product of one of the first generations that were glued to the television as children, she also had a penchant for masquerade and disguise, and was known for dressing in complicated getups for art openings in Buffalo and New York City. These proclivities would suit her burgeoning artistic style well, giving her a wealth of material to draw from in her efforts at transformation and transgression.

She was not known for her technical proficiency at first, but the quality of the early film stills series is wholly intentional. She learned how to print them to give them a cheap, Hollywood publicity still-style finish. That the poses are staged and melodramatic doesn’t cheapen the fun. It only draws us in deeper to what she is up to by assuming these identities and raising questions about who is ultimately in control of them, whether it is she as object, subject, or artist, the viewer, or society at large.

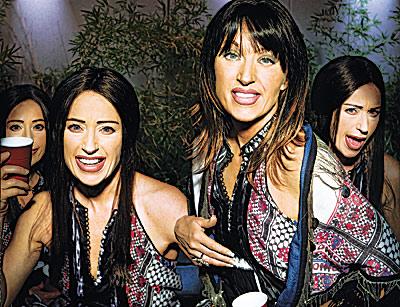

There are two big wow moments at the beginning of the show. The first is the huge photomural she devised for the installation with surreal photo images of her, several feet tall, wrapped on the exterior walls of the show. Just inside, the first gallery gives a boffo glimpse of highlights from her career, some familiar and some surprising. They run from early headshots of her simply made up to look like different, almost cartoonish characters to one of her fashion shots, a dystopian sex picture, and a mock death scene featuring her lifeless face and neck as dirt-caked insect fodder.

The room is so succinct and perfectly edited that in one sense you almost don’t need to see the rest of the show. In another, it is the perfect segue into each additional room. The more overpowering urge is to proceed to see what is in store next.

Thematically arranged, the galleries are composed sometimes completely from one period or series. In other cases they might bridge decades, allowing works that may not often be seen together a chance to benefit from cross-referencing. These include a room devoted to her reactions to fashion from several decades alternating with a gallery showing only her centerfolds series from 1981. Another cross-decade survey looking at her backgrounds and narrative space is followed by a room with several series that take her almost entirely out of the pictures, but are late 1980s and early 1990s reactions to things such as AIDS and censorship in the arts. These issues were at the forefront of artistic concerns in those years.

The history portraits occupy one cohesive space, painted in a rich burgundy to offset their opulence. The headshot series and her society portraits also have their own galleries, leaving other spaces for explorations of the fantastical and macabre and her early cutouts and animation.

There is so much to see and all so well edited. In the words of the curator, who worked with Ms. Sherman to devise the mix, their goal was to “select the best examples of the best works.” Each room is its own celebration, but certain ones do stand out such as the galleries containing the film stills, the sex and disaster series, the history series, and the society portraits.

Perhaps it is their cohesion that helps sell the works’ strengths in these galleries, but each of those rooms packs a wallop. Whether it is the abject horror of the rotting food and pieces of humanity in the disaster series or the odd personification in the photos of prosthetic and doll parts uncannily posing as human procreation machines in the sex series, those images never lose their power to shock and awe. But at the same time, her ability to make or impose herself into classic icons of art history in parody or homage elicits a similar response.

The 2008 society portraits show the desperate measures to which women will go to continue commanding attention at an age when most are relegated to invisibility. These pictures evoke empathy even as they make us cringe. In this series, her manipulation of makeup, lighting, and perhaps some Photoshop magic to mimic bad cosmetic procedures forces us to remind ourselves that we are still looking at that same woman from the film still series and how much manipulation it took her to look this way. It is one thing to transform yourself into a clown. It is quite another to make yourself look physically altered from surgery. Those pictures sting, not because they are made to look like anyone in particular, but because they could instead be any one of us in the not so distant future, new visual clichés for our current age.

“Cindy Sherman” is on view through June 11.