A City Reclaimed

“Berlin for Jews”

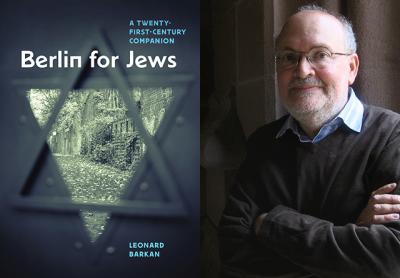

Leonard Barkan

University of Chicago Press, $27.50

Leonard Barkan is a Renaissance man, in more ways than one. A Princeton professor, he’s also a classics man, an art history man, an archeology man, an architecture man, a man who loves to travel, and a Jew who has spent much of the last couple of years in Berlin.Who better to write a book with a title like “Berlin for Jews”?

The title might be understood as simply describing a guidebook for Jewish tourists, and, indeed, it is partly that: Mr. Barkan suggests that a first-time visitor immediately buy a transit pass and board the M29 bus line to see sights like Checkpoint Charlie, the Berlinische Galerie, and the shops on the Kurfürstendamm. There are maps, reproductions of old portraits, and photographs of the city, most of them taken by Mr. Barkan’s talented spouse, Nick Barberio, that provide purposeful orientation.

But the title also suggests a question: What, besides a geographical area, was pre-Nazi Berlin for the significant minority of Jews who lived there and formed a culturally, artistically, and financially significant part of German society? And what is it for us — and for Mr. Barkan, who says he’s having a love affair with the city — today?

To answer the first of these questions, Mr. Barkan takes us to a cemetery, Schönhauser Allee, which he presents as “Jewish ground zero,” a physical reconstruction of the city’s history from the point of view of its Jewish residents. Its monuments are “a thesaurus of Jewish family names” and “a riot of majestic titles,” and form a catalog of the architectural fashions in which wealthy Germans memorialized themselves, ranging from Romanesque to High Gothic to Renaissance and beyond; they are a critique of that culture itself.

“Ornament defines culture,” Mr. Barkan observes, and these highly ornamented tombs testified to a people determined to acquire a culture that was not bequeathed to them by their forebears, and acquired not always gracefully but with great self-confidence: “If this be kitsch, they made the most of it,” he comments.

Trained as a close reader of texts, Mr. Barkan brings the cemetery to life. He learned German in school when he was 12, growing up in New York, having already picked up Yiddish at home, and he tells us that there is “common ground between the language of the Nazis and the language of their most abject victims.” Upwardly mobile American Jews like the Barkans, especially in New York, had always felt an affinity with German, “the preferred language and civilization,” the language of science, philosophy, and classical music.

But his parents spoke Yiddish to each other when they did not wish young Leonard to understand (though he picked it up quickly), and he does not hesitate to drop a Yiddish expression into his fluid, readable prose when it expresses something that has no precise equivalent in English — like tchotchkes, the particular kind of knickknacks found covering every horizontal surface in a Jewish family’s home.

Mr. Barkan turns next to the Bayerisches Viertel (the Bavarian Quarter), where those who couldn’t afford grand houses of their own occupied perhaps the world’s first “luxury multiple housing” and which was known at the time as “the Jewish Switzerland” — perhaps because it was a safe haven even before the need for a haven became brutally apparent. For Mr. Barkan it possesses “the quintessential status of what it means to me to be a Jew.”

Berlin’s Jewish community “believed themselves to be Germans, just like their Christian neighbors,” and produced, in 1929, a volume called “The Jewish Address Book of Greater Berlin,” whose oddity Mr. Barkan explains through a fanciful analogy with another minority simultaneously privileged, tolerated, and oppressed: What if prominent gays got together and produced “The Homosexual Address Book of Greater New York”? It too would be the challenging expression of “separatist and assimilation impulses.”

The rest of Mr. Barkan’s book is devoted to three prominent Jewish Berliners, carefully chosen to embody the zeitgeists of their eras. The first is Rahel Varnhagen, the unlikely proprietress of a salon — a group of distinguished artists, thinkers, and culture mavens met to engage in brilliantly witty dialogue. She was what Mme. de Stael was to Paris, what Perle Mesta was to Washington: the glue that bound together the cosmopolitan essence of a city. And she attained this status without a fortune or great personal beauty, apparently because of her extraordinary conversational abilities — like Dorothy Parker presiding over the Round Table at the Algonquin two centuries later, but without (pardon the pun) her waspishness.

Beethoven found his way to Rahel’s house, along with Mendelssohn and Rossini and the writers Kleist and Heine, as well as the nephew of Prince Louis Ferdinand. What was remarkable, and untrue of her later counterparts, was that Rahel was a Jewess — and that this was apparently an unspoken secret kept by almost all of the people who frequented her house.

James Simon, Mr. Barkan’s favorite Berlin Jew, is described as “bourgeois, liberal, statesmanly, global, supremely generous in giving and bashful in accepting thanks,” a man who almost single-handedly stocked the museums of Berlin with vast collections of important and valuable antiquities. The Zionist Chaim Weizmann took him to be a collaborator with the nascent Nazi movement, calling him “the usual type of Kaiser-Jüden . . . more German than the Germans.”

And it is true that he was on close terms with Kaiser Wilhelm, his partner in the acquisition of archaeological treasures from the Middle East, including those of Palestine. But it is also true that Simon’s name was removed from the exhibits he had bequeathed to the museums of the city, shortly before his death in 1932, though the breathtaking exhibits themselves remain.

I had never heard of Rahel Vernhagen, and Simon only vaguely, but every academic in the humanities is familiar with the estimable theorist Walter Benjamin — though having read him did not prepare me for Mr. Barkan’s portrait of the scion of a wealthy and cosmopolitan family that celebrated both Rosh Hashana and organized Easter egg hunts, a man driven by sexual impulses, an urban flaneur nevertheless unable to achieve worldly or academic success, and ultimately driven into exile and then to suicide.

Yet he was the forerunner of modern writers as diverse as Jane Jacobs, Jacques Derrida, and Roland Barthes. He was a writer who claimed membership in what he believed to be the elite stratum of intellectual achievers, who were, he explained in “Berlin Childhood Around 1900” (a project not very dissimilar from “Berlin for Jews”), of necessity Jewish. Benjamin, for Mr. Barkan, seems to epitomize the paradoxes of being Jewish in Berlin — paradoxes that World War II did not put an end to in a city whose great project has been to rise from the ashes of almost total physical destruction and, partly through acts of atonement, reclaim its humane status.

Since most of the book concerns prewar Berlin, one cannot escape the unvoiced tension between the upward mobilization and growing confidence of Berlin Jewry before 1930 with what we know is, sooner or later, coming. It reminded me of the 1782 novel “Les Liaisons Dangereuses” (perhaps better known as the 1988 film “Dangerous Liaisons”), in which French aristocrats sport and connive in decorous languor, oblivious of the fact that in a few years the French Revolution would take its bloody revenge on their privilege and decadence.

That Mr. Barkan can make a study of people whose homeland devoured them entertaining and palatable is a stunning achievement.

Richard Horwich, who lives in East Hampton, taught literature at Brooklyn College and New York University.

Leonard Barkan, a former wine columnist for The Star, used to live in Springs.