Claims Town Overstepped Legal Authority

Last week, the Town of East Hampton was poised to remove the lien it applied to a property on Montauk’s Fort Pond Bay because of the resident’s failure to pay his 2010 tax bill, which included a surcharge of $19,700 for removing cars and equipment that the town alleged had posed a danger to the community.

The offer to remove the lien was part of a settlement agreement that the town proposed to the property owner, Tom Ferreira, who declined it, saying that the strings attached would preclude any effort to recoup losses.

At issue — with perhaps far-reaching implications — is Mr. Ferreira’s contention that the civil servants who made the determination that he was in violation of town law, and who wrote the summonses that eventually led to the seizure of his property and the subsequent lien, lacked the authority to do so.

After removing the cars, car parts, and garage-related material from Mr. Ferreira’s property at 63 Navy Road three years ago, the town registered its lien with the county’s department of taxation and finance, and Mr. Ferreira, fearing the loss of the house that has been in his family since shortly after World War II, filed an Article 78 action against the town in State Supreme Court. The suit, filed on Oct. 10, 2010, charges that his constitutional right to due process was violated.

During an appearance before Judge Peter H. Mayer last week, Robert Connelly, an assistant town attorney, requested an adjournment. It was one of several such requests made by the town since the suit’s inception. According to those close to the case, Judge Mayer had recommended, in the strongest terms, that the parties come to a settlement before the Jan. 31 hearing.

That the town had made a settlement offer came to light in East Hampton Town Justice Court last week when Thomas Horn, a former East Hampton Town fire marshal, safety officer, and one of Mr. Ferreira’s lawyers, brought Justice Lisa R. Rana up to date on negotiations between the town and his client. Mr. Horn was in court discussing a separate matter regarding Mr. Ferreira.

According to Mr. Ferreira, he was given the town board’s settlement offer just hours before Judge Mayer’s deadline: The lien would be lifted if he agreed to hold the town harmless in the future regarding the events that led up to the removal of his property. He declined.

Repeated calls to John Jilnicki, the town attorney, and Mr. Connelly to confirm the substance of the deal were not returned.

“For nearly a decade my family and business have suffered due to the actions of the [Bill] McGintee administration and previous town boards. I thought justice might be found in the State Supreme Court, where the judge has tried to settle the matter since last summer,” Mr. Ferreira said.

“The town received adjournment after adjournment from a very patient judge. With less than 24 hours until the judge’s final deadline, I received my first written offer from the town. I would have gladly taken it, but my only precondition was not there,” Mr. Ferreira said, referring to his refusal to forgive the town’s actions that led up to the lien on his property.

On Jan. 31, Justice Mayer agreed to adjourn the matter until March 6, at which time a settlement will be announced, or he will hear opening arguments in a trial whose outcome could have implications well beyond Mr. Ferreira’s case.

Mr. Horn is not serving as Mr. Ferreira’s attorney in the Article 78 suit. He was hired to help Mr. Ferreira negotiate a settlement. “My role in it was to act as a negotiator. The subject of the 78 was entering his property. The property was entered, things were destroyed and taken away,” he said. “I sought to resolve that. An agreement was not reached.”

Mr. Horn said he believed his client was offered the settlement after the town board learned through its attorneys that the lien itself had not been registered with the county with the appropriate certification, an allegation that the town’s tax receiver, Monica Rottach, has disputed. The county purchased and assumed the lien from East Hampton Town on Aug. 10, 2010.

Mr. Horn said the case against his client leading up to the lien was, like the execution of the lien, illegally prosecuted by agents of the town via trespass, false accusations, and by issuing summonses without the authority to do so.

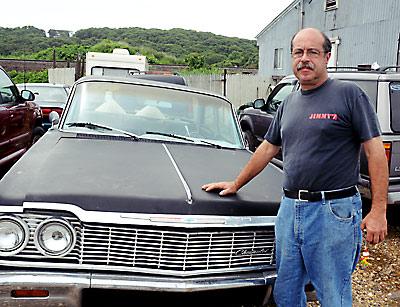

Mr. Ferreira, a mechanic, has a pre-existing right to repair cars at his Navy Road property, within a bayfront community upzoned from industrial to residential in 1982.

The current impasse started with accusations that Mr. Ferreira was operating a garage illegally, allegations that were disproved when town records showed that in September 2003, his Automotive Solutions, while perhaps less than scenic, was deemed a pre-existing, nonconforming use of his property. Mr. Ferreira held, and holds, both state and town licenses to operate an auto repair business. Nevertheless, complaints about Mr. Ferreira’s yard continued.

On June 18, 2009, the town board unanimously authorized an enforcement action, pursuant to the town code’s chapter on litter, to remove material dangerous to the public’s health, safety, and welfare. The board was acting on the continuing complaints of neighbors as well as on the advice of Dominic Schirrippa, a code enforcement inspector and director of Ordinance Enforcement at the time.

On at least two occasions beginning in March of 2008, Mr. Schirrippa and Kenneth Glogg, also an ordinance inspector, declared that Mr. Ferreira’s “abandoned cars, car parts, tires, propane tanks, and other combustible materials . . . contain gasoline, oil, possibly diesel fuel which, when ignited, would lead to possible catastrophic consequences.”

But, in a letter dated the day before the board made its decision to seize Mr. Ferreira’s property, James Dunlop, a town fire marshal, wrote: “No violations of state and local code were noted” during an inspection of Automotive Solutions the month before.

Mr. Ferreira was cited for violating the town’s litter statutes.

On June 22, 2009, Trinity Transportation, the town’s outside contractor, hauled away 12 vehicles and other material from Mr. Ferreira’s property and charged the town $9,850 for the work. Trinity visited 63 Navy Road again later and removed eight more cars and other material, charging the town another $9,850. East Hampton billed Mr. Ferreira for the expenditure, and when he was unable to pay, imposed the lien.

The seizure of Mr. Ferreira’s property went forward despite the fact that the case against him was still before East Hampton Town Justice Court. Pete Hammerle, a town councilman at the time, said it was the feeling of the board that Mr. Ferreira’s requests for a trial were a delay tactic.

However, Pat Mansir, also serving on the town board in 2009, while at first voting to remove material from Mr. Ferreira’s yard, then voted against hiring Trinity Transportation.

She said at the time that town workers had balked at removing material from a Maidstone Park property owned by Rian White earlier that year. She said there was a similar uneasiness about the legality of the Ferreira removals among town workers. “They felt we were going too far,” Ms. Mansir said.

“Were we stepping on someone’s constitutional rights? When it came right down to it, the [town] attorneys didn’t seem that comfortable. So we stopped, and hired from the outside,” she said of the Rian White case. “Same with Ferreira. It was a bad decision,” Ms. Mansir said.

Mr. Ferreira said on Monday that he refused the town’s deal for a number of reasons. There was the question of the $140,000 in vehicles and materials taken from his property, attorneys fees, as well as the overriding fact that he believes the town had overstepped its legal authority from the start.

Mr. Ferreira claims that the town’s agents who wrote the summonses that eventually led to the Trinity Transportation’s visits to his property were code enforcement “inspectors,” not code enforcement “officers.” Mr. Horn claims there is a fundamental difference.

In 2007, apparently in the interest of saving money (inspectors are paid less than officers) the town board decided to leave the job of code enforcement in the hands of civil servants with the rank of inspector.

Although the board had proposed a law in October of that year that would have allowed the town to empower inspectors with greater enforcement authority, as provided by the state and county, a resolution that would have accomplished that met with public opposition and was not passed.

“All the things they were writing is enforcement. They had no right. After 2007, the town can’t argue what they have now does the job,” Mr. Horn said.

Patrick Gunn, the town’s public safety division administrator and an assistant town attorney, disagrees. Mr. Gunn said he could not comment on Mr. Ferreira’s Article 78 proceeding, but as to needing a resolution of the town board to give ordinance inspectors the authority to enforce the town code, he said, “I believe they are authorized to enforce the code.”