Climbing Out of the Basement

When I was 8, my artistic parents divorced and my mother married an intelligent lawyer who took us from a small house to a much bigger house. The basement in our new house is where I learned to box.

I was like a small mole, burrowing down into the dark, dank soil of that basement, and it quickly became my new home. It proved a refuge from the verbally violent atmosphere my mother unwittingly got us into. Boxing became my passion. The heavy bag, the light bag, and the brown leather, 16-ounce boxing gloves became my allies. I was a young boy and didn’t do introspection too well; all I knew was punching a heavy bag felt really good.

The rigors and ecstasies of boxing lasted throughout my childhood. Anger became an exciting and profitable emotion, and now that I knew what to do with it, I refused to give it up. Boxing was brutal and bitter, but I loved it. At least that’s what I told myself.

The truth was I hated boxing as much as I loved it. Boxing was my successful dysfunction.

The angry dropouts in school became my tribal family. Ours was a rough clan of punks whose cardinal rules were “Shut up or put up” and “Never start a fight, but always end it” and “Walk softly and carry a big stick.” Our pastimes were sports, hanging out in town, and neglecting homework.

For me, the ultimate goal of my dark, angry existence was to one day fight in Madison Square Garden for a Golden Gloves title. Throughout my school years I honed my arms, chest, and legs in preparation for my forthcoming epic battle in the Golden Gloves.

Growing up, I purposely ignored my mind’s development. My deep, underlying belief was in the strength and nobility of my body. Unlike my belligerent stepfather, who battered us with his intelligent tongue, my body was my weapon, not my brain.

At 18, I finally entered the Gloves. Week after week, I beat my opponents until I reached the finals. The night of the finals, I was sick with the flu and weighed six and a half pounds lighter than normal. Weakened, but still confident, I stepped through the ring ropes of Madison Square Garden and lost a close three-round decision. Losing was horrible.

Soon, my boxing family began to break up, too. Some guys entered the pro boxing ranks, some went to work, and others landed in jail. Somehow I squeaked into college. I quit boxing as if I were quitting a drug. I was afraid it would fatally distract me from my studies, and I didn’t want to become an occasional boxer.

So I plunged into a life of books, libraries, and endless studies. I began hitting books instead of people. The classroom became my ring, but I had to work double-time in order to overcome my lackluster academic past. I rarely spoke of my previous life. There were too many clichés and preconceptions about flat-nosed pugs to overcome.

Years later, in my mid-30s, I found myself working as an English teacher in New York. For me, becoming a high school teacher was like a criminal returning to the scene of the crime. I had always convinced myself that I was born with more fast-twitch muscle in my body than quick synapses in my brain. College had proved to be an emotional roller coaster, but it was there where I discovered that punching out a perfect paragraph was fundamentally more profitable and exciting than punching someone’s face.

One afternoon, after teaching school, I entered a local boxing gym. Although I had never truly abandoned boxing, it set about saving me once more — this time from a gnawing sense of middle-aged alienation and hollowness. I didn’t drop to my knees in great happiness or feel a rush of adrenalin. I was older and wiser, and the youthful fantasy of Golden Gloves redemption had long melted away.

When I first hung up the gloves as a kid, I was relieved not to be getting smacked on the nose anymore. Life was gentler. I could eat juicy hamburgers and tasty cupcakes whenever I wanted, but I always felt as though something had been subtracted from my flesh. My blood never pumped so fast. Did I miss the human contact?

I began training again.

One day, the gym owner called me over. “Wanna be my head coach?” he said. “You c’n work nights, after teachin’.”

I looked at his damaged face, the sweaty fighters, and the grimy gym. What I once saw as brilliant, beautiful, even magical, I now saw as ordinary, ignorant, and even pathetic.

Was I too soft for this again? Was I more comfortable with the civility of teaching?

“In’erested?” he slurred.

New York City is the mecca of boxing, and there is truth in that name. Many confused young boys have started out as punks in these dark, violent gyms, fought in the Golden Gloves, and ended up world champions. Two of my friends did. But did I want to be part of this wild, dangerous, stupid, crazy sport anymore? Beating people up? Damaged faces and brains?

“Well?” he said.

Did I want to burrow down into my stepfather’s dark, dank basement again?

I looked at the man’s flat nose. “Boxing is stupid!” I said to myself. “I hate boxing. I hated it the first day I laced up my first pair of gloves down in my basement. I hated it 10 years later when I quit. But boxing saved my life. It was the bloodsucking leech that fed upon my anger, my hurt, my hate, and my fear. Boxing purified me. That’s why I love it.”

“Okay,” I told him.

A month later, a middleweight named Denny walked into the gym. “You the coach?”

I nodded.

“I wanna enter the Gloves,” he said, dropping his duffle bag to the floor.

What personal pain had brought Denny here? Did he have the same appetite for violence that I once had?

He continued looking at me.

Was this the circle of life? There were still so many unhappy memories breathing in my gut about my stepfather’s sad basement. Could I convince myself that by coaching Denny I could sculpt beauty into his body and brain? When a kid moves sweetly, is that art? Does a coach chisel a human statue?

“Why don’t you get outta here and learn how to write a perfect paragraph instead of learning how to throw a perfect punch,” I almost spit.

“I need a coach,” he said, rolling his wide shoulders.

I stared at Denny and saw my own face. “Okay,” I whispered, “suit up.”

Sure enough, Denny’s past was miserable: a mother’s suicide, a father’s death, and his own heroin addiction. I watched him gracefully punish the heavy bag and murder his reflection in the mirror. Here was a boy-bomb with beautiful muscular violence just begging to be molded.

If Martha Graham can sculpt a ballerina, I can sculpt a fighter. If she can educate toes, I can educate fists.

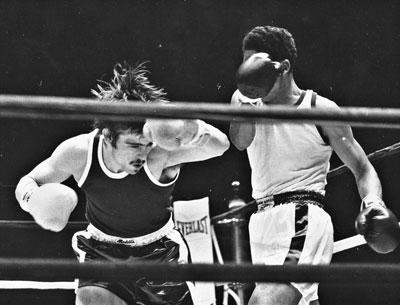

Three months later, I pried the ring ropes open with my foot and arms and Denny stepped into the ring to fight for the Golden Gloves middleweight title in Madison Square Garden. We looked at each other silently, but at the same time held back, afraid of what each other’s eyes were saying. There was a patina of Vaseline and sweat on his chiseled face.

The bell rang. I sat in the corner and watched him pound out an elegant, passionate, and lopsided decision over his opponent. Denny was a thing of great beauty — a wonderful work of art.

Boxing is insane. But it’s a healthy insane.

As the referee raised Denny’s hand in victory and the crowd cheered its approval, I realized that I had climbed out of that dark basement and a part of me was up in that ring with him.

Peter Wood, an English teacher at White Plains High School who spends summers in East Hampton, is the author of “Confessions of a Fighter: Battling Through the Golden Gloves” and “A Clenched Fist: The Making of a Golden Gloves Champion,” both from Ringside Books. The 2014 Golden Gloves wrap up April 17 at Barclays Center in Brooklyn.