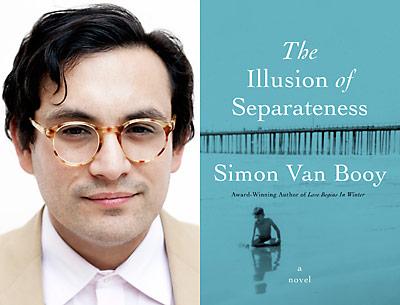

Closer Than You Think

“The Illusion of

Separateness”

Simon Van Booy

Harper, $23.99

As the title of Simon Van Booy’s gentle and lovely new novel, “The Illusion of Separateness,” might suggest, people are connected and intertwined in ways that are not always immediately apparent. Sometimes the manner people are linked never becomes apparent to them at all, but that does not necessarily signify a lack of connection.

The book — beautifully and poetically narrated in the third person from the viewpoints of several different characters — opens with Martin, a janitor at a retirement home in Los Angeles in 2010. Martin grew up in a bakery in Paris. “When Martin was old enough to begin school, his parents seated him at the kitchen table with a glass of milk, and told him the story of when someone gave them a baby.” Then his parents tell him, “Our love for you . . . will always be stronger than any truth.” When Martin is a teenager the family moves from Paris and opens the Cafe Parisienne in L.A.

For a long time now, he has been aware that anyone in the world could be his mother, or his father, or his brother or sister.

He realized this early on, and realized too that what people think are their lives are merely its conditions. The truth is closer than thought and lies buried in what we already know.

One day the rest home where Martin works welcomes a new resident, Mr. Hugo, whose head is badly deformed because as a Nazi soldier he was shot in the face during the war. He collapses and Martin rushes to cradle him. Mr. Hugo dies in Martin’s arms.

The next chapter is from Mr. Hugo’s point of view in Manchester, England, 1981. He is a lonely, solitary man with a disfigured head who befriends the son of his new next-door neighbor. “She was from Nigeria and spoke English gently, words handed, not thrown.” One day she knocks on his door and asks Mr. Hugo to child-sit Danny, as it is an emergency and she must go out. The two bond, and though Danny is having trouble learning how to read in school, Mr. Hugo manages to teach him using a combination of creative strategies and some chocolaty bribery.

Two months later, a breakthrough over bedtime drinks.

After ten minutes of staring at a container of chocolate powder, the word instant burst through Danny’s small lips.

He ran around the house screaming.

Not long after that, his mother gave me permission to take him to the library, where Danny taught Mr. Hugo about dinosaurs, comets, gold miners, and steam.

Next we meet Sebastien in Saint-Pierre, France, 1968. He is a boy and has found an old black-and-white photograph of a young woman in front of a hot dog stand and Ferris wheel. In the next chapter, John in Coney Island in 1942 takes a picture of his love, Harriet, in front of the Ferris wheel. He will take the photo with him when he goes off to be a pilot in the war.

The links and interconnections begin to become increasingly apparent, though they are like images seen dimly through a fog and we are still not sure of the significances, nor if these characters will ever actually know these links.

Amelia is in Amagansett in 2005. She is blind. She is the granddaughter of John, who flew in World War II. She tells us that “In summer, I sleep with my windows open. Night holds my body in its mouth.” And, “In this second darkness, my desire flings itself upon a world of closed eyes.”

We encounter John chapters more regularly now: first in France in ’44 when his B-24 is shot down, and then five years earlier in ’39 on Long Island, where his family owns a diner, and while “Across the ocean, Europe smoldered,” in the U.S. the Depression is happening.

His parents were quiet people. During the Depression, families they didn’t recognize came in and ate quickly without talking. When the check arrived, it was always the same: fathers rifling through pockets for wallets that must have been dropped, lost, or even left in the pew at church.

John’s parents always gave the same answer. “Next time, then.” They figured it was going on all over the country, and had agreed never to humiliate a man in front of his children.

In the years following the Depression, John remembers his father calling him over to the counter from time to time as he sorted the day’s mail. Sometimes the envelopes would include a letter, and once a photograph of a house with children standing in front of it. But mostly they just contained checks for the exact amount of the meal, folded once, and with no return address.

Back with Mr. Hugo in Manchester in 2010, we learn more of his story, from being shot in the head in the war and winding up an unknown patient in a Parisian hospital to becoming a janitor. Many of the later chapters of the book juxtapose Mr. Hugo’s time during the war and John’s time after his crash in France. At one point Mr. Hugo says that he wanted to die, “Yet here I am, years later, between this page and your eye. Part of someone else’s story.”

He gets a letter from Danny, the boy he helped to learn to read. Danny is now a famous film director in Hollywood, and he wants Mr. Hugo to come to Los Angeles so that he can help him.

Like the part about John’s family helping people during the Depression and years later getting paid back in the mail, “The Illusion of Separateness” is filled with circular kinds of pay-it-forwards. People help others or show kindnesses, and sometimes, later, get something in return without even knowing it is coming back to them from their own deeds. They are indeed parts of one another’s stories. Like people wandering blindly in the woods at night, they brush close to each other, not always sensing each other or knowing their connections.

It is a nice metaphor for all of us humans wandering around on this fragile planet. We are more interconnected than we imagine.

Michael Z. Jody, a regular book reviewer for The Star, is a psychoanalyst and couples counselor with offices in Amagansett and New York City.

Simon Van Booy, a former South Fork resident and frequent visitor, teaches at the School of Visual Arts in New York. His previous novel was “Everything Beautiful Began After.”