Cloudbusting

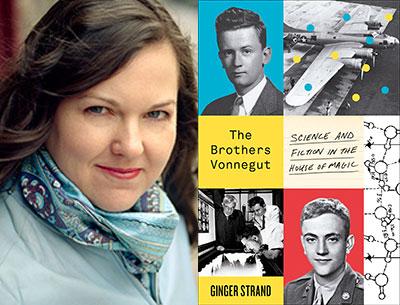

“The Brothers Vonnegut”

Ginger Strand

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $27

In the prologue to his novel “Slapstick,” which he called “the closest I will ever come to writing autobiography,” Kurt Vonnegut wrote, “My longest experience with common decency surely has been with my older brother, my only brother, Bernard. . . . We were given very different sorts of minds at birth. Bernard could never be a writer. I could never be a scientist.”

In “The Brothers Vonnegut: Science and Fiction in the House of Magic,” Ginger Strand provides a vivid and fascinating portrait of those two different minds.

The book focuses primarily on a seven-year period from 1945 to 1952 when Bernard worked at the General Electric Research Laboratory in Schenectady, N.Y., and Kurt was struggling to establish himself as a writer while working in the G.E. News Bureau, the company’s publicity department. Although Kurt’s name and work are now well known, at the time it was Bernard, an M.I.T. graduate with a Ph.D. in chemistry, who was making his mark as a researcher and inventor.

During World War II, he worked as a research associate at the Chemical Warfare Service laboratory on methods for deicing aircraft. When he arrived at the G.E. Research Laboratory after the war, it was known as the House of Magic, and its catchphrase was “Are we having fun today?” The scientists were encouraged to follow their own curiosity and to conduct pure research as well as to pursue work with immediate and practical applications; the result was a seemingly endless line of new inventions.

At G.E. Bernard was involved with two other scientists, the Nobel laureate Irving Langmuir and his assistant Vincent Schaefer, in what became known as Project Cirrus, experiments with cloud seeding and weather manipulation. While Langmuir and Schaefer first experimented with the use of dry ice in seeding to produce snow, it was Bernard’s discovery of the use of silver iodide that held the real key for more consequential results. The implications of their work were far ranging, not only scientifically but also commercially and militarily. The ability to control the weather held enormous benefits — precipitation for drought-stricken areas, the redirection of potentially cataclysmic hurricanes, or the transformation of desert landscapes into productive farmlands.

That ability, however, could also possibly provide the military with a powerful weapon. In the post-Hiroshima world, the idea of weather manipulation, a weapon potentially even more powerful than the atomic bomb, held great interest as well as uneasiness. (G.E. ceded responsibility of Project Cirrus to the military, in part, to indemnify the company from any legal responsibility from unintended weather-related damage.)

The work was also scientifically controversial. Meteorologists at the Weather Bureau looked skeptically at these interlopers — what did three chemists know about weather and weather patterns — and refused to acknowledge that cloud seeding worked without fully understanding the mechanism. They established their own Cloud Physics Project to check and challenge the claims of the G.E. scientists.

Kurt had a firsthand view of work at the House of Magic and the burgeoning and beneficial relationship between G.E. and the military as he worked in the company publicity department, a position he gained through Bernard’s suggestion. Throughout his time at G.E., however, his aim was to make his tenure there as short as possible. He was working diligently at learning to be a writer amid an increasing pile of rejection slips. He was encouraged and assisted by his wife, Jane, who gave him the courage to take the idea of writing seriously. Together they shared the dream of a life devoted to literature and art rather than science.

He would find some early success placing his work with Collier’s, and when he was able to sell five stories and begin a novel, he gave G.E. his notice, moved his family to Cape Cod, and began to make his living as a writer.

Nevertheless, G.E. had given him something important as a writer. During his time in Schenectady, Kurt feared catching “G.E. disease” — becoming a company man and conforming to G.E.’s expectations. Observing up close the work there, he grew increasingly concerned about the dangers of a technocratic worldview and scientists who developed new technologies without regard to the unintentional damage they might cause. Blinded by a “techno-utopianism,” it was too easy for them to lose sight of the effects their discoveries might have on actual human lives.

Here was all the material Kurt needed for his stories: the dark side of science and the probable future spawned by it. G.E. was science fiction. In early stories like “Report on the Barnhouse Effect” and “Thanasphere” and novels such as “Player Piano” and “Cat’s Cradle,” he would portray the G.E. corporate culture and personality and the dangers of a technocratic worldview that resulted from it. (Interestingly, the idea for ice-nine, essential to “Cat’s Cradle,” originated with Irving Langmuir, who once suggested it to H.G. Wells as the basis for a story. Wells was not interested.)

“The Brothers Vonnegut” is a well-researched and seamless mash-up of science, literature, biography, literary analysis, social criticism, and cultural history. Ms. Strand provides a well-documented look at a meteorological controversy that touched two brothers as their lives and work intersected for a brief period at G.E. She does so with clarity and deceptive ease, moving between Bernard and Kurt, allowing each to illuminate and inform the other.

One might naturally expect Kurt to take center stage in any work that features him, but Bernard and the story of weather modification emerge as the central focus of “The Brothers Vonnegut.” He personified the conflict between a love of science and a duty to humanity. His concerns with the ethical implications of the scientific work done at G.E. were the same as those Kurt would make the centerpiece of his literary work. He was the family “genius,” who eventually became uncomfortable with the idea of being the “kept scientist” of the corporation or the military.

Bernard advocated for government regulation of weather manipulation, fearing the potential damage that could be caused if his discoveries were used recklessly. He recognized the moral imperative for scientists to pay attention to the damage that they and their research might do. He left G.E. for Arthur D. Little, a private research company in Cambridge, Mass., and began researching electrical charges and thunderstorms.

Bernard would go on to become a professor of atmospheric sciences. He remained a man and a scientist of decency. And an important touchstone for a brother who happened also to be a writer.

William Roberson taught literature at Southampton College for 30 years. He now works at LIU Post.

Kurt Vonnegut lived in Sagaponack for many years. He died in 2007.