A Collector Who Gave an Artist a Legacy

How the lives of a retired, well-to-do real estate investor and an accomplished jazz-musician-turned-painter briefly converged, and how that meeting dramatically invigorated the painter’s career, tell a story about African-American art and Sag Harbor’s African-American community.

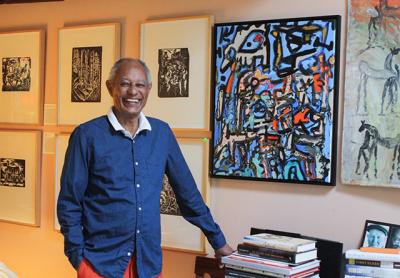

E.T. Williams Jr. told the story to a visitor on a sunny afternoon at his family compound in Sag Harbor. Now 79, Mr. Williams has been coming to Sag Harbor since he was a child. His father bought the modest house next to Mr. Williams’s own in 1933.

Over the years, Mr. Williams bought a number of houses on contiguous properties. His late mother’s cottage now belongs to his younger daughter, Eden. Another belonged to his late sister, Joanne Williams Carter, who was head of the Eastville Community Historical Society and a member of the village’s historical review board.

Mr. Williams said that his was the third African-American family of free ancestry to own the house. The first was the Hempsteads, the second the Trotts. The original structure dates from 1830. Noting the property’s history, Mr. Williams pointed to a tree in the backyard beneath which Langston Hughes wrote poetry in 1952.

Claude Lawrence lived in Sag Harbor from 1994 to 1998 and again from 2001 to 2006. Born in Chicago in 1944, he took up the tenor saxophone while in high school and played clubs around Chicago until moving to New York City in 1964.

His career as a jazz musician spanned the next 25 years. While in New York, he also moved within the art scene and met the black artists Fred Brown, Lorenzo Pace, Jack Whitten, and Joe Overstreet. He lived for a time in the same building as Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Mr. Lawrence had been an avid artist as a child and, in the late 1980s, he again began to paint and draw, his musical background finding expression in acrylic paint on paper. “I look to create work that has balance, energy, and lyricism,” he has said. “I improvise, meaning the conscious or unconscious channeling of influence. Energy is the main component.”

In 1989 he embarked on a peripatetic existence during which he lived in Massachusetts, Los Angeles, Mexico, and various points in between. He continued to paint wherever he touched down. Though self-taught as a painter, he became knowledgeable about modern and contemporary art through visits to museums, galleries, and studios.

Mr. Williams and his wife, Auldlyn, have collected African-American art for more than 50 years. Their holdings include works by Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence, Thornton Dial, Hale Woodruff, and many others.

After a successful career as a banker, Mr. Williams made his fortune in the mid-1980s with the conversion of Fordham Hill, a Bronx apartment complex with more than 1,000 units, into the largest privately financed, tenant-sponsored cooperative housing development in the history of New York City.

“Most blacks don’t have the opportunity to buy a co-op as an insider,” Mr. Williams said at the time. “Through tenant sponsored co-ops, you create home ownership and you create a community.” Thirty percent of the original owners were black.

He retired from real estate in 1992. Since then he has served on the boards of the Museum of Modern Art, the Brooklyn Museum, the Schomburg Society of Black Art and Culture, the N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense Fund, and many other nonprofits.

He not only continued to collect art, he also took up the cause of black artists he believed in, among them Hale Woodruff, Thornton Dial, and Mr. Lawrence. He met the latter when the painter lived in Sag Harbor, and he bought one of his paintings for his winter home in Naples, Fla.

Some years later, Mr. Williams learned from Martha Seigler, a Sag Harbor resident and patron of Mr. Lawrence, that the painter had returned to Chicago. Ms. Seigler had all of his work in storage and asked if Mr. Williams could contact the painter about its disposition.

In order to gauge interest in the work, Mr. Williams moved several large paintings into his house and invited Terrie Sultan and Alicia Longwell from the Parrish Art Museum to see them. They asked if he would donate three to the museum, and Dale Mason Cochran, the widow of the attorney Johnnie Cochran, wanted to buy several pieces for her Sag Harbor house.

At that point he contacted Mr. Lawrence for permission to dispose of a few works before returning the rest to the artist. Mr. Lawrence had other ideas. “I’m dying,” he told Mr. Williams. “I have lesions on my spine, and what I want most of all is a legacy, which I don’t have. Maybe you can give me the legacy.” As a result, Mr. Williams bought the entire collection.

Since 2013, largely thanks to the collector’s efforts, the painter’s work has entered the collections of more than 20 important museums, among them the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Studio Museum in Harlem, the Brooklyn Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Mr. Lawrence is now in remission and living in Oakland with a new girlfriend. Last year his work was featured in “Modern Heroics: 75 Years of African-American Expressionism” at the Newark Museum. The painter attended the opening and played the alto saxophone there.

While Mr. Lawrence’s paintings range from abstract to quirkily figurative, they are linked by his expressive use of paint and an “art brut” quality. His art also reflects his background as a jazz musician. In an extended essay on his work, the art historian Andrianna Campbell wrote, “At once harmonious and cacophonous, like an [ensemble] warming up during practice, Lawrence’s all-over compositions sometimes yield moments of recognizable figuration.”

Mr. Lawrence is reportedly reclusive, and reluctant to say too much about his work. One painting in Mr. Williams’s house, and only one, calls to mind the work of Basquiat. “What can you tell me about this picture?” Mr. Williams asked the artist, mindful of Mr. Lawrence’s acknowledgement of Basquiat’s influence. “He said, ‘Charlie Parker,’ and nothing else.” The word “Yard” scrawled at the top of the painting is an homage to Parker’s “Yardbird Suite.”