The Cricket and the Cops

What is it about old boats, wooden boats in particular? Why do they seem more worthy of respect than old cars, or even old houses? Boats that have lived at sea for years have a knowing character, a wisdom.

Have they taken on the lives of their masters or is it the other way around? Perhaps the bonding — the booted steps placed unthinking to meet the roll of the deck, the deck rolling to meet the helmsman’s feet — comes from surviving together in an alien environment. And of course there’s something of the cradle in boats.

Capt. Frank Mundus spent the last night of his life aboard the Cricket II as she lay at Salivar’s Dock on Sept. 9, 2008. He died the next day en route to his home in Hawaii. Above his bunk a sign once hung: “This is Frank’s bunk. When he wants in, you get out.” Classic Mundus.

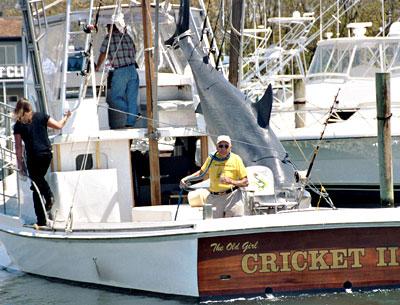

Word came last week that Cricket, the charter boat that Mundus piloted after sharks offshore for a half century as Montauk’s Monster Man, the boat that, with her ornery skipper, inspired Peter Benchley to write “Jaws,” who in turn inspired Stephen Spielberg to scare the hell out of audiences for the past three decades, will have a new home in North Carolina.

For a while after Mundus’s death, she sat on the hard at Uihlein’s Marina. Henry Uihlein and a few other business owners attempted to find a way to keep Cricket in Montauk, a landed memorial to herself and her notorious master. It didn’t take.

Frank had sold her after retiring to Hawaii in 1997, but the separation was short-lived. The dynamic duo returned to Montauk during shark-fishing season for several years, celebrities within the sanguine universe of their own design, like Roy Rogers and Trigger.

Frank told me the name Cricket came from how others perceived his profile. With sloping forehead and Roman nose, he looked like the Disney version of Jiminy Cricket in “Pinocchio.”

There was a Cricket I that Frank ran as a charter boat out of New Jersey with his brother Louis for a time, but Louis fell on hard times. Cricket II was built by a Chesapeake bayman named Tiffany Cockrell with the low-decked and beamy design of the oyster dredge boats that worked the Chesapeake. Mundus claimed Cockrell had never seen the Atlantic Ocean, and out of his imagination’s respect for its treachery, the old man built Cricket four times stronger than he needed to.

Her keel was made from a length of yellowleaf pine measuring 10 by 12 inches thick and cut from the heart of the tree. Cockrell told the trucker who brought the wood that if there was a knot anywhere in it, he shouldn’t bother unloading. The keel was notched into Cricket’s stem piece and transom. Ribs were placed close together for extra strength, as though old Cockrell had foreseen the thousands of monsters that would sashay beneath Cricket looking up. Teeth were snapped off — “like rifle shots,” Frank said — and embedded in Cricket’s planking where she was bitten by white sharks.

Cockrell bent two-inch planking over the ribs, with another two inches on top of that and half-inch plywood as a skin to which Fiberglas roving and mat were later added. She was completed in 1946.

In June of 1951, Frank fueled Cricket in Brielle, N.J., loaded his wife, Janet, 2-year-old daughter, Bobby, and a Model-A Ford on board — “I backed the boat up to a steep embankment. Got it close as I could and tied it to the trees by the stern bits and made a ramp out of planking from Cockrell’s boat yard and drove the Model-A up to the stern.” Mundus pointed Cricket northeast, bound for the Fishangri-La dock in Fort Pond Bay, Montauk.

The same stern bits that pulled the Model-A onboard would tow sharks bigger than the Ford back to Montauk on a regular basis over the years.

After Frank died, Cricket was purchased by a man named Jon Dodd and taken to Connecticut to be restored. The work proved too costly so Dodd and Capt. Joe DiBella, her previous owner, created the Cricket II Restoration and Preservation Project, a not-for-profit corporation with over 300 supporters.

On April 2, Cricket — “stripped down and is now just a bare hull with no motor, no decking, no frames, nothing” — was transported to the Bock Marine Ship Builders in Beaufort, N.C., according to Captain DiBella. “We had a police escort of 12 cars, and the Cherry Point Marine Base honor guard saluted her as we passed,” he reported. “I will bring her back to life again, but she will never go back to Montauk. Instead she will be carrying out disabled veterans and wounded warriors, plus we are working with the Children’s Cancer Center.”

That bit about a police escort, Frank would have liked that. His father worked as a cop during the summer months. Frank always likened fishing — planning the right bait, the right rig, location, all the myriad subtleties — to robbing a bank. If the fish got away, he’d say, “The cops showed up.”

I’m sorry Cricket is not in Montauk. She belongs here even as the shark-fishing craze she helped spawn morphs into a greener, catch-and-release fishery. It was something the Monster Man saw coming and approved of. The cops showed up. A good thing.