A Cultivator of Earthy Delights

The Drawing Room Gallery in East Hampton has a wonderfully colorful group show of some of its regular gallery artists on view in its front galleries, but a tiny show of small photographs from the turn of the 20th century by Charles Jones emits its own magnetic pull toward the small back gallery.

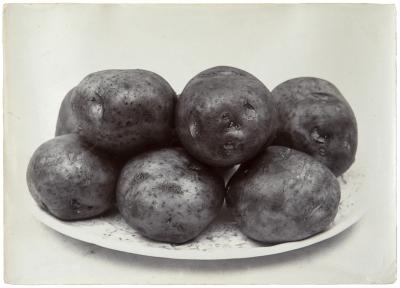

Jones, who lived from 1866 to 1959, was an avid English gardener who admired his produce so much he made it the subject of a series of glass negative photographs. Keeping the backgrounds stark and tidy, the beets, onions, potatoes, cucumbers, squash, radishes, and other earthy delights are clearly the stars of the images.

Although the images’ stark modern look would be adopted by photographers who came after him, Jones apparently was not trying to make art. Rather, he seemed to approach the objects from his garden the way botanical painters portrayed their bounty, as a record.

His titles are notations on the backs of the prints: “Potato Red Round,” “Ridge Cucumber,” “Bean (Dwarf) Sutton’s Masterpiece,” to name a few. That these prints were found in a trunk in London without their negatives and discovered at an antiques market in 1981 demonstrates how little value the photographs had accumulated since their making.

Yet these are compositions made with passion. The descriptive titles hint at colors we will never see, but the tonality brought out by the vintage gold-tone gelatin silver prints of “Radish Long Red” and “Mangold Yellow Globe” (which one assumes are golden beets) more than make up for it. Placed on a plain white ground in a tight bunch and captured from above, the radishes (at far right) look ravishing. In contrast, the beets, shown stemless, are stacked in a pyramid of three with a wall supporting them from behind. The dwarf beans lie flat but appear to dangle from their leafy stems like flowing locks from a crown. Jones’s “Onion Brown Globe” appears to be cast from bronze.

With little data and the only mention of the artist from his work as a horticulturalist in a professional publication dating from 1905, his innate preternatural talent feels mysterious and uncanny. It could easily be presumed that he was some gentleman hobbyist, but he spent his life, in the employ of a number of estates and then lived in Lincolnshire. He led a private life out of touch with the modern world and its conveniences, such as electricity and plumbing, according to a brief biography by Robert Flynn Johnson that accompanied a 1998 monograph of Jones’s photos. In the same account, there is a family recollection of how he used the glass negatives he created as cloches to protect young plants in the spring in his later years.

There are three floral studies in the group of nine photographs, and all have the same arresting minimal approach. Still, Jones’s vegetable still lifes have a gravitas and presence that are all made more impressive by their humble quotidian appearance.

The works by Stephen Antonakos, Antonio Asis, Vincent Longo, Alan Shields, and Jack Youngerman in the front gallery share a similar luminosity with the photographs. Emily Goldstein, an owner and curator of the gallery, said the works were chosen because they used color to evoke light, a welcoming thought in a time of increased darkness. Mr. Antonakos, Mr. Asis, and Mr. Longo form the core, with works from the 1950s by Mr. Youngerman and an early example of Mr. Shields’s sculpture using paper pulp over wire rounding out some of the visual themes.

The exhibitions are on view through Jan. 28.