Daddy Badass

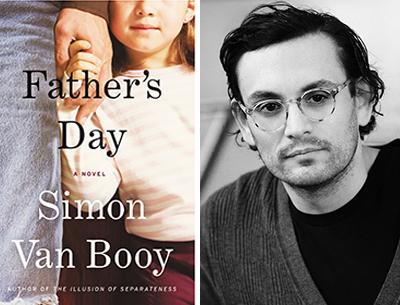

“Father’s Day”

Simon Van Booy

Harper, $24.99

“Think about it this way,” Jason the neck-tattooed motorcycle aficionado says to his adopted daughter in Simon Van Booy’s new novel, “Father’s Day,” explaining his lack of even one date during her two decades in his life, “I’m a single parent with no money, a dead-end job, a fake leg, bad teeth, and a criminal record. Plus I’m a recovering alcoholic. What loser could ever love a person like that?”

Good one, Dad, you just sent the only person in the world who does in fact love you bolting her chair and stumbling out onto the patio, trailing sobs. (Or something like.)

It passes, lesson learned, and the bond grows. And this is the story of that bond, which begins as an unlikely one between a precocious little girl, Harvey, and the beer drinker and hell-raiser who gives up the bar brawls for the nearly straight and narrow so he can adopt his dead brother’s kid. All thanks to the intuition and persistence of a social worker who saw past the hard-luck facade and recognized a potentially good parent. Because parenting, perhaps above all else, requires presence.

How does he do? Well, the two share an appreciation for TV’s “SpongeBob,” and pizza, and a certain chopper with a nickel-plated headlight and chrome tailpipes.

“We all know about the motorcycle you’re building in the garage,” Harvey’s second-grade teacher informs Jason on parent-teacher night, which he’d prepared for by digging out his best sweatpants and Band-Aiding over his tats, “and that your tacos and meat loaf are amazing — but your chicken is a little dry, I’m afraid.”

Jason may be one of life’s losers, with anger issues he deals with by secretly banging out a quick hundred push-ups, but he’s down with what the Greeks called agape, unconditional, self-giving love. That’s the thing about hearts: You never know who will get one.

Based on no stronger evidence than having read a few short stories, one could argue that a knock against Mr. Van Booy is his sentimentality. Here, however, the author, Welsh-raised, cosmopolitan, romantic in disposition, proves adept at exploring low life, recounting, for example, how Jason, five years out of stir and on a bender, once handled curbside harassment: “in one motion explod[ing] upward, driving the metal can into the man’s face, shredding the lower part of his lip,” before head-butting his accomplice into submission.

A departure, too, is the dreary Long Island setting — Chuck E. Cheese’s, the dentist in Westbury, the bowling alley in Mineola. But Harvey, with Jason’s support, escapes, first to art school and then to a job as an illustrator in Paris, presaging her dad’s visit on the day the book’s title denotes.

“Father’s Day,” naturally, isn’t as straightforward as all that. As early as page 24 a life-altering secret is hinted at, to be revealed by way of a certain document at the end of the book, but that foreshadowing easily can and maybe should be put out of the reader’s mind, as there’s so much else to enjoy along the way, from Mr. Van Booy’s muted lyricism (“Harvey did not hear the sound so much as feel it, the way a child in the womb must feel the tolling of its mother’s heart”), to the profusion of quiet domestic moments rendered in the strangely captivating way of Andre Dubus.

Much attention, for example, is paid to meals, the taking of and the preparation of. Jason, up while it’s still dark, puts coffee on first. “Then he heated some oil in the pan and dropped the sausages in one by one.” This for Harvey’s ninth birthday breakfast, complete with SpongeBob napkins and chocolate milk — all of it subsequently scuttled by a raging fever, one so threateningly high Jason abandons his sense of self-sufficiency, swallows his pride, and runs for help from the Hispanic family next door.

“The ones I’m not allowed to wave at?” Harvey asks.

“Yeah, them.”

Jason likes his coffee and cigarettes out on the patio, the better to mull things over, at times with great profundity: He worries “that they might never find each other again, once this life had ended.” When he considers the dispiriting stream of daily annoyances — a toilet that won’t flush, the broken AC, no Pull-Ups — the seesaw yet rises at the thought of those other “little things, like pizza night, playing drums, and watching cartoons, that made life worth living.”

If you’ve ever wondered about the time commitment reading fiction requires — seems a mite leisurely, doesn’t it? — that’s as good an answer as any: a reminder to simply pay attention.

Simon Van Booy is the author of two previous novels and three collections of stories. He is a past resident of the South Fork and a regular visitor.