Darkness Out East

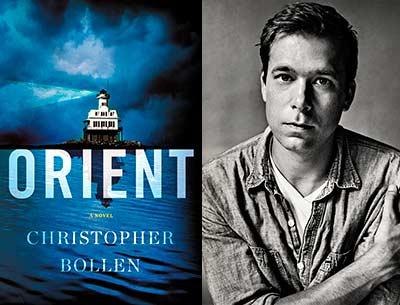

“Orient”

Christopher Bollen

Harper, $26.99

Geography matters. An author chooses to weave a tale of mayhem, suspense, and fear. What better setting than a remote hamlet, surrounded mostly by water, where there is a lot of open land and where it grows very dark at night? Add to this a tiny, entrenched population disdainful of newcomers and downright suspicious of any stranger, and you can feel the muscles in the back of your neck actively tighten.

So it is fitting that Christopher Bollen, an editor at large for Interview magazine, has chosen to locate his second novel in Orient, the easternmost point on the North Fork of Long Island, and to appropriate the place name as his title. If the locale is minute and ominous, the eponymous novel is big and fully engaging. Mr. Bollen has crafted a first-rate murder mystery set in the present moment.

Not surprisingly, Orient itself — a speck of a place the very mention of which suggests the faraway — is as important a character in this chilling story as any of the humans the author creates. Connected to the rest of the world by the thinnest filament of causeway, Orient’s smallness and remoteness are largely cherished by a few native-born, full-time residents, even as those qualities are under siege by the growing number of successful artists from New York City who seek to build opulent houses there. (“If they hadn’t been priced out of the Hamptons, they would never have made Orient their second home.”)

The tension between newcomers and old-timers — between real estate investors and the local historical board, bent on preserving the Orient they grew up in — is palpable. That tension, of course, is rooted in economic disparity. Describing the proprietor of a local organic farm stand, Mr. Bollen writes, “If darker times had left their scars, his customers’ more recent prosperity cushioned them.”

Into this less-than-bucolic scene enters Mills Chevern, a young drifter in his late teens. Mills comes to Orient at the behest of Paul Benchley, a New York architect whose roots are in Orient and who first encountered him in Manhattan. Following the recent death of his mother, Paul seeks Mills’s help in clearing multiple generations’ worth of accumulated things from the many rooms of the large Benchley home. It’s a mighty task to which the youngster proves equal.

Paul also wishes to provide Mills a kind of haven. Knowing that Mills grew up in an unstable series of foster homes resonates with Paul, whose family had sought to adopt a sickly foster child years ago, before that child died.

In time-honored mystery fashion, a couple of murders occur early on — first of a local caretaker/handyman, then of an elderly doyenne of the year-round community. Naturally, huge suspicion falls on Mills, the outsider about whom people know practically nothing. When a fire started by arson takes the lives of almost the entire family living next door to the Benchley house, the youngster is scrutinized even more closely and alienated even more from most of the people in Orient.

As though this crime streak isn’t enough, a number of grotesque mutant animal corpses show up, playing to people’s deep and dark concerns about what really goes on in the government laboratory on nearby Plum Island. Fear abounds.

Against this backdrop, Mills knows that leaving Orient will only make him appear guiltier, and that the only way to establish his innocence is to identify the killer or killers before the police do. With few resources and hardly anyone on his side, that is what he sets out to do — against all odds and with time running out.

Though we know precious little about Mills, one thing we do learn about him is that he is gay. Interestingly, not much is made of that, beyond its reinforcing his dramatic function as an outsider. (“The loneliness that engulfed him on his way to take out the trash was the loneliness of a clear-cut world.”) Most of the other characters are not even aware of the teen’s sexuality, nor does it contribute in a significant way to the overall narrative. Perhaps that signals, in this post-Obergefell-v.-Hodges era, that we are seeing the normalization of gay characters in fiction.

At slightly more than 600 pages, the length and heft of this novel should not deter any reader who appreciates an engaging mystery rich in local color. Mr. Bollen tells a fine story. Tension and interest never flag, and the final 50 pages or so make for a true page-turner. Of the final resolution to the story I can honestly say, “I did not see that coming!”

Orient has been compared elsewhere to an Agatha Christie mystery. To this author’s credit, however, he does not resort to the occasional Christie device of introducing a new character at the last minute in order to solve the crimes at hand.

In the end, of course, guilt is revealed, but one also comes away with an overarching sense of an unhappy place at the end of the world. And the ethos of that place contributes to the drama that unfolds there. “You know, I blamed you at first,” says one character to another. “But then I decided: it’s Orient’s fault. All this phony peace and quiet, like it can never quite wake itself up.”

My only regret was that I was not on Long Island when I read “Orient.” Proximity would only have imbued the experience with an even more chilling edge.

A weekend resident of East Hampton, James I. Lader periodically contributes book reviews to The Star.