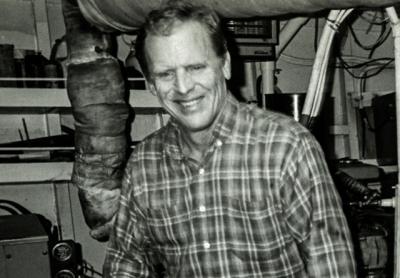

David P. Krusa, Fisherman, Writer

David P. Krusa, a former commercial fisherman who had put as much energy into developing an offshore tilefish harvest as he did writing poetry and fiction, died of congestive heart failure on Jan. 4 at home in Montauk. He was 75.

Before Mr. Krusa began targeting deepwater tilefish in the 1970s, the now-valuable fish was landed mostly as bycatch and largely in Barnegat, N.J. This shifted to Montauk after Mr. Krusa’s longline approach revolutionized the fishery. The coastwide harvest jumped from 125 metric tons to more than 3,900 metric tons by 1980, according to the Northeast Fisheries Science Center in Woods Hole, Mass.

Mr. Krusa’s innovations drew on his time longlining for halibut in Alaska around 1971, his wife, Stephanie, said.

He was born far from the ocean, in St. Louis, on Sept. 30, 1941, to Paul Henry Krusa and the former Mary Francis Cranston. His father died in a plane crash in 1945. In 1948, he and his brother and mother moved to Greenlawn on Long Island to be close to his father’s family.

As a boy, Mr. Krusa would bicycle to the Northport, Huntington, and Centerport harbors to play. At 15, he started clamming for money, often aboard a cast-off skiff that he and his brother, Chris, had been given by a yacht club to restore. For 10 years, the Krusa boys had a go at various inshore fisheries.

During the early 1960s he attended the Colorado School of Mines, studying engineering. He also went to the University of Washington, where he learned about fisheries and marine biology, and Columbia University to study writing.

During breaks from his studies, he crewed aboard a converted World War II minesweeper along with John Nolan, who would be a longtime fishing partner, chasing swordfish without much success. In 1965 he found work aboard shrimp boats off the coast of French Guiana. Subsequent travels took him all over North, South, and Central America, as well as Europe and Africa, where he learned about the people who worked the water and how they did it.

He married the former Stephanie King in 1967 and shortly afterward they drove to Alaska by way of Colorado and British Columbia. In Petersburg, Alaska, Mr. Krusa found work aboard the Betty, a 100-year-old wood halibut boat. He also learned how to catch salmon from an open skiff and tried logging until an injury forced him to leave that occupation and Alaska and return to clamming in Long Island waters.

Mr. Krusa and Mr. Nolan reconnected while working on Great South Bay, bought a shrimper from an owner in the Carolinas, and converted it for lobstering. This was the start of a 40-year partnership that expanded to crabbing, swordfishing, and tilefishing. As partners, they first commissioned twin 54-foot-long fiberglass Bruno and Stillman boats, the Deliverance and the Rainbow Chaser. As the fishery grew, they ordered two 83-foot-long steel vessels, the Restless and the Sea Capture, from Washburn and Doughty of Maine.

In the 1980s, Mr. Krusa obtained a marine surveyor’s license and established a global fisheries-development firm. He retired from most commercial fishing in the 1990s after being diagnosed with lymphoma.

In 1995, he traveled with his sons, Kipp and Lee, to assess possibilities in Mauritania and Gambia. In 1995 he also conducted an extensive study of resources on Guanahani, and other islands off the coast of Honduras, in the Caribbean.

In 2003, Mr. Krusa bought and restored a 48-foot-long John Atkins steel schooner, which he renamed Deliverance, for a trip in 2005 that reached the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Throughout his life and particularly after his illness forced his retirement, Mr. Krusa wrote stories, often about moral conflicts facing fishermen at sea. He was a founder of the Montauk Writers Group. His short stories were printed in The East Hampton Star, and his piece “Winter Trip” was included in “On Montauk,” an anthology published by the writers group.

He was also an occasional commentator on The Star’s letters pages. In 2004, he weighed in on the intersection of politics and fishing, observing, “If you don’t flip-flop your theories in the process of finding fish, the chances are — unless you are lucky — you’ll come in with an empty hold. I would rather have a competitor who is stuck in his ways than one who has the ability to change as new information is brought in.”

In recent years, he took up sculpture and woodworking, making gifts for friends and family and totems and paddles inspired by examples he had seen on the Northwest Coast. Ms. Krusa said one thing he will also be remembered for was his “outrageously frustrating” ability to win at gin rummy.

Mr. Krusa is survived by a brother, Christopher Krusa, who lives in Glen Carbon, Ill., two sons, Kipp Krusa of Nashville and Lee Krusa of Los Angeles, and a daughter, Margaret McKinnon of Willis, Tex. Three grandchildren, two nieces, two nephews, two grand-nieces, and two grand-nephews also survive. His mother died in 1994.

A celebration of Mr. Krusa’s life will be held at Sammy’s Restaurant on Flamingo Avenue in Montauk on Saturday from 2 to 5 p.m. His ashes will be spread at sea at a later date.

Memorial donations have been suggested to the East End Foundation, care of Roger Feit, P.O. Box 1746, Montauk 11954, or the Montauk Ambulance Company at 12 Flamingo Avenue, with the notation “David Krusa.”