De Kooning Through a Friend’s Eyes

By all accounts, the exhaustive and redefining Willem de Kooning retrospective on the Museum of Modern Art’s entire sixth floor is a blockbuster, and an opportunity to come to terms with the artist’s unique contribution to 20th-century art.

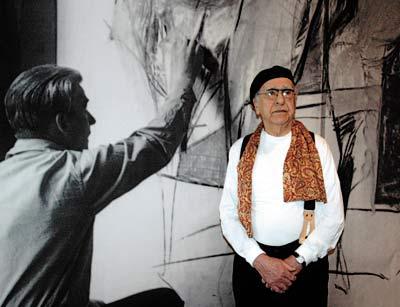

MoMA’s interpretive scholarship is exhaustively informative on its own. Yet, it was a treat to explore the show on more intimate terms with someone who was as acquainted with the artist’s working methods as anyone could be. In this respect and others, Athos Zacharias, an artist who has lived in Springs for several decades and became friends with de Kooning in the early 1950s, was an excellent tour guide for the show, which closes on Monday.

In a 1965 letter of recommendation for Mr. Zacharias for a teaching position, de Kooning wrote: “I have known Zacharias for more than 12 years personally. During those years he was, I can say, ‘one of us.’ ”

“He was, of course, much younger than most of the artist[s] who were then so very much involved with one another. But since that period, there was little self-consciousness about who was younger or older. Zacharias was as much in the middle of it as anyone.”

By “middle of it,” de Kooning meant the intellectual and critical scene surrounding the Eighth Street artists’ club (known familiarly as “The Club”) and the attendant socializing and posturing that centered around the Cedar Bar just down the street. But Mr. Zacharias, as a young artist recently arrived from the Rhode Island Institute of Design, also became close to a number of artists, as an assistant first to Elaine de Kooning, then to de Kooning himself, and ultimately to Lee Krasner, who kept him around as a workmate but also as a friend and companion. In between, he helped other artists and they, in turn, helped him.

On Dec. 14, Mr. Zacharias agreed to serve as a chaperone for the retrospective and offered some insights into what he saw in de Kooning’s paintings and his development as an artist as well as some anecdotes about what kind of person he was and what he chose to share about his art.

Mr. Zacharias recalled first meeting de Kooning at the Cedar Bar, having a discussion with him as others tried to get him to go to a table. De Kooning waved them off for the better part of an hour as the two talked about various things. Then, de Kooning said at last that he had enjoyed speaking to him. “Now, I will go join my friends,” Mr. Zacharias recalled him saying.

He moved slowly through the exhibit, passing through the early academic works and heading straight to the surrealist explorations and early figurative dissections that would become the “Woman” series, a theme he would return to repeatedly throughout his career. There was a lot of Joan Miro in those early works, he observed.

A few paintings from the mid-1930s had a similar composition and paint application to that of Stuart Davis. Mr. Zacharias said he remembered Davis visiting de Kooning’s studio. Of the oil paintings on view at the time, “Bill said that Stuart Davis called them the biggest watercolors he had ever seen,” a quip, “because Davis himself painted so thickly.” For de Kooning, whose early life as a painter was often a struggle, using more fluid and thinner paints was a way to save money, just as many used house paints as well.

During this period, Mr. Zacharias said, “You have to know he’s painting with his mind, exploring, but always painting the figure” in these early abstractions. “The straight lines, curved lines, and angled lines of his work would reveal an arm or a breast,” but he took them out of context in some of the first “Women” paintings, and that would become a recurrent theme throughout his career.

Of those works, Mr. Zacharias said, “In my mind, it’s all figurative painting. It’s the human form, but he’s giving it to you as a number of pieces, like a list: Here’s a breast, here’s a mouth, there’s an arm. Otherwise, why bother to tell us what it is.” The balance of the simultaneous flatness and three-dimensionality of the works were one of the powerful elements of his art, said Mr. Zacharias. In a later painting of two women he said “it’s wonderful to see how flat he gets the two figures. A teacher can’t show you how to do that. It must come from an understanding of other work, beginning with Cezanne.”

The later “Women” paintings, he thought, included elements of the comics in them. The extreme expressions and sometimes frenzied style and exaggerated lines, could have been early forebears of the more literal translations of comics used by Roy Lichtenstein. While the series continues to inspire controversy, Mr. Zacharias said “he was not a violent person, he was just having some fun with it.”

Although he served as de Kooning’s assistant in New York and was then his friend “I rarely talked to Bill about his art. I once asked him a question and his answer was three words. He had all these books about his paintings, works I had never seen. I asked him, ‘Bill, did you mean to paint these faces?’ He said ‘yes and no’ and walked away. It was the only question I ever asked him.”

On approaching “Excavation,” from 1950, Mr. Zacharias remarked on its airiness. “It looks a bit like Pollock. Bill would usually give you flatness, but here it’s like those aspects of space that Pollock would look at.” It reminded him of a “whole obsession with the flatness of the picture plane, the idea not to make too many holes in the plane, otherwise it would just be illustration” that dominated American art at midcentury.

Channeling influences and cross-pollination from other artists’ work was an issue when the community of artists was so tight and there was such a demand on breakthrough creativity. Mr. Zacharias said he stopped painting for a time, because he felt his work was becoming too derivative of de Kooning’s paintings.

“Soon after that, I went to his studio and he asked me ‘Why aren’t you painting?’ I had told Elaine that I found I was painting a lot like him and felt funny about it.” De Kooning brought out a book of his work and stood over Mr. Zacharias, pointing out his paintings. “Here you see I’m influenced by Picasso, here I am influenced by Soutine, here I am influenced by Miro. You are influenced by me and I am influenced by you,” de Kooning told him.

“That’s a great teacher,” Mr. Zacharias said. “It didn’t sink in at the time, but he was saying ‘It’s okay kid, you have talent, too. Learn from us.’ ” What Mr. Zacharias took away from de Kooning’s paintings was their variety, spontaneity, and dynamism. He also adopted one of the artist’s primary tools, a liner brush, typically used by sign painters, which he used in many of his paintings. “The long hairs hold a lot of paint. It’s the control of the hand that determines whether the lines are thick or thin.” Mr. Zacharias said de Kooning gave Arshile Gorky a liner brush and it was how he developed the long oil lines that characterized his later work.

The exhibit is difficult on some levels. There are so many knockouts that those works that would normally attract interest seem diminished in comparison. “Some hit you right away, others he’s just giving people a laundry list of objects and effects.” A painting like “Police Gazette” with its varied lines and forms in color prompted Mr. Zacharias to say “What more could you ask for?” But “Interchanged” nearby did not impress him so much. “I don’t think with this one he quite nailed it.”

De Kooning was an artist who “worked so hard, over and over the canvas,” Mr. Zacharias said. At a certain point a painting becomes a puzzle, “interlocked so that you can’t change one thing without affecting the other. He said he never knew when it was done. He would just walk away.”