Deep Digital

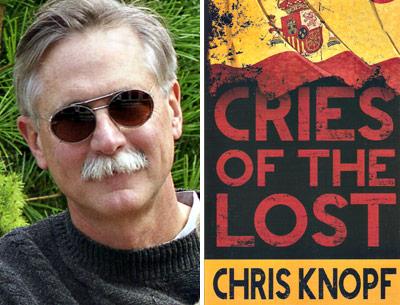

“Cries of the Lost”

Chris Knopf

Permanent Press, $28

A smartphone is a useful tool, although, say, reading a novel on one might leave something to be desired. How about reading a novel about one?

Chris Knopf has attempted a brave or foolish thing in his latest thriller, “Cries of the Lost,” maneuvering as he does proxy IP addresses, data mining, security camera video feeds, phishing, email exchanges, and Google searches to the fore of the action. The tracking is by GPS coordinates, not shoe leather, and while the sentence “She took off in the Fiat, and I followed her on my smartphone” may make you wonder if crime novels have really come to this, it can conceivably be taken as a kind of experiment, an “if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em” admission of the way we live now — surveilled and eavesdropped upon and data-ed up.

But is it tongue in cheek? Early on, our man in the digital ether, Arthur Cathcart, a researcher by trade, forever lugging around electronic equipment only an engineer could love and cozying up in nests of cables, tells us, “As in all things today, the solution began with the Internet.” You can almost hear the author’s sigh. “I searched for ‘codes and cyphers’ and settled in for a lot of reading.”

Later, “But I searched on . . . my eyes watering and my wrists and fingers literally cramping up.” (Been there! And all I was doing was perusing an online New York Times Magazine profile of John McCain.)

Mr. Knopf seems to be of two minds. He strives mightily to make the computer sleuthing gripping. “To me,” Arthur relays in his first-person narration, “a major data center that’s been around for a while is like a vast ancient ruin, wherein the fundamental structure is filled with tangled debris, crumbling walls and overgrowth. A fantastical painting of a 10,000-year-old city, beautiful yet decadent, equal parts order and chaos, and nearly infinite in scale.”

Yet at the same time — specifically, 35 pages later — through his protagonist he delivers a withering assessment of what we’ve done to ourselves: “It was an affliction of the age — too much information, not enough wisdom to make sense of it.”

The story involves millions skimmed from insurance carriers and clients and parked, in the manner of plutocrats and presidential candidates, in an offshore account, the subsequent dollar chase, an F.B.I. mole, the Basque-separatist ties of the Marxist parents of Arthur’s dead Chilean wife, and a smattering of what’s left of Spain’s fascist sympathizers.

The motivations driving the characters are various, often murky, but with Arthur it’s clear, and it’s not about the money. An “obsessive” in the face of a puzzle he can’t solve, an enigma he can’t crack, he’s willing to risk his life for mere curiosity: “I had a very hard time sharing the planet with an unanswered question. . . .”

When the expected gunplay erupts, it’s memorably at an outdoor European cafe where tables are gleefully shot up, the espresso flies, and the chic crawl for cover.

But not Arthur. Formerly wonkish, he fears not death, having been through the liberating experience of taking a bullet to the head (in Mr. Knopf’s previous book, “Dead Anyway,” a story this one continues). Roused from the resulting months-long coma, Arthur finds the head wound actually left him more interesting, more empathetic, more intuitive, more daring. Thinner. A couple of rakish scars on his slick-bald pate.

“There’s something intriguing about a man with scars,” his sidekick and love interest, Natsumi, of the glossy black hair and “Asian reserve,” reassures him. “Suggests an adventurous past.”

“Really. I have a big nose and wear glasses,” Arthur answers.

“So does Woody Allen. The nose suggests virility and the glasses intelligence.”

The book, heavy on exposition and at times description, could have used more of this, more dialogue, more sex, more of Mr. Knopf’s ear and wit.

“My mother once told me fear attracts evil forces,” Natsumi says.

“She learn that from a Zen master?” Arthur asks.

“Wes Craven.”

Chris Knopf lives in Southampton and Connecticut.