Down and Out With Nelson Algren

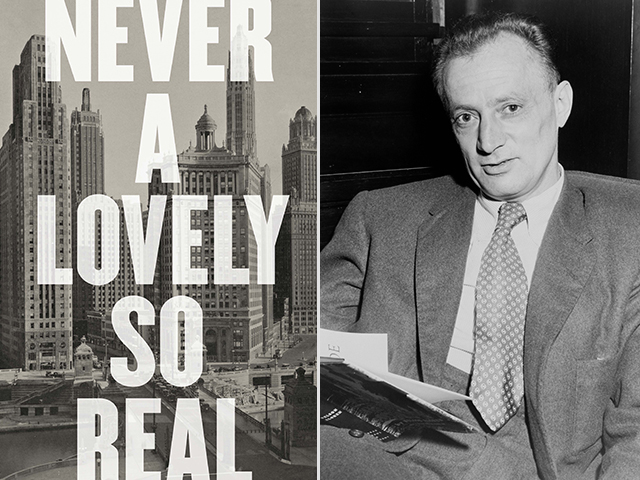

“Never a Lovely So Real” Colin Asher W.W. Norton, $39.95A rogue. A thief. Vagabond. Bounder. Ex-con. Nelson Algren was also one of the most famous authors of the mid-20th century. He knew how to write magical, evocative prose about the down-and-outers because he and his parents were exactly that. Broke. Aimless. Without even headroom to dream, so desperate were their straits. He was born in Detroit, then when he was a toddler his family moved to Chicago. Algren’s father had a garage, which he eventually lost. His mother was a lemon-sucking fury. Somehow after an okay time in high school Algren made his way to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, graduating in 1931 with a degree in journalism. It was the Great Depression. Still, he was surprised to learn that there were no jobs. Until finally, several states away, he found one. He worked for a week until he discovered he was going to be paid a nickel. But at least during those few days he had access to a typewriter. He would bum around the country, sneaking onto trains, Dumpster diving. At one point he began going to a Communist center where he was given access to a typewriter again and mentored by someone who truly nurtured him as a writer, and he began publishing some stories. Algren set out once more to find work, ending up in a tiny Texas town where he was a bit of a celebrity and a small college allowed him use of a typewriter. When he was leaving town, he visited the college office one last time and decided that the typewriter had to come with him. The police caught him several train stops along the way. He was sentenced to three years in prison. He was lucky it was cut back to five months.Nelson Algren is now an obscure name in the canon. But in “Never a Lovely So Real,” the biographer Colin Asher has set out to explore the genesis, the inner workings of this complicated author who sold millions of copies of literary short stories and novels, deeply influencing dozens of writers, notably Richard Wright and Simone de Beauvoir. Algren was a writer who came from nowhere and kept lighting firecrackers until he had a fireworks of a career, then somehow fizzled out of the writing firmament.But Mr. Asher’s task was to piece together the mysteries surrounding Algren’s career while debunking the rumors. Colleagues and critics indicated that Algren disappeared because of mental illness, writer’s block, heavy drinking, and, yes, perhaps his conviction. However, Mr. Asher makes a strong case for the fact that the obstacles Algren faced in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s arose from insidious actions on the part of the F.B.I. The novelist had been a Communist, although later he would admit that he didn’t quite understand what cause he had been supporting. Mr. Asher makes a case that Algren’s suicide attempt and mental health hospital stays arose from his inexplicable difficulties that might have been the result of federal meddling in his life. He was denied a U.S. passport several times.Algren, who’d written several novels and short stories, including three that won O. Henry prizes, solidified his renown with his groundbreaking 1949 novel, “The Man With the Golden Arm,” recipient of the National Book Award. That was the very first National Book Award ever presented: 1950. In Algren’s novel, Frankie Machine is a gifted card dealer. He’s also an addict struggling to stay clean while the card sharks are hounding him and he is trying to care for his wife, who is in a wheelchair. Algren knew all these characters well — most likely having lived hard and harder himself through many of the same travails. The 1955 film directed by Otto Preminger starred Frank Sinatra, with Kim Novak as his lover. The film was a huge hit. Algren, displaying his usual quick-to-anger and long-to-boil temperament, wrote an entire treatise about everything that had gone wrong in the translation from the page to the screen.The exceedingly apt title for this biography comes from Algren’s “Chicago: A City on the Make,” published the year after Algren received the National Book Award. He dwells on his love-hate relationship with the city and its grimy underworld, its hustlers, hoaxsters, and losers. “Like loving a woman with a broken nose, you may well find lovelier lovelies. But never a lovely so real.” His prose poem to the city (he’d published many poems to critical acclaim) was written at the height of his cynicism with life, a decades-long attitude, but this book came out during the height of Senator Joseph McCarthy’s Red Scare trials.Some of the most satisfying aspects of Mr. Asher’s carefully researched and beautifully written biography stem from his presentation of Algren’s literary connection with Richard Wright. Although they would have a falling out, Wright was exceedingly grateful to Algren for his thoughtfulness regarding Wright’s groundbreaking novel, “Native Son.” And, of course, there’s the juicy part: Algren’s affair with Simone de Beauvoir. The two could barely speak the same language. Yet they connected on a deep level despite the fact that she was always in a relationship with Jean-Paul Sartre. He took her to demimonde Chicago bars. She took him to Parisian literary salons. During the time she and Algren were together, she completed her extraordinary book “Second Sex.” He’s a character in four of her books.But then there was a detonation. They never spoke again. She most likely burned his letters. Her epistles to him were pulled into a book after his death. In 1975 Algren decided to write about the boxer Rubin (Hurricane) Carter, then in a New Jersey prison for murder, and began interviewing the middleweight, who had been convicted twice. Algren decided he liked Paterson, N.J., where the triple homicide had taken place, enough that he sold most of his belongings in the Windy City and moved there.He made good on his promise to write “The Other Carter,” a novel, and obtained a National Endowment for the Arts grant to keep working on it. His agent shopped it around for a year but was told no by every publisher in New York. Twenty years before, Algren was one of the biggest-selling fiction writers in America. Despite the fact that he’d written for every glossy magazine around — at rates per article much higher than his early novels had commanded — he couldn’t sell the manuscript. Nobody wants a book about a murderer who was convicted twice, Algren was told. Around Christmas 1979, Algren, who’d grown paunchy and lived with a bottle of booze at the ready, had a heart attack. He swore a couple of close friends who visited him in the hospital to secrecy about his health — he’d always been good at compartmentalizing. He soon went back to revising the Carter book. Shortly afterward, in May of 1980, Algren decided it was time to move again. He bought a map of Long Island and rented a cottage in Southampton. He’d never been to the East End before. When his landlady saw the movers drive up with boxes and boxes of books, she threw him out because she was convinced all of those books wouldn’t fit into her cottage. Algren, who was used to finding place after place to stay all his life, went to a pay phone and kept dialing until he reached the playwright Joe Pintauro. The next day Pintauro found him a summer apartment in Sag Harbor, then by August Algren moved into a house on Glover Street, near Upper Sag Harbor Cove, where he liked to swim. His German translator had contacted him, and his Carter novel was being published. Meanwhile, the literary crowd on the East End embraced him: Betty Friedan, Peter Matthiessen, Kurt Vonnegut, E.L. Doctorow, and John Irving. The often irascible Algren had asked Vonnegut to pick up an Award of Merit for the Novel. But when Donald Barthelme nominated him and Malcolm Cowley and Jacques Barzun seconded him for membership into the extraordinarily prestigious American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, Algren changed his mind about snubbing arts organizations. The induction was to be held on May 20, 1981. On May 9 he would throw himself a victory party in Sag Harbor. On May 8, complaining of chest pains, he went to a doctor who recommended he check himself into the hospital. Instead Algren bought everything he needed for his party then took a bike ride through the village. Early the next morning, he went to his second floor bathroom and fell. Dead from a heart attack at 72. His broken watch face read: “6:05.” His last novel, about Hurricane Carter? Renamed “The Devil’s Stocking,” it was published in the United States in 1983. Posthumously. Carter was released on a writ of habeas corpus two years later.Algren is buried in Sag Harbor’s Oakland Cemetery. Linda Ronstadt, Pete Hamill, Gloria Jones, and Kaylie Jones went to his funeral. Writers paying their respects to him at memorial services or otherwise acknowledging his power as a writer included such disparate figures as Studs Terkel, Cormac McCarthy, Gwendolyn Brooks, and many others who spoke about the contradictory elements of a man who was also praised as warm and supportive. His agent, Candida Donadio, selected the epitaph on his grave marker: “The End Is Nothing / The Road Is All.”Lou Ann Walker is the director of the Stony Brook Southampton and Manhattan M.F.A. program in creative writing and literature. She lives in Sag Harbor.