Down in the Corrupted World

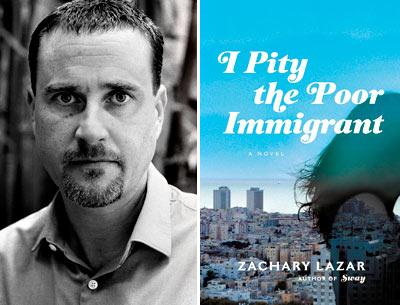

“I Pity the

Poor Immigrant”

Zachary Lazar

Little, Brown, $25

At the very beginning of this intricate and finely wrought novel, its narrator, an American journalist named Hannah Groff, reveals two key elements of the book we’re about to read. The first is that it’s a story of fathers and children. She’s dining with her own father, from whom she’s often estranged, when she makes this observation. And on the next page Hannah, who’s investigating the murder of an Israeli poet, tells us, “What we need is a memoir without a self.”

The reader has not been led astray. “I Pity the Poor Immigrant” is indeed a story of fathers (real and imagined) and their children, and despite the book’s success as a work of fiction, it seems also to reconfigure incidents from the author’s own life, suffused with reflections on Jewish identity and violence in the modern and biblical worlds — becoming a kind of “memoir without a self,” or at least with only a proxy. When Zachary Lazar was 6 years old, his father was gunned down by hit men before he could testify in a criminal trial, an event that Mr. Lazar compellingly addressed in “Evening’s Empire: The Story of My Father’s Murder.” That book — a memoir — reads, oddly enough, somewhat like a novel, with the grittiness of the truth rendered in lyrical prose. Mr. Lazar refers to this portrayal of a father he can barely remember as a “conjuration.”

In “I Pity the Poor Immigrant,” he just as deftly conjures up the notorious mobster Meyer Lansky as he seeks refuge in Israel from American prosecution. Lansky’s story is presented in a collage of actual and fabricated “evidence”: photographs; replicas of official documents and newspaper headlines; direct quotes from other, biographical, books (including a bibliography); the impressions of Lansky’s (fictional) lover, Gila Konig, a death-camp survivor and another “displaced” person, and his own self-justifying rumination on his life in exile: “A Jew has a slim chance in the world.” Gila tries to give him some ordinary human dimension. Viewing Lansky on TV, she remarks that “He looked terrible, weak . . . an old man with a weak chin and a sunken mouth.” And after lovemaking, “His body was not unpleasant. It was a yearning body, and she held him closely in her arms.”

The various characters and events in this novel seem disparate — and even disorienting — at first, as the narrative skips around in time and format and place, and from one point of view to another, but gradually the many facets begin to connect and the central storyline takes shape. Hannah Groff has also known Gila Konig in what now seems like another lifetime, when Gila was Hannah’s Hebrew teacher and her father’s lover. The two women meet again years later after Gila reads an essay by Hannah about David Bellen, the slain Israeli poet.

Hannah tells us: “She introduced me to a Hebrew word then, yored. Its root means ‘to descend.’ It’s what Israelis are called when they leave and go to another country. They have ‘descended.’ They have gone down to the corrupt world outside, so to speak, abandoned the holy land that is their rightful home.” Gila also shows Hannah photographs of an apartment in Tel Aviv, a gift to her from Meyer Lansky that she’s converted into the currency she needed to migrate to the United States, to become yored. The abandoned apartment, too, becomes an integral part of the larger picture, a clue in the mysterious murder Hannah is investigating.

The promise that this will be a tale of fathers and children is more than fulfilled. Hannah’s precarious attachment to her father, Lawrence Groff, is complicated by his relationship with Gila, which may have begun before or after Hannah’s mother’s death, although he’s promised his daughter complete transparency. “I tell you everything. That’s the rule.” In David Bellen’s writings, he offers a moving appraisal of the frayed bond between himself and his addict son, who refuses to see him. “I don’t think my son Eliav even wants the power he has over me — he just has it.”

And Meyer Lansky is seen most vividly in his unfeeling treatment of his severely disabled son, Buddy. “I wanted you to have a good life,” Lansky tells him. “I’ve always wanted that more than anything else. But I can’t keep taking care of you like this. You’re too old for it,” while Buddy daydreams about being wheeled off a bridge or the roof of a motel. Even the biblical David is seen in a new light, vis-a-vis his parenthood. As Hannah puts it, “Before long, the beautiful Absalom will be leading a popular uprising against his father, who no longer looks like the boy with a slingshot but more like the monster Goliath.”

David Bellen’s mutilated body was found in a vacant lot in a village just outside Bethlehem, where there’d been a recent expansion of Jewish settlements, and some of Bellen’s poems in his collection “Kid Bethlehem” were critical of Israeli policy in the occupied territories. But the initial statement made by the Israeli Defense Forces was that the murder was “likely an act of terrorism,” and then the escalating war with Hamas distracted them from further inquiry.

In search of the truth about Bellen’s death, Hannah travels to Jerusalem to meet with an Israeli journalist named Oded Voss, who’d covered the murder until he ran out of information and public interest in the case. En route, she allows that she’s never cared much about Israel: “. . . my lack of interest was so longstanding that perhaps I should have wondered more about it. On a deeper level, I might have realized, I had never wanted to face too directly the idea of myself as a Jew.” The El Al people keep reminding her, though, wondering why someone with a Hebrew name has never been to Israel before. “They were smiling as they said it, but it was precisely this kind of righteous shaming that I had always taken pains to avoid.”

Voss accompanies Hannah on her quest, and in the process becomes her guide to Israeli politics and history as well as her lover. They visit Bellen’s son, Eliav, now a shopkeeper of kitschy, Jewish-themed art, who submits his own enigmatic take on the murder. “My father was attuned to the violence inside people.” In the working-class neighborhood where David Bellen grew up, a boyhood friend ventures that Bellen, at 65, was still “like a child.” “Writing nonsense about this world he knew nothing about. Only a child would do something like that.” Finally, Hannah receives an anonymous email that speculates Bellen may have killed himself, echoing something Voss had said and that she’d dismissed as “some kind of aburdist joke.”

In “Aspects of the Novel,” E.M. Forster brilliantly notes that “ ‘The king died and then the queen died’ is a story. ‘The king died, and then the queen died of grief’ is a plot.” Zachary Lazar has given us both story and plot, the solution to a gangland-style killing and all of its far-reaching emotional ramifications. As he did for his memoir, Mr. Lazar borrows the title of this book from a Bob Dylan song. Everyone in the novel is an immigrant (or yored) of one sort or another, attempting to escape from global or personal history — as Hannah’s father says, “The past was what you were trying to get away from” — and they are all depicted with a measure of sympathy, if not outright pity.

A variety of crimes are recalled in “I Pity the Poor Immigrant” — from the white-collar offense of fraud, to grisly underworld slayings, to the ultimate atrocity of the Holocaust. Hannah concludes that “Perhaps the reason I have never wanted to face too directly the idea of myself as a Jew is that all roads seem to lead to the Holocaust Memorial, as if it is the Holocaust that makes one a Jew.”

Like his fictional female counterpart, Zachary Lazar is “a crime writer with a fractured style.” He’s also a true conjurer, a magical writer who offers fresh and disquieting insights into the world we thought we knew.

Hilma Wolitzer’s most recent novels are “An Available Man” and “Summer Reading.” She lived part time in Springs for many years.

Zachary Lazar, whose previous novels include “Sway,” teaches in the English department at Tulane University. He has a house in North Sea.