Draw Swords Over Lighthouse Armor: Some say shore it up; others, move it inshore to protect favorite surf spot

If the bluff at the Montauk Lighthouse is not armored with an expanded rock revetment, the landmark could topple into the sea in 8 to 10 years, representatives of the United States Army Corps of Engineers said at a hearing on the project on Monday.

If the bluff at the Montauk Lighthouse is further protected by a bigger revetment, two of the East Coast's "premier" surf spots, Alamo and Turtle Cove, could be ruined, said members of the East End chapter of the Surfrider Foundation at the same hearing.

And so it went at a two-hour session of public commentary at the Montauk Firehouse that was held to discuss a draft environmental impact study released by the corps on Aug. 19. Copies of the study are available at the Montauk and East Hampton Libraries.

The Army Corps proposes an 840-foot-long stone revetment, which would be 40 feet wide at the top. Some 12.6 tons of stone would be embedded in the bluff to protect it from breaking waves and to provide long-term stability. The cost, which is expected to be split among federal, state, and local government, would be about $14 million for the project.

The work is badly needed, said Greg Donohue, the erosion control manager at the Lighthouse. On Monday he said that the "necklace" of rocks now lining the bluff is shifting. The "faulty foundation" there will eventually breach, he said.

"We have headaches there. The revetment is coming apart right before our eyes," he said, producing photographs as evidence.

Tom Pfeiffer of the Army Corps summarized the proposed project for an audience of about 125 people, including East Hampton Town Supervisor Bill McGintee and the superintendent of the Montauk state park complex, Tom Dess. He said that the corps had considered other plans, but found no other one that would offer long-term protection.

Considering its fragile state, moving the 200-year-old Lighthouse to the back of the property, as some surfers have suggested, would cost too much and be all but impossible, Mr. Pfeiffer said. Every part of the Lighthouse would have to be documented the way it is now, and it would have to be moved brick by brick, Mr. Pfeiffer said, adding, "It would never be the same."

Larry Penny, the town's director of natural resources, who is running for a seat on the town board, said he had studied the proposal and that "we're in trouble if we don't build on that rock."

"Like me, the structure is aging and frail and would not survive a move," he said, calling the Lighthouse Long Island's most historical feature.

The project will not harm wildlife and vegetation; "you're not going to muck up our natural resources," he told the engineers.

Some, however, disagreed that the Lighthouse could not be moved. Lighthouses on Block Island and at Cape Hatteras, N.C., have been moved, they said.

"The technology is there," said Tom Muse, the environmental director and spokesperson for the Surfrider Foundation. Mr. Muse said the corps had not supplied enough information about the armoring project and wondered if the revetment might do more harm than good.

"Are we going to be looking at Montauk Lighthouse Island after the revetment?" he asked. "It will not look like your little document there," he said.

Using a "hard" erosion-control device would set a bad precedent, Mr. Muse said, adding, "You have a lot of well-heeled people out here who will want to do the same thing to protect their property."

He asked the engineers to come up with a plan to save the Lighthouse without changing the way the waves move.

In the report, the engineers said the project would have very little impact. Chris Ricciardi, the study coordinator, said at the meeting that Montauk Point State Park and the Lighthouse could stay open while the revetment was being built, which would most likely start in 2008 and take at least two years.

There is no way not to have any impact at all over the course of a construction project, he said, and "once they go into the water there will be a short-term impact."

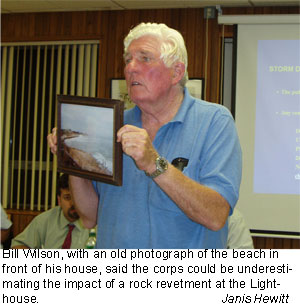

Two Soundview Drive homeowners took issue with that assertion. Herbert McKay and Bill Wilson told the audience that many years ago the Army Corps sat in the same place and told them that extending the jetties at Montauk Harbor east of their houses would do little harm to the shoreline there.

"And now we have no beach," said Mr. McKay.

Soundview Drive property owners have claimed that when the Army Corps of Engineers tightened and extended the jetties in the early 1970s it interrupted the natural flow of sand and starved their beaches. Most have built bulkheads there now.

"There were 40 families on that beach and you sat here and told us there would be no impact. You unsettled that whole community. And look what you're doing now; you are giving us misleading information. There will be a long-term impact. I'm going to predict that," Mr. McKay said.

Mr. Wilson brought photographs showing the beach he used to have but had lost.

"These engineers are despicable. I think it's time we all jumped on their bones. They talk about terrorists; they're the terrorists," he said, sweeping his arm toward the panel.

The comments and questions that arose at the meeting will be addressed in the final environmental impact statement.