Dream of New Life For Sherrill Farm

In 1792, Abraham Sherrill bought a farm at the foot of Fireplace Road in East Hampton, where it meets North Main Street, “to move out of town where it’s quiet,” according to one of his descendants, Jonathan Foster, who still lives there.

The house, which is on the National Register of Historic Places, was made over in 1858 in a late Greek Revival style, but elements dating from 1760 or earlier remain.

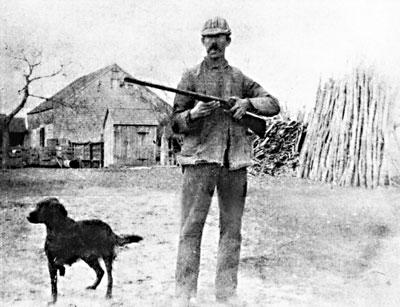

In 1910, A.E. Sherrill founded the Sherrill Dairy at the family farm, which once extended all along North Main Street’s east side from Cedar Street to what is now Floyd Street.

With some of the original farmland still intact — acreage that remains in the Sherrill family, as well as 16 adjacent acres that the town has preserved by buying the development rights — a committee advocating for the site’s public purchase using East Hampton Town’s community preservation fund sees it as the perfect place for a historical institute melding the agricultural past with modern-day farming and providing a place for students of history to soak in the past.

The group includes members of several of East Hampton’s founding families — Sherrills, Daytons, Fosters, and Talmages — along with historians and active farmers.

To generate interest in their idea, they have invited visitors to an open house on Friday, April 6, at 3 p.m. East Hampton Town Board members have specifically been invited in hopes that they will move to buy the site.

“The family, the house, the dairy . . . all the things that transpired on that property. I just can’t imagine not fighting for that house,” said Prudence Carabine, an East Hamptoner of Talmage lineage who has twice gone to the town board to ask that members consider preserving the house and land. “To me, it’s worth keeping intact,” Ms. Carabine said Tuesday.

A member also of a committee working to create a farm museum on the former Lester (and later Labrozzi) farm at the corner of North Main and Cedar Streets nearby, which the town bought with the preservation fund, Ms. Carabine said she pictures rooms on the upper floors of the Sherrill house occupied by visiting researchers and scholars and an active farming operation, perhaps incorporating the newest organic methods with traditional techniques, on the land out back.

A small house on a separate lot next to the one holding the historic house, which was built by the late Sherrill Foster, the great-great-great-granddaughter of the property’s original owner, would be donated to the town by her heirs, Mr. Foster and his sister, Mary Foster Morgan, and could be used by a “young farmer,” Ms. Carabine said, charged with caring for the historic house and gardens and helping organize community events, like pumpkin picking.

While the Lester site farm museum down the street will exemplify the living quarters and lifestyle of a typical farming family circa 1810, the Sherrill house could serve as an example of “a farmhouse of some prosperity” circa 1850, Ms. Carabine said. “People could actually come in the front door and feel they were in the 1850s, prior to the Civil War.”

Together, Ms. Carabine said, the two facilities could “make North Main Street a focal point,” portraying “the farmers and the fishermen who kept this place going.” It would provide “a sense of East Hampton’s early look and feel,” Mr. Foster wrote yesterday in an e-mail.

Maintaining an open vista, Mr. Foster wrote — the view across plains to the ocean that produced “that magical light which drew out the artists in the 19th century” — in an area where trees have grown up over the years, will help preserve “that sense of grandeur and closeness to our natural-historical world.”

Over the years, the Sherrills have carefully preserved history, maintaining records such as a list tracing the ownership and occupants of the house and its changes over time, such as the installation of a “modern” kitchen in 1927, which had an enamel sink and a breakfast nook with an Arts and Crafts table and a Hoosier cabinet.

The Sherrills bought much of their furniture from the Dominys, who lived and worked on the other side of North Main Street, and items such as cabinets, a railing, and a mantel remain in the house.

From the 1760s to the 1840s, three generations of Dominys made furniture and clocks that earned the family a widespread reputation, and a room is dedicated to the East Hampton furniture-makers at the Winterthur Museum in Delaware. The Sherrill collection of Dominy furniture was prominently featured in “With Hammer in Hand,” a book by Charles Hummel, a former Winterthur curator.

Now at a busy intersection and built close to the road, as was common in days past, Ms. Carabine said she fears the Sherrill house would have little appeal to a potential buyer, and would be torn down. Though inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places precludes changes that could compromise a property’s historic integrity, it does not prevent demolition, she said.

Mr. Foster has completed a careful renovation of the house. It is in good shape, Ms. Carabine said. “We have a plan for fund-raising, for carrying this whole thing forward without any burden to the town,” she said.

The house, in its present configuration, was renovated for Nathaniel Huntting Sherrill by Charles A. Glover of Sag Harbor, with the help of Stephen Sherrill, at a cost of $1,560. Mr. Huntting Sherrill was married in 1859 and lived in the house at the time with his wife, 21-year old Adelia Anna Sherrill, his parents, and three brothers.

Sherrill Foster was born in the house and was an East Hampton Town historian for many years. She traced her roots to 30 of the 47 East Hampton families included in Jeannette Edwards Rattray’s 1953 genealogy of East Hampton.

In 1992, descendants from those founding families came from near and far to commemorate the 200th anniversary of Lt. Abraham Sherrill’s purchase of the land. The 1792 deed is among the documents preserved and displayed by the family.

Ms. Foster spent several years organizing the event, which included “Maidstone Revisited,” a two-day lecture series at Southampton College by history experts.

Shortly afterward, the house and the acre it sits on were listed for sale for $600,000 and the idea of having the town buy the site for preservation was first broached. According to an article in The Star, Tony Bullock, the town supervisor at the time, said federal and state funds for preservation were largely unavailable, and that the town had a financial deficit. Those advocating for public preservation at that time noted that the Dominy family house and workshop had been lost — although the Winterthur recreated the workshop and bought many of the family’s tools and molds.

In 1995, the town bought the development rights to 16 acres of the original Sherrill farm, which was owned by Thomas Martuscello, paying $560,000 to maintain its use for agriculture. There was talk of putting a winery on the site, and some of the acreage has been planted in grapevines.

According to Town Councilman Dominick Stanzione, who until recently was the town board’s liaison to the community preservation fund committee, the historic house and land is on the list of properties eligible for acquisition. Whether the committee has evaluated the site and rated it against other potential purchases is “confidential,” he said.

At present, the town’s preservation fund, which receives the proceeds from a real estate transfer tax, and is earmarked exclusively for open space, farmland, and historic preservation, has about $23 million available for purchases, Scott Wilson, the director of land acquisition and management, said Tuesday.