In the Dry Months

Here I am, an old man in a dry month,

Being read to by a boy, waiting for rain.

— from “Gerontion” by T.S. Eliot

While it is a truth that anyone who lives to old age will experience inevitable deterioration, the facts of each case go universally unacknowledged. The personal reality of decline is hard to express, takes time away from life itself, and conflicts with the abundance narrative — youth, marriage, sex, and childbirth are more celebrated. Who wants to dwell on death?

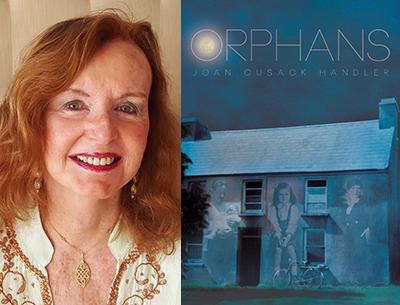

“Orphans” (CavanKerry Press, $18) is a verse memoir about just that. It is a story told in poetry with a combination of quiet daring and mundane development. The book consists of crisp free verse elevated to the heights of prosaic narrative, but the details are of particular significance. It’s about what it means to lose a mother and a father, and how those losses foreshadow others. If our parents can die, then anyone can.

T.S. Eliot wrote about “The notion of some infinitely gentle / Infinitely suffering thing.” Joan Cusack Handler has as well, yet her account of the thing contains a specificity Eliot barely intimated. “Orphans” is divided into equally poignant halves. The first is about the life and times of the poet’s mother, Mary O’Connor Cusack, and consists of more numerous, shorter pieces. The second is about the poet’s father, Eugene Cusack, and made up of fewer, more lengthy pieces. Ms. Handler is honestly fearless in these exploratory memorials to her parents.

The theme of “Orphans” turns something rather rare into something very familiar. While you may not have been born an orphan, you will most likely become one. The double fortune of having parents turns into a double grief when they pass. It’s terrible and ordinary all at once.

One by one, we came,

each emerging from her dark appraisal — for there was

nothing of that harsh branding now. All guile gone —

abundant words of each one’s worth.

It took till she was dying

for her to know we loved her.

This is from the fifth section of a long poem titled “Inoperable.” It’s especially touching as the poet’s mother is the suffering type to begin with. Her personality gets undermined by self-doubt to the degree that she victimizes her own family. Their genuine desire to support her in a time of great adversity is thrown back. The poet reveals the truth of the matter, while struggling to come to grips with her mother’s painful experience.

The poet identifies with her mother, and the writing is dramatic, yet tensionless. It’s daunting to care for the terminally ill, let alone put it into words. Ms. Handler’s poems are often composed in concrete forms. Concrete poetry shapes words on the page into images of recognizable things. While some poets make exact resemblances, such as a poem about pyramids shaped like a pyramid, “Orphans” depicts angelic forms dancing page to page. The poems turn and twist, gyrate and drill into the earth as they rise. The use of concrete forms here is striking, almost violent in a gentle manner.

While “Orphans” does much to further a compassionate narrative toward the old and the dying, it falters in literary achievement. The challenge of emulating a prose memoir is that the story needs movement. The progression from poem to poem here achieves intimacy, but sacrifices lyrical expression while fruitlessly reaching for epic structure. There is little redemption beyond the page. Still, the endeavor is praiseworthy for keeping it real.

Help me find a way to

like her. We deserve it.

I want to respect her.

I want to be able to hold her

when she needs me to. I want to

look into her eyes when she is dying.

I want to give her that.

I want not to look away.

This is from “Lately,” a piece about the failing health of the poet’s mother. It’s an incredibly personal example of the journalistic narrative in “Orphans.” Many reminiscences in the book are successfully infused with voiced interjections by her parents themselves, as if their commentary were never far from mind. Ms. Handler’s account is sporadic and tends toward the anecdotal. However, it gathers force and cohesion toward the second half of the book, which details her father’s demise.

It happened when we got the diagnosis.

Resentment suddenly gone;

only love left — each of us standing in line.

This passage is also from “Inoperable” and portends what we realize is inexpressible. The merit of the work is manifold. With procedural courage, the poetry faces a kaleidoscope of pain while staring at the scars of emotional truth. If language is a running commentary on our broken-down story, who doesn’t want it to pulse with new life?

The second half of “Orphans” is most notable. It is at once laconic, conversational, and rambling, yet empathetic to generational decay. No one is exempt from the conflict. Absence affects us in ways we cannot comprehend. Accidents and injuries dictate our existence in the end. Most of us would like to forget, or at least move on from, the collective fear of death. But here we remember our mother and father.

When did it happen

that the future started

to darken,

shrink,

pick up speed in that

final sprint that will wipe out all

love from my life?

(A passage from the penultimate piece in the collection, “The Poem.”)

Lucas Hunt is the author of the poetry collections “Lives,” “Light on the Concrete,” and “Iowa,” which is forthcoming. Formerly of Springs, he is the director of Orchard Literary and the founder of Hunt & Light, a publisher of poetry.

Joan Cusack Handler’s books include “Confessions of Joan the Tall,” a memoir. She lives in East Hampton and New Jersey.