Eclectic Work Inspired by Nature

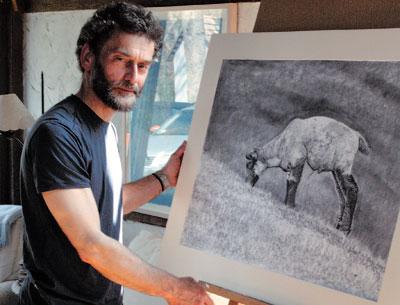

Toby Haynes is a representational artist whose work ranges from portraits of animals to portraits of people and to seascapes and plein-air landscapes. A man who divides his time between East Hampton and Launceston, Cornwall — where he has lived since 1978 with sheep and cows grazing outside his window and, for 17 years, without electricity — it is not surprising that he is inspired by nature and by the light in both places, which are surrounded by water. He moves easily among the traditional mediums, pen and ink, pastel, oil, acrylic, charcoal, pencil, and watercolor, and he sometimes mixes them.

“The rot set in in the 19th century,” he said recently, discussing the estrangement of painters from their materials, “since the 1830s, when they invented the collapsible tube.”

“Before that a painter would have made his own brushes and his own paints and would have first been an apprentice, doing the dirty job, making lead white (flake white), for example, which involved putting zinc plate over cow dung (for the heat) and leaving it in a shed for months and then collecting the lead in flakes.”

Mr. Haynes didn’t develop a real interest in making art until finishing his university schooling. He started in watercolor and pastel, working on hard paper. Much as a Florentine artist would make detailed drawings for frescos, he said, he relies on preparatory drawings to minimize mistakes in watercolor, which he finds particularly challenging for his hyper-realist style. But he doesn’t want his work pigeonholed. “I rather prefer not being automatically identifiable; I don’t think it’s healthy. A variety of styles and techniques and mediums can only be good,” he said.

“Pastels taught me to work with clean color. My oil painting has benefited from using them. Using pastels, it’s best to work with colored paper that has watercolor stained on it and then pastel over that.” He often stains his canvases that way, letting them dry before beginning the actual picture. Most recently, he has been using paints made by Vasari, a New Jersey company that grinds paint by hand and produces pure colors.

He explained that he had used “student colors,” lower price paints that contain additives and fillers, but discovered he could not mix the shade he wanted. He now uses student colors to prime palettes. “That’s about all they’re good for,” he said. “I would advise young painters to use good materials, although the price differential can be extreme.”

Having no electricity for 17 years was “interesting for the rhythm of the seasons and the quality of light,” he said, but it limited the amount of time he could paint, which also affected the colors he chose. “By oil lamp the colors came correct,” he said. “When it’s very cloudy, the gray intensifies the yellows and greens. . . . An oil lamp is yellower than electric light,” he said, adding that, with electricity, it is better to use daylight-balanced bulbs rather than those that seem blue.

His collectors have remarked on his ability to capture the personality of his subjects, without anthropomorphizing them. The titles he chooses have a light touch, such as a watercolor called “Herd About a Cow” or, for one in which a cow looks as if she is about to touch her nose to the camera lens, “I’m Ready for My Close-up, Mr. DeMille.”

“I always liked painting animals. I like anything where draftsmanship helps. Maybe being the son of a craftsman, I appreciate the craftsmanship element of it. And, with animals, it’s always nice to make people look more closely at them, especially farm animals. Anything is better if you stop and absorb it.” He did a drawing of a cat he had for many years using 20 grades of pencil, he said, from 9H, the hardest, to 9B, the softest and darkest. “One would almost never use the full 20 in one drawing, but Willow deserved them all,” he said.

It is not just animals that draw the eye to his work, but even rocks, water, and sand, especially in pictures of Gerard Drive or Accabonac Harbor in Springs, which have a play of sunlight and shadow.

Christened Richard John Haynes but called Toby as an adult, Mr. Haynes uses the initial T when he signs his work as RJTH. He grew up the youngest of three in Essex, 40 miles from London.

“We were always encouraged by our parents, given boxes of paint at Christmas, that sort of thing.” His father, a sign painter, was “a bit of a frustrated artist,” he said. “My mother would have liked me to have a regular job, because my father didn’t. He was self-employed.”

He read philosophy and German at Oxford, and worked part time for the National Trust for three years, moving footpaths, building bridges, and tending 1,000-year-old hedgerows. He called the work “Robinson Crusoe-type carpentry.” He continued to freelance for the trust and for other organizations for another five years, painting in his downtime until it took over.

Since coming here first in spring 2010, Mr. Haynes has been in several group shows, including at the Pamela Williams Gallery in Amagansett in 2011, the first year he exhibited his work in this country, the Water Mill Museum, Ashawagh Hall, and Guild Hall. In the spring of last year he was awarded a prize at the juried East End Arts Council “East End Light” show for a large pastel study, “Evening Light, Gerard Drive II.” In the E.E.A.C. show on now until June 1, he has a painting, “Death of a House.” His “Amagansett Shed” will be in a show in that hamlet scheduled for August. An oil painting of a cow, “Maybelline,” was shown at the Southampton Cultural Center last fall. He has also won awards in Cornwall.

Mr. Haynes said he particularly admires Jan Vermeer, the 17th-century Dutch painter, and is able to find abstraction in his meticulous interiors. “All art, even the most fastidiously realistic work by the surest classical technician, involves abstraction: In seeking ways to convey texture, light, mood, three-dimensional form, etc., one inevitably selects, alters, omits, and adds all manner of material, deliberately or unwittingly. . . . It’s impossible to paint a picture of nothing. We are all somewhere along the line that doesn’t separate, but connects, the two extremes.”