On the Edge of Normal

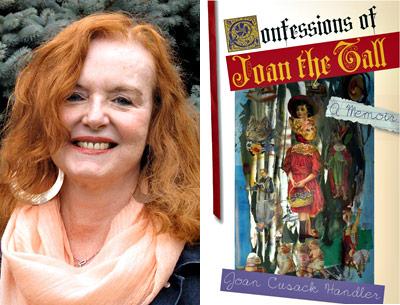

“Confessions of

Joan the Tall”

Joan Cusack Handler

CavanKerry Press, $21

Ah, growing up — there’s no escaping it. In Joan Cusack Handler’s quasi-anthropological memoir, “Confessions of Joan the Tall,” the author relives the indignity of classroom students everywhere who have been subjected to a public weighing and measuring. In milliseconds, these students are banished to the Land of the Less Than Perfect — too slight, too heavy, too short, too tall. While the average height for an 11-year-old girl is around 5-foot-2, Joan towered in at 5 feet 11 and one half inches, on the outer edge of the normal scale. Giant, freak, beanstalk, nicknames all, she vows she will never be a circus freak, no matter what.

In parochial schools, students, girls, for the most part, plugging for a better grade would write JMJ on their papers, homework, and exams, usually in the upper-right-hand corner. The nun-pleasing abbreviation stood for Jesus, Mary, and Joseph, which is centered on the top of each page of “Confessions of Joan the Tall.” A good student, Joan is summoned to her older brother’s class where his nun, a member, ironically, of the order of the Sisters of Divine Compassion, grills her on the multiplication tables, which she aces, an exercise that can only serve to humiliate her brother Sonny in his struggles to master “rithmetic.”

Beset by “nerves” and the “freakishness” of her height, Joan, in spite of her litany of impassioned prayers, “pees” often — in her sixth-grade classroom, on her mother’s bed — and is a nightly bed wetter. Mary Cusack, the oft-angry yet commercially perfect housewife, insists Joan, by now a seventh grader, wash the sheets in the bathtub each morning, hoping this malodorous chore might put an end to the nightly bed-wetting. When they turn to a specialist with, according to Joan, a body shaped like a Humpty Dumpty, tiny feet and all, he tells her mother who tells her father that the doctor has called her a “dirty pig.” So much for a professional opinion. (The author mentions pee so often in her memoir it seems as if she should have considered the title “Confessions of Joan the Wet and Tall.”)

Self-identifying as her mother’s favorite, Joan alone avoids her mother’s belt-strapping tirades because Joan’s bodily shaking — nerves again — so confounds her mother. When her mother, pushed to the edge, does beat her, overcoming her fear of her daughter’s suffering a nervous breakdown, Joan is relieved that her siblings may no longer think of her as the favorite. But Joan and her mother’s shopping trips, on which the sales help and her mother compare “tall Joan” to runway fashion models, and Joan’s shopping bag of purchases, can only serve to confirm her “favorite child” status. (The $22 dollar bathing suit, purchased for her by her mother in the mid-’50s, would run around $188 in today’s dollars, a stretch for not only this working-class family but also most others.)

The Catholic religion, or, at least, Joan’s scrupulous interpretation of its principles, has to contribute to her nervous condition. She wrestles with her every thought, every judgment, weighing whether behaviors of her own and the Cusack family members merit a venial or mortal sin. Berating herself for her unwillingness to enter a “regular” religious order, much less the cloistered order of the Poor Clares, she drags the reader through the blacks and whites of her thought processes. The endless repetitions of her moral judgments, always through the veil of Catholic theology, become wearisome.

“I would be so happy if they were Americans,” Ms. Handler, a poet, writes, confessing her shame of her Irish immigrant parents. The way that they and she pronounce the letter H (haytch), her mother’s penmanship and spelling on school notes, and, especially, her mother’s unwillingness to participate in the Rosary Sodality, the church’s women’s social group, embarrass her.

Her father, a hard-working, take-any-job-he-can-get plumber, is the far more religious and social of her parents, although she would prefer he carried a briefcase to work; her admiration of him, bordering on worship, coupled with her need to please him may help explain her near religious fanaticism. Her mother’s self-imposed isolation sparks Joan and her younger brother, Jerry, to fantasize what it would be like if their mother had friends and ventured out of the house.

While the Cusack family may be a stereotype, with their nightly rosaries and their frequent attendance at Masses — “the family that prays together stays together” — they do gratefully break that implacable Irish hard-drinking stereotype. Since drunkenness is considered almost a mortal sin by the Cusack family, Eugene’s one-time slip at an after-work Christmas party infuriates his understandably shrewish wife, who threatens to “not have Christmas.” Worse yet, he drank during the holy season of Advent, as his daughter recounts.

Sonny, who revels in punching out his younger siblings, defends his father’s drinking and tells Joan that their dad used to steal pocket change from his older brother in the old country. Rather than accept her father’s flaws, Joan concludes that Sonny, with his penchant for violence, is also a “big, fat liar.” Her fear of Sonny’s retributions and unexpected outbursts adds to Joan’s already recognizable case of nerves.

The chronological skipping, coupled with the brevity of the chapters — four pages would be a long chapter — along with the roughly hundred or so chapters in the memoir, makes following what stage Joan is in difficult. To a reader, it may cramp any forward-motion narrative drive. And since the pre-adolescent/adolescent voice is carried throughout the memoir, I found myself asking how old is Joan now, grateful for any indication of her age and/or grade, and admit that often I didn’t care enough to go back and reread.

Edgewater Park, on the southeastern edge of the Bronx, borders Long Island Sound, whose waters appeal to tall Joan, who could safely disguise her height in the forgiving Sound. Jerry, the youngest Cusack, with his beautiful voice sings “Danny Boy” or that fun staple “Who Put the Overalls in Mrs. Murphy’s Chowder?” at get-togethers in the neighborhood. The Edgewater Fife and Drum Corps, or a variation thereof, of which Joan was a proud member, still performs; idyllic holidays with a swim in the Sound were and are still a revered part of this community.

When, at last, Joan struts down the Edgewater bulkhead in her expensive white bathing suit with its padded bra, she notices that the older men in the neighborhood turn to ogle her. And their interest makes her begin to believe that her adulthood and her height, her tallness, will bring her a different life, a happy life.

Carole O’Malley Gaunt is the author of “Hungry Hill,” a memoir of growing up in an Irish-Catholic family in Springfield, Mass. She lives part time in Sag Harbor.

Joan Cusack Handler is the author of the poetry collections “Glorious” and “The Red Canoe: Love in Its Making.” She lives in Fort Lee, N.J., and East Hampton.