Elusive Love

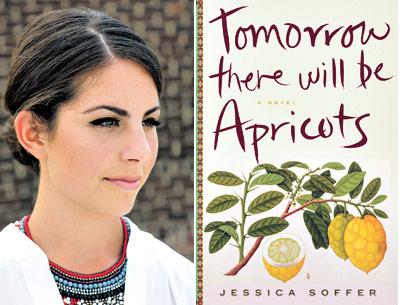

“Tomorrow There

Will Be Apricots”

Jessica Soffer

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, $24

Very little in this book is what I expected it to be.

“Tomorrow There Will Be Apricots” the handwriting jauntily promises over a striking early-19th-century botanical illustration of craggy, medieval-seeming lemons hanging off a branch. A quick flip through the pages reveals French and Arabic food names (samoon, shakrlama, bamia, malfuf, poulet roti, chocolat chaud) that, together with the blurbs and the inside cover, signal to me that the book will be full of sensual food experiences shaping the lives of Jewish-Middle Eastern (the word for apricot is “mishmash” in both Hebrew and Arabic) foodie immigrants in New York City.

Since the father of Jessica Soffer, the author, came from Baghdad and I know that Soffer is a Jewish name, I settled into the first pages of “Tomorrow There Will Be Apricots” with my expectations populated by “Like Water for Chocolate,” “Eat, Pray, Love,” and multicolored memories of a life of Asian, Middle Eastern, and Jewish feasts.

Not quite! Jessica Soffer’s story is about food but it’s not about eating. Food metaphors abound (“eyes gray and blue like the healthiest sardine pulled straight from the ocean,” “a lump in my throat the size of a bundt cake pan,” “tall and thin like a saffron thread,” hair “shiny like swirled chocolate butter sauce”); she threads the book with names, ingredients, and preparation steps, but they don’t bring with them the joy of cooking, the sensuality of eating, or the conviviality of a shared meal. Instead, the characters turn to food and its tentacles (talking, teaching, scheming, books, recipes) to connect them to those whose love they desperately seek. It’s in restaurants, rather than at home in the kitchen or dining room, where significant encounters occur and relationships take root.

For Lorca, the 14-year-old girl who comes of age in the book, the recipe for masgouf, an Iraqi fish dish, becomes the Holy Grail that she hopes will secure her mother’s ambiguous love (“she loved me in fits and spurts”) and prevent her from being sent off to boarding school. The quest leads her to the widow Victoria, owner of a now-defunct restaurant where Nancy, Lorca’s mother, herself a famous restaurateur, had once tasted the elusive masgouf.

Ms. Soffer adeptly plays with our assumptions about inherited traits and family resemblances — we think we know where the story’s going until she reveals the truth, dismantling what we thought we knew. She holds back the revelations until we know the characters well enough to be startled by what they’ve been hiding. Once or twice I wished she had waited longer to expose the truth, I could have gone along for a longer ride, but maybe the author herself felt the hiding was unbearable, that she herself was unable to contain it any longer.

“Tomorrow There Will Be Apricots” is a lively book, structured on revelations within complex relationships that weave smoothly between the past and present, but it is anything but jaunty. At the heart of the story is an underlying darkness, amplified by the background of unrelenting New York City winter. This is a story about waiting — waiting for love, for approval, for the arrival of a sister, a daughter, a granddaughter, for the bell to ring or the door to open, for redemption to replace abandonment.

Despite the enormity of the secrets — betrayal, self-mutilation, affairs, lies of omission and commission — we do not judge these secret-keepers: We see them as weak rather than evil, motivated by fear rather than cruelty. Desperate for connection, they imagine rather than actually have conversations, ascribing thoughts to each other because the potential pain of actual encounters would be unbearable. As a result, connections are not established and relationships remain fragmentary and unresolved.

All this against a background of food! If only, I wanted to say to Lorca or Victoria or Nancy, if only you would actually sit and eat together, if only you could taste how delicious the chocolat chaud or the bamia or the pasta arrabiata actually is, perhaps you won’t have to be as confused as Lorca is when she offers her friend Bolt a dish of bamia: “It was clear he didn’t not like it.” If only you could be as attentive to the people in your family as you were to the diners in your restaurant, I wanted to say to Lorca’s mother and Victoria.

But what I wanted most of all was to understand the darkest secret of all — why Lorca is addicted to cutting herself. Perhaps cutting is prevalent enough in our society today and other readers know more about the psychology of self-mutilation than I do: I had no idea that behind the jaunty cover and the beautiful illustration of lemons lies a bleak story of a teenager who turns a paring knife, a small kitchen implement used for peeling and coring, against herself. A paring knife of all things!

Ms. Soffer provides only a superficial understanding of why young girls resort to cutting themselves, but we witness Lorca’s struggle with the “itch” imperative to cut herself, the gratification of seeing the blood emerge, the shame of being discovered, and the punishment of being dispatched to boarding school.

There were times that I wished the author had been given to a more patient exploration, yet it is Lorca’s story that I am left with, her poignant attempts to connect to her equally damaged, mercurial mother as she turns for comfort to the elderly Victoria, herself unmoored by death and truth. Although I am the first to mock our culture for its excessive “oversharing,” this book reveals how much may lie hidden in the stories we are too afraid to share — or to hear.

Hazel Kahan lives in Mattituck, hosts two radio programs on WPKN, and writes about growing up in Pakistan. Her Web site is hazelkahan.com.

Jessica Soffer teaches fiction at Connecticut College. She lives in New York City and Amagansett, where her father, the late Sasson Soffer, was a sculptor.