End of the Idyll

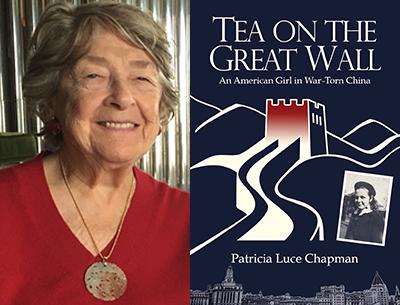

“Tea on the Great Wall”

Patricia Luce Chapman

Earnshaw Books, $19.95

Nearly 30 years ago, I donated a collection of family letters from the World War I period to the New York Public Library. In her acknowledgment letter, the head of the library’s manuscripts department stated the importance of having “records of the lives of ordinary people in extraordinary times.” I was constantly reminded of that admirable turn of phrase as I read Patricia Luce Chapman’s thoroughly charming memoir, “Tea on the Great Wall: An American Girl in War-Torn China.”

Just when I had begun to think there had been too many memoirs published in recent years — this reader was certainly “memoired out” — along comes Ms. Chapman to restore my faith in the genre and demonstrate that, in the correct hands, it can remain fresh and uplifting.

Essentially, Ms. Chapman’s book covers the years between 1932 and 1940 (when she was 5 to 13 years of age). Her American parents, John S. Potter and Edna Lee Booker Potter (a highly regarded businessman and a pioneering female war correspondent and author), had each come to Shanghai during the second decade of the 20th century, in search of adventure. After they married, they established a comfortable home in the genteel, sophisticated International Settlement section of the city. Their children — John Jr. and Patty — were raised in what must be described as a loving and luxurious household. It was a life of good manners, elegant parties (for parents and children alike), multiple servants, and posh travel.

Ms. Chapman’s account gives ready lie to the notion that happy families are all alike (and therefore uninteresting), as well as to the idea that a privileged upbringing inevitably leads to selfishness and laziness. In spite of her elevated circumstances, Patty develops an almost precocious sensitivity to the hardships of others. As a child she witnesses the unspeakable suffering of opium-addicted coolies pulling rickshaws in the Shanghai streets, and this creates an indelible impression (for the reader, too).

Beginning when she is 5, the harsh realities of the world at large slowly intrude on Patty’s cosseted existence. By the time the Potters reluctantly leave China for good, they endure two invasions by the Japanese and the escalating brutality of the invaders, largely toward the Chinese themselves. “It is a terrible thing for a people when an enemy settles over the land,” Ms. Chapman’s mother writes in 1940.

Moreover, soon after Patty is enrolled in the private German School, the beloved headmaster and several teachers are summarily replaced, in favor of ardent Nazis, under orders from Berlin. Like others throughout the world, Patty and her family slowly come to the realization of what National Socialism is really about.

The first Japanese invasion, in 1932, begins with heavy mortar fire that frightens the young children in particular and creates for everyone an abiding sense that their secure life is in jeopardy.

The year 1937 marks the irrefutable beginning of the end of a childhood idyll. With the second Japanese invasion of portions of China, everyone experiences a worsening of living conditions, even those in the International Settlement and the nearby French Concession, which had previously been protected by separate treaties. “We knew, but couldn’t absorb, that we would now live surrounded by the Japanese army.”

The vicious assault and murder of a member of the Potters’ household at the hands of Japanese soldiers is the book’s only gruesome moment and signals that a certain way of life is no longer sustainable. In a moment of self-reflection, the author adds, “I learned self-control during this period. When I feel threatened, my feelings shut down. Somehow, I build an inner wall that protects me, or so my system thinks, and enables me to corral my thoughts.”

It takes several years before the noose of international events tightens sufficiently to force the expatriate Potters to leave the country that has been their home for a quarter century. Part of their reluctance to depart is that they have all become unalloyed Sinophiles, absorbing, for example, the Chinese cultural imperative to act in a way that enables others to save face at practically any cost.

By the time the Potters settle in New York in 1941, Patty has enough memories to last a lifetime. And last they do, as this volume attests. Though they are largely memories of happy times, the overarching effect is one of deep sadness, as the writer realizes all too well that the life she so enjoyed as a child was taken away abruptly, and the world in which she was raised has been entirely obliterated by the march of history.

Perhaps the most distinctive element of this excellent book is its organization. While the story of Ms. Chapman’s childhood unfolds in strictly chronological order, each chapter begins and ends with several paragraphs, in italics, in which she engages in a sort of free association that connects elements of her youth to her present-day life. In nearly Proustian manner, for example, the very first chapter begins with an account of her glimpsing, in a hotel lobby in Austin, Tex., a poster picturing the “Grand Hyatt Shanghai (Pudong).”

Suddenly weak, I back slowly, carefully onto the edge of a bench and try to breathe calmly. . . . It cannot be in Shanghai, and certainly not in the filthiest part of the city, Poo Tung. . . .

I knew Poo Tung, Pudong now I guess, when I was a little girl. Shadowy memories slowly snake up out of that amorphous area of the soul where the most private joys and the deepest hurts are preserved.

At the end of the same chapter she writes, “ ‘There’s my home,’ I whisper.”

Thus, the secondary story here — nearly as intriguing as the primary tale of a youthful eyewitness to a slice of history most Americans know precious little about — deals with the rich experience of retrieving memory. Entire worlds are buried within us, the author demonstrates, but they are not necessarily lost.

One interesting stylistic element of this memoir is the author’s willingness to reproduce the pidgin English spoken by her family’s servants and service people, as well as, somewhat curiously, by the family members to the native Chinese workers.

“Little Missee wantchee one piece dumpling?” the vendor suddenly asked. . . .

I held up my empty hands, fingers spread open. “My no got cash, my no can have.”

Those who place a high premium on political correctness may find this troublesome. In the service of accurately reproducing memories, however, I believe it works well — particularly when one acknowledges the mutual respect and affection that the Potters enjoyed with their household employees.

Reading between the lines, it is fairly obvious that Ms. Chapman has written this book, first and foremost, for her children and grandchildren, so that they may lay claim to a distinctive family heritage. In so doing, she has given her progeny a generous gift. Thanks to the book’s publication, we can also sign on as the beneficiaries of her largesse.

A weekend resident of East Hampton, James I. Lader periodically contributes book reviews to The Star.

Patricia Luce Chapman spends summers in Southampton.