An Enigma Wrapped in Letters

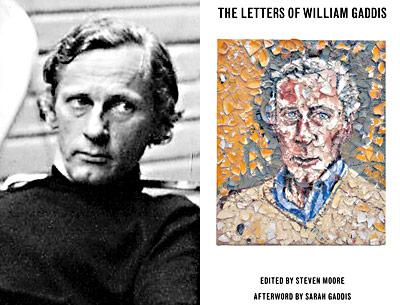

“The Letters of

William Gaddis”

Edited by Steven Moore

Dalkey Archive, $34.50

Among postwar American novelists, no one was more elusive, and thus engendered more curiosity, than William Gaddis (save Thomas Pynchon, of course). In an era when authors like Truman Capote, Norman Mailer, and Gore Vidal used media to their great advantage, Gaddis sat for few interviews, fewer pictures, and, by my counting, only one television appearance.

Even more frustrating to Gaddis fans is the sketchy biography: kicked out of Harvard senior year, a brief stint at The New Yorker, the extensive travels through Europe and South America, followed by the domestic Gaddis — family man and copy and speechwriter for various corporations. Then, at last, awards and modest fame. This is an abbreviation, but barely so — details are desperately lacking.

There are the novels, of course: “The Recognitions,” “J R,” “Carpenter’s Gothic,” “A Frolic of His Own,” and “Agape Agape” — those brilliant, prolix, maddening novels, the second and fourth of which earned him National Book Awards for fiction.

But that’s the art. Where’s the life?

Clearly this obfuscation was exactly what Gaddis intended, having stated his ethos way back with his first novel, “The Recognitions.” “What is it they want from a man that they didn’t get from his work?” asks his painter protagonist. “What’s left of the man when the work’s done but a shambles of apology.”

Well, Bill, since you asked, I would say that there is a natural inclination for readers to be curious about the artists who thrill them. Writing fiction — indeed art in general — is a mystery to those who enjoy it, and often to those who make it. The seemingly mystical connection between an artist and his or her art has been an endless source of fascination and study, and the relation between the two does not seem, to me at least, a superficial or meaningless pursuit. We want to know where it came from!

So there was, for some of us, a sense of excitement when we learned that the Dalkey Press had put together “The Letters of William Gaddis,” culled from nearly 70 years of the writer’s correspondence. Now, finally, we would know something (anything) of Gaddis’s childhood; would find out the incident for which he got kicked out of Harvard; would finally understand how the anti-corporate writer reconciled a working life in the corporate world; would divine just how autobiographical some of the writer’s characters were (such as Jack Gibbs and Oscar Crease, whom we long ago took for Gaddis stand-ins). At last we would have some meat to fill in the flimsy biographical skeleton of one of the more intriguing literary enigmas of the last century.

Or mostly not. For everything you learn about the author in “The Letters of William Gaddis,” there are three things you don’t. This is no fault of the editor, Steven Moore, who assembled these letters and who has been a champion of Gaddis through thick and thin; his footnotes are lavish, if sometimes desperate to fill in the biographical gaps. But in the end, the Gaddis letters are what they are, and what they are is a correspondence of a highly thoughtful, erudite, and occasionally cranky man who was obsessively reticent on the subject of himself and his life. This is of course entirely respectable, not to mention dignified — and frustrating to future biographers and Gaddis fans alike.

What we get instead are dozens of pages of Gaddis thanking his mother, yet again, for money. “Thanks so much for the check — and now if I can collect from my roommate I can see Sylvia Sidney in Pygmalion this weekend too!” This is interesting only insofar as we see how deep into his 20s Gaddis — perhaps already believing himself a genius — is willing to accept cash from Mom.

There are the dozens of letters of Gaddis asking about foreign rights to “The Recognitions” (most of which prove fruitless), dozens more fending off blurb requests from hopeful authors, and more than a handful denying to critics that he was influenced by James Joyce. These letters are polite, if somewhat arch, and after the first two or three, uninspiring to read. Of course this is a writer’s life and we are to expect this sort of thing, the mass of literary dross — but then there is so little of the other. I can’t readily think of a book of letters that — for the first half, at least — reveals so little of a subject’s inner life.

What there is of it mostly comes when the cranky, full-throttled, unpunctuated Gaddis — the Gaddis of the novels — is unleashed through anger or despair. The prepartum of his behemoth, captalist-takedown novel, “J R,” 20 years in the making, gives us a few such nuggets. “. . . I’m doing the same God damned thing all over again with this book & will be 70 for the same idiotic reward, get your God damned picture in the Times and $5500 royalty on it while just your God damned teeth are threatening $8000. . . .”

Here is Gaddis, relieved that he is at the finish line of “J R” because “I’LL NEVER (except for galleys) HAVE TO READ THE INFERNAL BOOK AGAIN! Boy I can’t wait hey. Also maybe I can learn how to talk like an intelligent adult again.”

Then there are the attacks on critics, most of which are shared privately with friends (“Michiko Kamikaze” is a personal favorite) — until he directly takes on Rochelle Girson of The Saturday Review, who foolishly speculates that Gaddis was a rich kid who actually paid to have his first novel published. “Is there, here again, some personal motive?” the author fires back. “If there is not, I do not understand your fraudulent advertisement of my way of living; while yours becomes more embarrassingly and pitifully apparent.” What you get for messin’ with the Man.

With a few exceptions, it is not until the author’s third act that we see Gaddis in a reflective mood and willing to write openly about himself. More often than not, this is conveyed through the lens of regret. By now, the books, the drinking, the breakups, the frustration and lack of success have wreaked their havoc on Gaddis and his family, and the author is not without his insights into his own failings. There’s this to his then-estranged wife, Judith: “I’ve wondered how much your reading J R after all these years of it dwelling in the back room there suddenly exposing itself and myself, has had to do with dormant problems abruptly stepping forth.”

There are passing but sincere mea culpas about the years of drinking. And then, almost unexpectedly, many tender missives to his children, including a glowing review from Dad of the first novel by his daughter, Sarah, “. . . never a bit of self indulgence, so clean, so certain of itself & underivative of others’ styles so full & entirely itself in its haunting sense of desolation utterly uncluttered by sentimentality especially those very last lines which are so spare & simply stunning.”

Probably “The Letters of William Gaddis” is exactly the book we should have expected. “Certainly I was reclusive for years and for damned good reason,” the author writes his daughter. How can anyone buck such dogged reticence? Certainly there is enough of the author here for fans and scholars to weed through and savor, undernourishing as it can sometimes be.

Perhaps, in the end, Gaddis was right (again). You want the author, go to the books. “J R” would be a good place to start. You’ll laugh, marvel at its construction, grow bored and put it down for a month, and, finally finishing it, will feel you’ve experienced more and been taken farther than any interview or “revealing” letter ever could.

William Gaddis lived in Wainscott for many years. He died in 1998.

Kurt Wenzel is the author of the novels “Lit Life,” “Gotham Tragic,” and “Exposure.” He lives in Springs.