Existentialist With a Glock

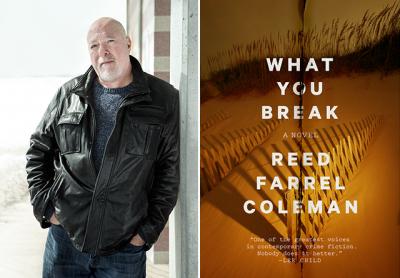

“What You Break”

Reed Farrel Coleman

G.P. Putnam’s Sons, $27

On the copyright page of Reed Farrel Coleman’s new novel, “What You Break,” the book’s genre is identified as “Mystery & Detective / Hard-Boiled.” But Gus Murphy, the book’s narrator and central character, is really closer to poached than hard-boiled. He has the right tough-guy pedigree (ex-cop, bouncer), but any resemblance to the steely shamuses created by Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, and Robert B. Parker is only superficial.

True, Gus’s life is filled with violence, past and present. He tells us that his mentor Bill, an ex-priest, saved his life by killing a rogue cop “who needed killing” after Gus exposed him while on the job. Gus’s Russian friend Slava performed similar services on his behalf “at least twice,” and, he notes, “someone did try to shotgun me in my sleep last year. . . . But so many people had tried to kill me last December that I would have needed a scorecard to keep up.” Understandably, Gus never leaves home without a Glock strapped to his ankle.

Underneath his hard shell, though, he’s both obsessed and depressed. The defining event of his life is the death of his son some years earlier, which cost him his marriage, his job, his belief in God, and his mental equilibrium. “I knew all there was to know about emptiness,” he tells us. “John’s death had supplied me with all the hurt and anger a man could ever need.”

A lapsed Catholic, his catalog of disappointments is suffused with religion: “We were alone and here but once. There was no Heavenly Father waiting in judgment, to guide us, to watch over us, to pull this lever or that.” One of his many antagonists is “nipple deep in hell. I knew because I’d been there myself”; the same man is literally, he believes, the Devil.

At the same time, his angst sometimes takes on an existentialist quality: “What does anything matter after you’re in a box in the ground, when who you are is only who you were and where you’re going is where you are. Forever.” Sam Spade, meet Jean-Paul Sartre.

In addition to blaming the God in which he no longer believes, Gus takes his anger out on everyone he meets: “You’re sorry. I’m sorry. Everybody I know is sorry and he’s still dead,” he says to a woman he’s known for five minutes. He may not have intended this as a pickup line, but it starts her middle-aged juices flowing. “If I was about twenty years younger, there’s no way you’d be leaving here without bedding me,” she tells him, planting a kiss on his 50-year-old lips.

He ignores the hint, but there are two steamy scenes later on, one with his ex-wife and the other with his actress-girlfriend, who, he tells us, enjoys oral sex and “everything bagels with cream cheese.” He’s a much better lover than he is a fighter; three different guys beat him up during the course of the action, and he misses everybody he shoots at.

He isn’t the only one with a cross to bear or a secret to keep. Bill is “a prisoner of his past,” and Slava, because of his connection to a terrorist event decades before, is on the run from a K.G.B. assassin who himself has four identities: He turns up as Michael Smith, Mr. Gordon, Borovski, and Lagunov, which doesn’t make it easy for the reader to follow the convolutions of the story. The biggest secret of all is the horrific past of Micah Spear, a wealthy man of mystery who hires Gus to find out why his granddaughter was stabbed to death.

But even the most minor characters exhibit a reflexive need for privacy: Felix, who owns the motel where Gus lives, “had his secrets,” and Martina, the night clerk, “didn’t seem anxious for me or anyone else to get to know her.”

The plot is Byzantine in its complexity, but the fixed point around which everything revolves is Gus’s need for answers. Some of his questions are factual: Why was the girl murdered, what exactly did Slava do in Chechnya 20 years ago, and what did Spear do in Cambodia two decades before that? Members of a gang called the Asesinos keep turning up (one is the granddaughter’s murderer, who is himself murdered in jail, and two more make an attempt on Gus’s life that is foiled by Lagunov), and everyone is somehow connected to the shadowy Gyron factory that secretly manufactures highly illegal products.

But answering such questions as these is made more difficult by the spiritual colloquy running nonstop inside Gus’s head: “Who could I see about my son’s death? Where were my answers?”

The setting for this tale of multiple mysteries is a prosaic but familiar one: Suffolk County. Gus’s day job is driving a courtesy van for a seedy motel near MacArthur Airport, and the book is in some ways a travelogue of his turf: “Ronkonkoma, Middle Island, and Mastic Beach. Not awful places, just not anybody’s dream.”

Mr. Coleman knows this area intimately and describes it effectively, but the farther east he goes, the less he gets right. Or is it just Gus who thinks that everyone in the Hamptons spends time at “polo matches or regattas”? Gus disapproves of “some huge, inappropriate houses” on Shelter Island, but at least “there weren’t stockade fences everywhere.” So though he is meant to embody the blue-collar cop-and-fireman ethos of central Suffolk, he’s also endowed with taste and discernment: Taking a sip of red wine, he pronounces it “rich with notes of berries and black pepper.”

This is probably meant to introduce some variety into his character, and it points up his resemblance to Robert B. Parker’s Spenser, who knows food and wine and 16th-century English literature, and who, like Gus, is involved with a Jewish shrink — in Gus’s case professionally, in Spenser’s, romantically.

Mr. Coleman is, in fact, continuing the work begun by the late Mr. Parker, writing a series of books with almost indecipherable titles like “Robert B. Parker’s The Hangman’s Sonnet (A Jesse Stone Novel) by Reed Farrel Coleman.” Writing as Mr. Parker, Mr. Coleman’s prose is leaner, more ironic, and more convincingly hard-boiled than it is here. Occasionally, he demonstrates this Parkeresque style in “What You Break”; I wish Gus complained more in the ironic, understated vein of “I hated the way people could become important to me without asking my permission” and less in his usual self-dramatizing mode.

The title, too, is admirably terse. It’s glossed in an unattributed epigraph, which reads, “What you break, you own . . . forever.” That has a nice ring, but what it refers to, in this novel about a man who is not a breaker of things but is himself broken, I have no idea.

Richard Horwich, who lives in East Hampton, taught literature at Brooklyn College and New York University.

Reed Farrel Coleman will read from “What You Break” at Southampton Books on April 8 at 6 p.m.