A Family Affair

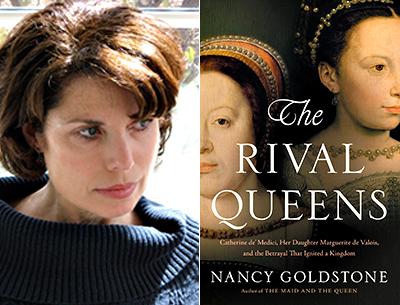

“The Rival Queens”

Nancy Goldstone

Little, Brown, $30

If women ruled the world, begins a contemporary theory, war would become a relic of the past — chiefly because women would never put anything as petty as dominance at the top of their governing agenda. If so, what should we make of Renaissance queens such as Elizabeth I of England, her sister “Bloody” Mary, and the wayward Mary Queen of Scots — or more pointedly, gazing across the channel to France, Catherine de’ Medici, who would appear to have kept a well-thumbed copy of Machiavelli’s “The Prince” on her bedside table?

Whatever reputation for enlightened leadership Catherine may have acquired in the last 500 years, Nancy Goldstone has handily snatched it back in “The Rival Queens: Catherine de’ Medici, Her Daughter Marguerite de Valois, and the Betrayal That Ignited a Kingdom.” Catherine was, in fact, a short, fat, grasping, power-mad hausfrau, frustrated by her husband’s egregious infidelities. “She almost never planned ahead,” writes Ms. Goldstone, in her epilogue, “but reacted moment by moment to varying stimuli.” Catherine lied, cheated, and schemed her way into fiscal and moral bankruptcy. No mere victim of the ruthless time in which she lived, Catherine was the perpetrator of the wars that rocked her country.

Ms. Goldstone has demonstrated her fascination with powerful historic women in books such as “The Maid and the Queen: The Secret History of Joan of Arc,” “Four Queens: The Provencal Sisters Who Ruled Europe,” and “The Lady Queen: The Notorious Reign of Joanna I, Queen of Naples, Jerusalem, and Sicily.” Unwieldy subtitles aside, the author has an impressive talent for turning complicated history into a gripping story — no modest feat in the Valois reign, plagued as it was by the constant struggles between Protestants and Catholics.

The idea of religious tolerance that we have today, notes Ms. Goldstone, didn’t exist during the Renaissance. Trying to understand the tensions, which routinely claimed thousands of lives in battle, can feel like being presented with a complicated algebraic equation with no solution. Who was Protestant and who Catholic shifted, in some cases, as quickly as a tropical storm. Catherine was no great believer herself, though nominally a Catholic; her sympathies usually lay where money, troops, and land could best help her realize the astrologer Nostradamus’s prediction for her sons that “the queen mother will see them all kings.” And, indeed, her sons Francis II, Charles IX, and Henri III would rule France from Francis’s ascension in 1559 (and brief one-year reign) to Henri’s assassination in 1589.

As its title suggests, however, “The Rival Queens” is not about the men. Catherine’s challenger, at least for Ms. Goldstone’s purposes, was her daughter Marguerite de Valois, or Margot — the youngest of her seven children and the only looker. “No, never do I wish to see such beauty again,” said a transfixed Polish envoy who claimed he would willingly burn his eyes out, like the pilgrims to Mecca, at a sight so fine — though history does not record whether he was taken up on the challenge.

Notably, Margot was also a trendsetter, an “It Girl” of the Renaissance. “Is it not you yourself who invent and produce these fashions of dress?” observed Catherine. “Wherever you go the Court will take them from you, not you from the Court.”

As was true for most royal daughters, Marguerite was her family’s pawn — useful to her mother’s ambition to rule France, even as opposing family forces claimed greater legitimacy. When Marguerite’s name was romantically linked with her rabidly Catholic cousin Henri, the Duke of Guise, her mother and brother beat her out of the attachment. “It took nearly an hour . . . for the queen mother to calm her daughter down and fix her appearance,” reports Ms. Goldstone, “as Margot’s clothes had been shredded where they pummeled and scratched at her.”

Catherine’s goal was to marry her daughter to the Protestant Henry, future King of Navarre, heir to the French throne after Margot’s own brothers. In doing so, she hoped to settle the kingdom’s religious and succession issues.

You would be hard pressed to find a more reluctant bride and groom than Princess Marguerite and Henry of Navarre. Nonetheless, “The Rival Queens” turns on their Paris wedding, held on Aug. 18, 1572. Ever ready with a cloak and a dagger, Catherine used the nuptials to put out a contract on Gaspard de Coligny, Admiral of France and leader of the Protestant Huguenots. The first assassination attempt was botched; Coligny’s uncomfortable new shoes, which he leaned over to remove, saved him from taking the hit dead on. Catherine’s efforts to cover her tracks, however, led, on Aug. 24, to a bloodbath of epic proportions. With the slaughter of 5,000 Protestants, “the Seine was choked with bodies,” writes Ms. Goldstone, “the gory remains of disembodied limbs, trunks, and even heads lay strewn in the gutters or piled high in carts.”

The St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, as the event came to be known, turned France’s tensions between Catholics and Protestants into the Wars of Religion. The newly married Marguerite de Valois was damned whether she cast her lot with Henry, the indifferent husband who was deeply suspicious of her, or with her mother, who could not be trusted under any circumstances. Margot saved Henry’s life, repeatedly, only to find herself cast off in favor of his mistresses. Catherine’s notion of motherly love didn’t impede her from conspiring to murder her daughter when their interests collided. The “tragic designs” for Marguerite, reported an ambassador, “would make the hair of your head stand up.”

In this dramatic history, Marguerite de Valois is the Katniss Everdeen figure — the beauteous, seemingly highminded, often hunted innocent. Her flighty reputation, the author believes, stems from Margot’s only surviving correspondence — love letters to Jacques de Harley, seigneur de Champvallon, which make her “look ridiculous.” Margot’s role as an important political figure in France, Ms. Goldstone notes, has consequently been overlooked. While the author puts forward an excellent case for Margot’s level head in matters of diplomacy, the evidence is still also great that her romantic heart frequently ruled her head to her detriment.

You’ll find no dense paragraphs seemingly designed to obscure the truth with scholarly interpretation in “The Rival Queens.” Ms. Goldstone outlines her story in clear prose. She sees her characters as utterly human and their reactions at least explainable, if extreme, under the circumstances.

The conversational asides are refreshing: Margot “was getting the hang” of the espionage game into which she was thrust. A legendary mistress is described as a “patrician bombshell.” However, the platitudes offered up from pop psychology are a little jarring. Do we need to be told that, “even among the most loving and well-adjusted siblings, family dynamics can be tricky”? Or that “there is nothing so hurtful as the realization that a parent loves one child more than another”? In the context of the Valois reign, lines like these come off as jokes.

Ms. Goldstone navigates the history with confidence, occasionally poking fun at its complications. In introducing the young Duke of Guise, another Henri, she adds, “to the despondency of many future historians.” Between Henry of Navarre, later Henry IV; Henri, the Duke of Guise, and Henri III of France, there’s no rest for the reader. But those who keep the story straight will be more than rewarded with enough romance, murder, torture, possible incest, and mayhem to launch a mini-series. Within the Valois family, betrayals are piled upon betrayals, twisted, bludgeoned, and occasionally served with heaping excrement. It’s apt, if sometimes overworked, that the author starts each chapter with a quote from Machiavelli.

The title “The Rival Queens” gives Marguerite more than her due. Margot was no match for the treacherous Catherine — but then who was? Even as kings, Margot’s brothers quaked in their mother’s presence. In the battle between mother and daughter, Catherine won hands down, stripping hedaughter of her husband, family fortune, and the French throne, to which Henry of Navarre ultimately rose as the first Bourbon king, Henry IV.

Still, Ms. Goldstone leaves her readers satisfied. Queen Margot found her happy ending in ceding power gracefully. “I have no ambition and I have no need of it,” she apparently wrote, “being who and what I am.”

Ellen T. White, former managing editor of the New York Public Library, is the author of “Simply Irresistible,” an exploration of the great romantic women of history. She lives in Springs.

Nancy Goldstone lives in Sagaponack.