Fences? ‘Not on Our Beach’

A tussle between the East Hampton Town Trustees and the town’s Natural Resources and Planning Departments over fencing installed on town beaches was a topic of heated discussion at the trustees’ Aug. 27 meeting.

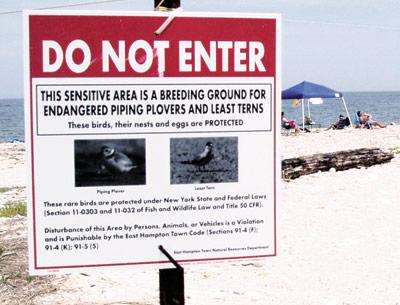

With the conclusion of the nesting season of the piping plover, which the state lists as endangered, and the least tern, which the state considers threatened, the trustees were surprised to see photographs that had been provided by an East Hampton Village police officer. The photos, taken at Georgica Beach, depicted string fencing on metal posts in the sand.

Diane McNally, the trustees’ clerk, sent an e-mail to town employees who monitored the plover nesting areas this year, in which she asked whether the fencing had been erected by the town. According to Ms. McNally, reading to her co-trustees, the e-mailed reply stated, “We are currently conducting a survey for protected beach vegetation on all beaches for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.”

“Not on our beach,” said Joe Bloecker, a trustee, a comment loudly seconded by several of his colleagues.

Mr. Bloecker’s title, and those of his fellow trustees, was created and granted authority over the town by King James II through the Dongan Patent of 1686. As such, the trustees manage the town’s common lands, including beaches.

Ms. McNally read aloud her subsequent response, which stated that the trustees “will have many questions regarding the Town of East Hampton employees conducting a survey for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife [Service] on trustee beaches without having first communicated with us. It’s absolutely mind-boggling that you and your colleagues have not yet grasped the fact that the trustees want to know and approve of any initiatives on the beaches.”

The e-mail went on to ask why the town was utilizing its limited resources to assist the federal agency, insist that the fencing be removed from all beaches immediately, and instruct the town to refer the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to the trustee board for a discussion of vegetation.

The flora in question are seabeach amaranth and seabeach knotweed, said Juliana Duryea of the town’s Natural Resources Department. The state and federal governments list the former as endangered. “We were approached by U.S. Fish and Wildlife to conduct these surveys,” Ms. Duryea said. The species, she said, are generally found within areas the town protects for the plover and tern, “so it makes sense that while we’re taking down fences, we’re surveying for plant species.”

That the town did not consult the trustees or refer the federal agency to it is a problem, the trustees said. The larger problem, said Stephanie Forsberg, a trustee, is the threat of extreme weather such as the hurricanes that struck Long Island in 2011 and 2012. It isn’t about string fencing per se, “it’s string strung along many, many, many metal posts,” she said. “If we wait much longer, we’re going to be in a hurricane and these things are going to end up as trash. I think we’re at the point that, even if we have to foot the bill, we’re going to need to hire someone to take them out,” she said.

Mr. Bloecker suggested that the trustees notify the town’s code enforcement officers. “They don’t have a trustee permit to put that stuff on the beach, period,” he said. “And when U.S. Fish and Wildlife puts their fence down there next year, have them written a violation. If they say it’s their beach, prove it. Otherwise, pay the violation.”

“Let’s at least ask for a violation,” said Ms. Forsberg, reminding her colleagues that extreme weather could arise with little warning. “We’ve been asking for these to come out,” she said. “And being ignored,” said Sean McCaffrey, a trustee, completing the sentence.

“And next year, all fencing must be permitted by the trustees, piping plover or otherwise,” said Mr. Bloecker. “A permit from us,” he repeated.

Steven Papa of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Long Island field office in Shirley wrote in an e-mail that his agency works with other federal, state, and local agencies to conduct an annual census of seabeach amaranth on the south shore of Long Island beaches. East Hampton’s Natural Resources Department, he wrote, “participates in this survey for lands that they manage. In some cases, seabeach amaranth plants are protected with ‘symbolic fencing’ by land managers to protect plants from destruction due to off-road vehicles, beach nourishment, recreational activities, etc.” Mr. Papa defined symbolic fencing as string fastened to posts and said it is widely used by land managers on Long Island to delineate plover breeding and seabeach amaranth growing areas.

Ms. McNally said that management of the birds’ nesting areas, developed jointly by the Natural Resources Department and the trustees, was until recent years a successful effort. She complained that other governing bodies, such as the State Department of Environmental Conservation, have sought to prohibit vehicular access to beaches during the plovers’ nesting season, to which the trustees are adamantly opposed.

State and federal agencies, she said, rely on local authorities and resources to implement their programs. “And then [they] get angry when you don’t do enough?” she asked. “The reason we’re doing this is to keep our beaches open as much as we can. That concept seems to have gotten skewed in the last couple years, and we need to get it back.”

Adding insult to injury, “Out of the blue, this popped up,” she said. “I’ve never heard of us leaving fences up for vegetation.”

Marguerite Wolffsohn, director of the town’s Planning Department, would not comment on communications between town employees and the trustees, but did explain that the program to protect plovers and terns was transferred from the Natural Resources Department to the Planning Department a few years ago. With Kim Shaw now serving as the town’s director of natural resources and Ms. Duryea working in Ms. Shaw’s department, the program is in the process of transferring back to that department. The two departments shared the program’s management in 2013, Ms. Wolffsohn said.