A Festive Memorial To a Life’s Work

Dilapidated buildings on urban streets, flora overtaking abandoned gas pumps on a country lane, the evanescence of a hazy Venice sunset. At Ashawagh Hall, the eyes moved from theme to theme and from subject to subject, witness to how another set of eyes saw the world and committed it to paper and canvas.

Last weekend’s exhibition and celebration of the life of Francesco Bologna could have been a somber affair. Instead, the vitality of the paintings and other artworks and the energy of his family made the show feel as festive as it was intended to be.

Mr. Bologna was 89 when he died in August. Judging by the number of works on the walls, in itself a small sampling, he had a prolific career. He was also well traveled, both internationally and on the South Fork. The subjects ranged from early academic drawings to paintings in New York, then Lucca and Venice, and, finally, East Hampton.

The artist was a realist, in the tradition of true realism, as practiced by predecessors such as Caravaggio, Manet, and Bellows. They painted what they saw, choosing subjects not from the drawing room or the cardinal’s quarters, but the life out there in the streets: the dirty feet, the toothless grins, the prostitute’s room, and the boxing ring. But unlike his predecessors, Bologna wasn’t trying to tweak elite and bourgeois sensibilities. Instead, he saw the “beauty in the mundane.”

In a landscape of stunning vistas, his brushes elevated the simple and the overlooked. There were examples of how development ruined the landscape and how the landscape reclaimed itself, despite the best efforts of humans. Robert Long, writing in The Star, called it an intensity of seeing what was in front of him. He treated the ruins not abjectly, but more like totems or icons.

In Venice, one of his subjects was an American crane on a barge in the Grand Canal, with the usual sites playing a background role. In East Hampton, too, he portrayed a similar piece of heavy equipment, set adrift in a field, next to a rusting oil drum. If Tiepolo and Rubens (the artist’s tribute to Rubens was in the show) were his favorite painters, he must have reserved them for pure enjoyment rather than much of an aesthetic model.

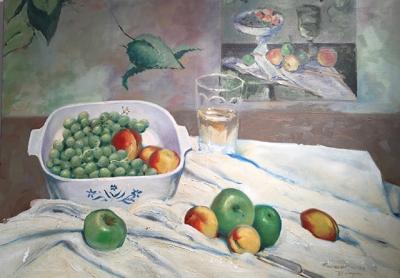

Another compelling tribute is an early still life inspired by Cézanne. The patchily painted greenish-gray interior has a Cézanne-esque painting on the wall with a compote full of peaches and grapes, more fruit on a folded tablecloth, and a wine glass, all set on a proto-Cubist table. They are depicted at such an angle that they would clearly roll off if found in real life. Mr. Bologna replicates the painting, using objects from his own household, putting white wine in a Libbey pint glass, the fruit in a square Corningware casserole dish, using a facsimile of the wallpaper in the painting as his background. His tablecloth is painted in places with a thick impasto. Rather than the relatively neat folds of its inspiration, his takes on a more rippled effect, as if the fruit left out of the bowl had capsized into the whitecaps of a roiling sea. His apples and grapes look worthy of Zeuxis, an ancient Greek said to have painted a bunch of grapes so realistic that birds flew toward it to take a nibble, and would surely fool any bird who might fly in today to see the display.

In the foyer of Ashawagh Hall, his family placed some of Bologna’s more public subjects, two views of the Springs General Store and the front window of The Star’s offices. After observing that painting for several years, it was invigorating to see it in this context. The reflections of Guild Hall and the trees in front of the window might have easily been edited out by a different painter, a Renoir perhaps, who would have seen them as flaws. A painter like Manet or Bologna, however, who witnessed and understood what a mirror on Main Street that window is would want to replicate it just as he saw it. I’ll never look at that painting the same way again.