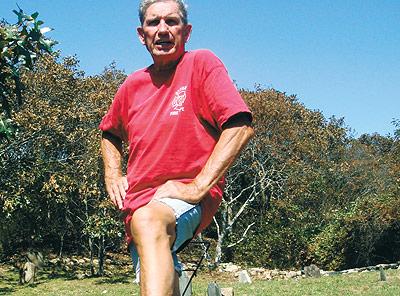

First House Cemetery’s Sole Savior

Each summer, Les Warner of Betham, Conn., and Jacob Hand of Montauk commune over a broad reach of time, two centuries in fact. It’s a silent reunion given the loud rattle of Mr. Warner’s power mower, plus the fact that Mr. Hand has been buried since September of 1813 in a small cemetery in Montauk that Mr. Warner has tended since 1982.

Mr. Warner has been with the Bethany, Conn., Fire Department for 58 years. Each summer, he and his family camp at Hither Hills State Park. He is the self-appointed caretaker of the First House Cemetery and has made it his business to rebuild the low stone wall that borders the boneyard.

He cuts back encroaching vines and brambles, and mows the grass around the dozen or so headstones. Most have been broken into anonymity. Two of the identifiable stones mark the graves of Jacob Hand, first Montauk Lighthouse keeper, and his daugher, Betsy.

The cemetery was originally located near First House, literally the first house cattle herders came to while driving their stock “onto” Montauk from East Hampton each summer. The house was first built in 1744 on land that is now a state park. It burned down and was replaced in 1798. It burned a second time and was never rebuilt.

“When I first came, I wanted to do some exploring,” Mr. Warner said. “The people at the campground said there were dunes and trails. They asked if I’d like to see an old cemetery. In 1981, I discovered it all overgrown with weeds and grass two feet high. The following year, I brought my weed whacker. It was the first time I really saw the stones. It was a pretty spot, but the stone walls were down.”

Mr. Warner said he started rebuilding the walls 8 to 10 feet at a time. “It was all downhill from there. After the first dozen years, the Parks Department started mowing too.”

He has since begun to push back the brush from outside the stone walls to give the cemetery a little — “breathing room” is not right — space.

Jacob Hand was born in 1733. He married Abigail Conklin and the couple raised four children, Ester, Jerusha, Jared (who took over as lighthouse keeper when his father stepped down) and Betsy. He was already 63 when he began his service. He had come highly recommended.

“I know of no one that would give better satisfaction than Mr. Hand, a resident on the land and who I understand has applied. He will be entirely satisfatory to the proprietors of the land,” Henry Packer Dering, collector of customs in Sag Harbor wrote to Tench Coxe, commissioner of revenue, in April 1796.

Mr. Hand ran the Lighthouse frugally for 16 years. “The keeper is a very faithful and careful man and often grows fearful and anxious towards the close of the year that the oil may be expended before a supply may arrive,” Henry Dering wrote.

He first lighted the lamps in April of 1797, five months after the completion of the Lighthouse, whose construction was authorized by President George Washington in 1792.

The light itself consisted of two tiers of four lamps arranged like a chandelier. Five gallons of whale oil were consumed every night. The record shows that Mr. Hand was badly cut by flying glass when a storm he described as a tornado broke more than half the glass out of the lantern.

His job included climbing the 137 steps in the Lighthouse’s circular staircase with a 40-pound jug of whale oil each day. He filled the eight lamps, trimmed the wicks to keep the light steady and bright. His salary was $266.66 per year.

He left his post in 1812 at the start of the second war between England and her former colony. The British never occupied the Lighthouse, but must have felt it would have been a benefit if they could.

According to the fading numbers on his headstone, Jacob Hand died on Sept. 21, 1813, less than a year after his son Jared was appointed keeper.

Mr. Warren said he didn’t actually commune with Mr. Hand as he tended the plot, but “if Jake jumped out of his grave and handed me a cold P.B.R., I would.” That’s Pabst Blue Ribbon beer, he explained.