Gadfly of the Art World

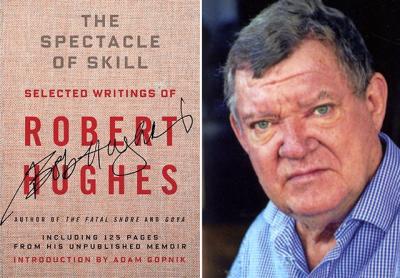

“The Spectacle of Skill”

Robert Hughes

Knopf, $40

The chicanery that prevailed in the unregulated art market of the late 20th century provoked no harsher critic than Robert Hughes. This outspoken art critic left his native Australia for Italy in 1964, landed in London in 1965, and settled in New York in 1970, the year of the painter Mark Rothko’s suicide.

In writing about the efforts of the Marlborough Gallery to “waste the assets” of Rothko’s estate through a conspiracy with the painter’s trustees, Mr. Hughes exclaimed, “the ethical level of the art world is no higher than that of the fashion industry. The problem is not that some dealers are crooks or that most are unabashed opportunists; the same could be said of lawyers. It is that the whole system of the sale, distribution, and promotion of works of art is a terrain vague.”

“Art dealing aspires to the status of a profession, without professional responsibilities,” he lamented. “The flight of speculative capital to the art market has done more to alter and distort the way we experience painting and sculpture in the last twenty years than any style, movement, or polemic.”

When Mr. Hughes, who died in 2012 at the age of 74, wrote in the late 1970s about the changing ground rules of museum-going, he predicted what was to come: “What was once a tomb becomes a bank vault, as every kind of art object is converted into actual or potential bullion.” He wrote about market manipulation, explaining how the Marlborough Gallery could buy a Rothko for $18,000 and two years later offer it to Mr. Hughes’s own acquaintance for $350,000. But Mr. Hughes died not long after the Knoedler Gallery closed, accused of selling for millions fake Rothko canvases that turned out to have been painted by a Chinese artist living in Queens.

To review “The Spectacle of Skill: Selected Writings of Robert Hughes” is, for me, an exercise in nostalgia. For more than three decades, Mr. Hughes loomed large as the influential art critic of Time magazine, which Adam Gopnik, in his introduction to this volume, dismisses as “a bible of middlebrows, an ornament of the dentist’s office.” But that was the point. We, who labored as museum curators, hoped to win his approval since Mr. Hughes energized and enlarged the audiences for our shows and created readers for our catalogs.

I am lucky to have worked on projects and artists that Mr. Hughes liked — from exhibitions of Edward Hopper to the formative years of Abstract Expressionism. When researching my biography of Lee Krasner, whom Mr. Hughes had dubbed “the Mother Courage of Abstract Expressionism,” I spoke with him and found him lucid and approachable. Yet Mr. Hughes was notoriously opinionated and not afraid to appear or to be politically incorrect.

This recent book includes writing from Mr. Hughes’s unfinished second volume of memoirs as well as a selection of pieces from most of his 14 previously published books, starting with “The Shock of the New,” from 1980, and omitting his first two books, “The Art of Australia” (1966) and “Heaven and Hell in Western Art” (1969). There are excerpts from his two books on great cities, “Barcelona” and “Rome,” and from his biography of Goya, whom he labels one of the “seminal artists,” and even an essay on fishing.

There are accounts of his adventures in television, including a very brief stint as a co-anchor of ABC’s news program “20/20.” Mr. Hughes turned out not to be a good fit, but he tells how he earned more for doing one program than he did for years of writing about art. For a series of eight televised programs called “The Shock of the New,” which he made for the BBC, Mr. Hughes explained that the title was borrowed, at the BBC’s insistence, from Ian Dunlop’s earlier book on seven modernist exhibitions. Mr. Hughes admitted to having had many collaborators, but told how he “fleshed out” each of the scripts for the book version. He wrote with a kind of clarity and eloquence that made his writing memorable.

In his essay on Edward Hopper from his 1997 book, “American Visions,” I find many of my own original interpretations, though without any acknowledgment. Just as in his other essays, Mr. Hughes repeats and distills the ideas of many other unacknowledged authors. I know that he read my early writings on Hopper, for he reviewed favorably my exhibition and its book-length catalog, “Edward Hopper: The Art and the Artist,” and even reprinted that review in his book of collected essays “Nothing if Not Critical” of 1990, writing, “The Whitney Museum of American Art’s retrospective of Edward Hopper, curated by Gail Levin, may be the only incontestably great museum exhibition of work by an American artist in the last ten years.”

I was thrilled at the time to have his approbation. I am happy to see that he has since recognized the essential role of Jo Nivison, Hopper’s wife and only model, though he brands her a “ ‘difficult’ woman, trapped between the role of supportive wife and her own creative ambitions.” Our respective observations on Hopper’s wife are all filtered through the lens of our gendered identities. In general, however, I find that Mr. Hughes was less an original thinker than he was adept at synthesizing the ideas of others, injecting his own strong opinions, and reflecting the cultural climate of his time.

Despite his own ability to borrow ideas from others and then shape these unacknowledged borrowings into powerful prose, Mr. Hughes was critical of similar practices by visual artists. He attacked the work of artists such as Julian Schnabel and Jean-Michel Basquiat. The latter essay, unfortunately subtitled “Requiem for a Featherweight,” has not been included in this volume of selected writings, though the Schnabel piece does appear. But elsewhere, from his unfinished memoir, we find: “ ‘The Eighties’ turned out to be very different indeed, a figurative ‘revival’ conducted by the worst generation of draftsmen in American history — Julian Schnabel, David Salle, Jean Michel-Basquiat: the all-too-familiar chorus line of spectacular mediocrity and even more spectacular price inflation.”

Mr. Hughes’s skepticism toward what he called “recycled expressionism” was fierce: At the time, he accused Mr. Schnabel of using “Gaudi-derived plates and Beuys-derived antlers,” calling him “a most eclectic artist; what you see in his paintings is what he was looking at last.” He attributed Mr. Schnabel’s success to his ability to meet “the nostalgia for big macho art in the early eighties . . . only a culture as sodden with hype as America’s in the early eighties could possibly have underwritten his success.” Mr. Hughes did not anticipate Mr. Schnabel’s later success as a filmmaker, starting with “Basquiat” (1996), a poignant film about his friend and fellow art star’s short and tragic life in art.

In his own published memoir, “Things I Didn’t Know,” which focuses on his childhood and youth in Sydney, Australia, as well as his formative time in Italy, Mr. Hughes was less judgmental.

But then his unfinished memoir reveals Mr. Hughes behind the scenes during his New York years. He was indiscreet, telling about his affair with the art critic Barbara Rose, shortly after she was divorced from the artist Frank Stella. “Her affairs with other artists and writers were numerous and labyrinthine,” he writes, “she was, to put it mildly, attracted to talent (and vice versa), and she had a way of convincing herself that whatever talent her inamorati possessed was created, or at the very least improved, by her.” He credited “a good deal of what I discovered about New York art in the early seventies” to her.

Mr. Hughes goes on to describe the artist Helen Frankenthaler, whose art he states was in Ms. Rose’s vast collection of artists whose work she had reviewed, as “The complete princesse juivre. What a pair she and Barbara Rose made, with their ironclad egos, their elaborate systems of dependency, their high style / low style fluctuations. . . .”

For their corruption — essentially for taking payments of art to write seemingly objective pieces published as “reviews,” or being paid off for choosing contemporary artists to be in museum shows — Mr. Hughes railed against many critics and curators, from Bernard Berenson to the critic Clement Greenberg, who he wrote rationalized “his practice of living on freebies.”

Mr. Hughes singled out with particular vehemence Henry Geldzahler, the first curator of contemporary art at the Metropolitan Museum, as “the short, cherubic son of a Manhattan diamond dealer . . . [whose] academic qualifications for the new post were slender at best.”

But then Mr. Hughes himself admitted to selling a large unprimed Frank Stella canvas — that he had bought earlier — to purchase his loft in SoHo, as the building was going co-op. He expressed his chagrin that his Stella, unlike those in photographs in House and Garden of “whole white walls of crisp white interiors in the perfect Upper East Side townhouses of pristine, flawless, and white Jewish collectors,” had gotten soiled.

Mr. Hughes has sometimes been taken to task for being politically incorrect, for not paying adequate attention to women and minorities. But here, in his essay on James McNeill Whistler (previously collected in his 1990 volume), he labels the artist “a virulent racist . . . who did not confine his obloquies to blacks and Jews.”

I last encountered Mr. Hughes at a dinner party of mutual friends, Jewish art dealers. We spoke about Lee Krasner, whom we both knew and admired. What comes through in his last memoir, however, is Mr. Hughes’s particular sense that he was an outsider who happened to land well in the New York art world. This comes through most clearly in his report of the response made by Barbara Rose’s parents when they chanced upon him repairing his motorcycle while dating their daughter: “Who is that shegetz you have in the yard? The schmutzig one with the black jacket?”

Gail Levin is a distinguished professor of art history at the City University of New York and an exhibiting artist.

Robert Hughes lived on Shelter Island for many years.