A Gastronomic Liberation

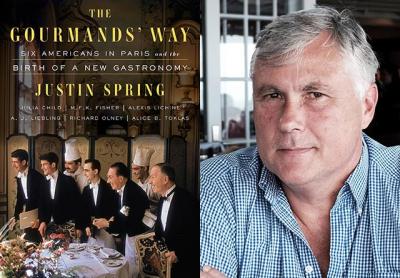

“The Gourmands’ Way”

Justin Spring

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $30

In this era of the Food Network, local sushi and ramen bars, and international ingredients readily available at your neighborhood supermarket, it may be hard to fathom how provincial America’s relation to food once was. Just a century ago there was virtually no European or Asian influence on our nation’s menu. As Justin Spring argues in his new book, “The Gourmands’ Way: Six Americans in Paris and the Birth of a New Gastronomy,” it took two world wars and a handful of Americans abroad to drag European cooking to this country.

In this well-researched, fun, and beautifully written book, Mr. Spring chronicles the lives of gourmands who shared their knowledge of French food and wine with a prosperous postwar America. The six chronicled here are M.F.K. Fisher, A.J. Liebling, Richard Olney, Alexis Lichine, Alice B. Toklas, and Julia Child. Though their expertise was diverse, their timing was impeccable. As Mr. Spring writes, by the 1950s, “Americans were tired of the austerity mandated by the Great Depression and World War II. They wanted a return to abundance and pleasure, and they now had the money and leisure to pursue both.”

While advertised as a “biography” of six individuals, “The Gourmands’ Way” is much more fun than that. Rather than formal profiles, Mr. Spring weaves the lives of his subjects into a larger narrative that is surprisingly lively and engaging.

He begins, as all food writing probably should, with the incomparably voracious A.J. Liebling. As a journalist who covered World War II for The New Yorker from Paris, Liebling exploited a diminished French currency while indulging his Rabelaisian eating habits (much of which is recorded in his masterpiece “Between Meals”). Liebling’s idea of the perfect Normandy lunch, for example — as recounted by Mr. Spring — began with a few dozen oysters, moved on to spider crab, then a slow-baked casserole of cow stomach enriched with calf’s foot, a partridge, a leg of lamb, and a few steaks. More wines are consumed than there is time to enumerate, and everything ends with multiple bottles of Calvados brandy. Presumably there was a cardiologist on standby.

Though some will luxuriate in these loving descriptions of gluttony — of which there are many in Mr. Spring’s book — vegans and animal lovers need beware. The gourmands profiled here were all meat-eaters par excellence. Take, for example, the food writer Richard Olney and his taste for ortolans (or songbirds). The recipe, as reported by a friend of Toklas’s in The New Yorker, calls for the birds to be kept in a dark room to keep them “drowsy and inert,” and they are “stuffed in the gloom for a fortnight with millet seed. . . .” They are then force-fed Armagnac for what Olney called “the sacrifice.”

The ritual of eating them is just as charming. Also from The New Yorker: “The eater is supposed to seize them by the beak with the fingers of one hand and consume them, bones and all, beginning with the feet. . . . Old engravings show ortolan-eaters with napkins hoisted like tents over their heads to enclose the perfume. . . .”

Grotesqueries aside, there are some lovely portraits of a forgotten Paris, particularly in the chapters profiling Toklas, the lifelong companion of Gertrude Stein, who finds herself suddenly widowed and living without a franc to her name in Stein’s momentous Paris apartment. With Gertrude’s estate contested by her avaricious brother, the Picassos and Cezannes on the walls are of no use to Alice, her sitting room, as Mr. Spring writes, “chockablock with modern masterpieces, yet threadbare and as cold as an icebox.” (Later, Toklas would go on to financial solvency with “The Alice B. Toklas Cook Book,” which presciently included a recipe for hashish brownies!)

Then there is the newlywed Julia Child, satisfying her randy husband’s sexual desires in the afternoons (who knew, Julia!), then hurrying over to the Cordon Bleu school for cooking classes. She apparently had “no patience for the dirt, worn crockery, faulty electric ovens, and overall mismanagement she encountered there”; it is a portrait of decrepitude that runs counter to the idea of the Cordon Bleu as the grand cathedral of culinary France.

The successes mount. M.F.K. Fisher, Olney, Toklas, and Liebling all become indispensable American writers. Alexis Lichine, the self-described “Merchant of Pleasure,” brings French wine to the masses, becoming rich in the process. And Julia Child, of course, becomes a fixture on American public television.

In the mid-1960s, however, this Franco invasion begins to run its course, the rift spurred by a burgeoning French economy and tensions between Charles de Gaulle and Lyndon Johnson over America’s involvement in Vietnam. By then, however, the wool was fully dyed, with restaurants like Le Pavillon and La Cote Basque already having become American benchmarks, and the New York Times food critic Craig Claiborne declaring French haute cuisine as “the best in the world.” Even President John Kennedy got into the act, announcing in 1961 that “every man has two countries — France and his own.”

It is this legacy that Justin Spring so strongly evokes in “The Gourmands’ Way,” a loving portrait of food obsession and the people who liberated American cuisine from its provincial doldrums.

Kurt Wenzel is a novelist, regular book reviewer for The Star, and former restaurant critic for The New York Times. He lives in Springs.

Justin Spring’s previous book, “Secret Historian: The Life and Times of Samuel Steward, Professor, Tattoo Artist, and Sexual Renegade,” was a finalist for a National Book Award. He lives in Bridgehampton and New York City.