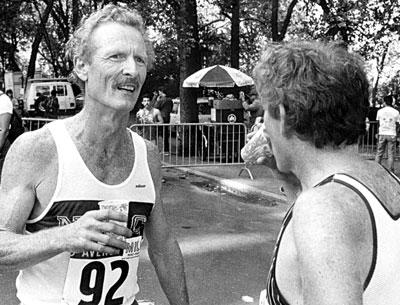

Gotta Beat the Agon, Says John Conner

When this writer recalled that John Conner ran the Fifth Avenue Mile in 4 minutes and 40 seconds at the age of 50, he was corrected by the interviewee: “Four-forty point one.”

That’s by way of saying that runners remember their times, and Conner, who’s bearing down on his 78th birthday come February, and who has professed the desire to live to 200, has many exceedingly good times — including three world records and nine national championships — to remember.

One of the best age-group milers and half-milers in the world in his 50s and 60s, his running career, abetted by credit card air miles that once totaled one million, was cut short about 11 years ago when a truck struck him from behind as he was cycling in East Hampton Village.

Undaunted by a shattered hip, which was put back together with screws and flanges by one of the country’s best orthopedic surgeons, he became a top age-group triathlete, and though he now walks with a cane, he continues to walk, swim, and bike — early in the mornings before the sun comes up.

In 1990, at the age of 55, he set world records for 55-to-59-year-old runners in the 800 (2:10.62) and mile (4:53.3) races — times that most high school runners would envy — and followed up in 1995 with a world record in the 1,500.

For the past five years, Conner, a retired general contractor who built affordable houses here for many East Hampton families, and who, before that, was the director of Head Start, and who, before that, was an artist, winning “best in show” at Guild Hall in 1962, has been coaching a group of serious runners, young and old, at East Hampton High School’s track.

Under his watchful eye, and as the result of his methodical workouts designed to strengthen hearts and lungs and muscles, all have improved their times, whether they’re 16 or 64, whether their race is the marathon or the mile.

“Glenn Cunningham, a great miler of the ’40s, once said,” said Conner, with a meaningful smile, “ ‘Running is you against yourself . . . the cruelest of competitors.’ ”

“In other words, you can take yourself to the limit and then you can go further! Running is a struggle, it’s the Agon — that’s the Greek word for it. All the speed work, all the cardiovascular work, comes down to this: You want to get into as much stress as you can handle and then equalize things so you have enough oxygen to remove the lactic acid — which is what makes you tired — and thus continue running at a high level. If you’re in shape, you can, in the shorter distances, continue at your pace despite oxygen debt.”

“What’s oxygen debt?” He rose from his chair to explain. “It’s what they call the bear grabbing you. It’s when lactic acid takes over. You’re 50 yards away from the finish line and you’re freezing up. All of a sudden, you can hardly lift your knees anymore and your head lolls back and you’re gasping for air. That’s oxygen debt.”

When asked if he’d been a world champion, Conner replied, “No, I was never a world champion — I was a world record holder. There’s a difference. It’s much harder to win a world championship. At a world championship [he’s contended in them in Finland, Australia, Italy, and Canada] you’ve got eight great, great, great fucking runners on the line and all of them have a plan, which to beat you! It’s a horse race.”

The last national championships he’d won had been in 1995 in Reno, Nev. “I won the 800 and the 1,500 there. Cliff Pauling, my nemesis — we battled each other for 15 years — would beat me in the 400, I’d beat him in the mile, and the 800 was always a tossup — wouldn’t line up against me in the 800 that time. . . . To win the 800, you need speed, stamina, you can’t make a mistake, and you need a little luck.”

“To make a runner,” Conner continued, “takes five years, sometimes longer. I tell the kids who come to my workouts that I’m not out to make them faster, I’m out to make them stronger. . . . When the heart is ‘juicier,’ it can pump 20 quarts of blood rather than 12; new capillaries are opening up when you exercise, you’re bringing more ‘gas,’ more glucose and oxygen to the muscles. . . .”

And then, he said, there was the spiritual side (the Paraclete, the Holy Ghost, what you will). “Before Roger Bannister broke the four-minute mile in 1954, everyone was saying it never could be done, that it would take too much energy, create too much lactic acid, and that the body couldn’t do it. Bannister was a wonderful scientist. He knew he could do three laps in three minutes and he told himself not to think about the fourth. In that fourth lap he was beyond the physical, in a different realm. That’s where the theory of oxygen debt and the ability to perform at a high level despite it came from.”

“There’s a saying, ‘The body will remember.’ I remember it from my high school days at Delbarton. My coach was a Benedictine monk. He told me that if I got into good shape I could do more. . . . The body yearns for exercise. It’s amazing what it can do. I’ve tried to get the kids to become their own GPS, to know what it is to run at a six-minute-per-mile pace, to hold their form, and then, when they’re heading toward the line to take on an attitude, to say to themselves as someone’s coming up on their shoulder, ‘Who’s this intruder?!’ And then to run through the line. You gotta win the struggle against yourself, you gotta beat the Agon!”