A Gracious Wit

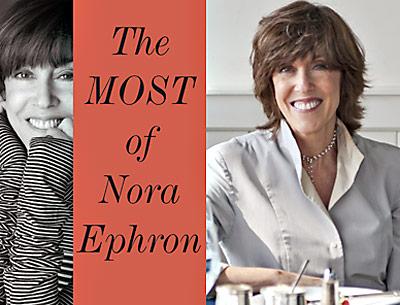

“The Most of

Nora Ephron”

Alfred A. Knopf, $35

When Nora Ephron died last year at the age of 71, there was an outpouring of personal and public grief greater than any I can recall for a contemporary American writer or film director. I knew her only as an acquaintance, an always charming and gracious presence, but her close friends still speak of other, more compelling qualities, especially her extraordinary generosity to those younger women — neophytes in her own professions — whom she mentored and encouraged.

Many elegiac essays about her life and work appeared not long after her death, including those by her son Jacob Bernstein in The New York Times Magazine, her sister and collaborator, Delia Ephron, in her collection “Sister Mother Husband Dog (etc.),” and the actress Meg Ryan in The Hollywood Reporter. And now there is this hefty, posthumous compendium of Nora Ephron’s writing, with a telling and affectionate introduction by Robert Gottlieb.

One of the many pleasures of “The Most of Nora Ephron” is its variety: a novel, a screenplay, a theatrical script, numerous essays, and a scattering of recipes, all gathered between two covers that bear the same appealing photograph of the author. Another bonus for the reader is the common thread that binds these seemingly disparate works — Ephron’s constant, distinctive voice. It reflects what her family, friends, and colleagues have all said about her — that she was original, hilarious, brave, disciplined, sarcastic, confident, modest, and honest.

In “The Art of Fiction” Henry James instructed, “Try to be one of the people on whom nothing is lost!” And when Ephron’s mother was dying, she said, “You’re a reporter, Nora. Take notes.” Nora Ephron seems to have taken both of these directives strongly to heart. A keen observer of everything from Washington politics to sexual politics, she was outspoken about all of it.

She wrote directly and indirectly about her own life, lamenting her small breasts in a famous Esquire essay (with a killer last line) and the traumatic end of her second marriage in the novel “Heartburn.” The fictional Rachel, like the real Nora, is seven months pregnant with her second child when she learns that her husband is in love with someone else. “The most unfair thing about this whole business,” Rachel remarks, “is that I can’t even date.”

Ephron has been criticized for this kind of levity, for putting a cheerful gloss on serious matters. But in a piece called “The D Word,” she says of this second divorce, “I wrote about all this in a novel called ‘Heartburn,’ and it’s a very funny book, but it wasn’t funny at the time. I was insane with grief. My heart was broken. I was terrified about what was going to happen to my children and me. I felt gas-lighted, and idiotic, and completely mortified.”

Later on she writes, “Now I think, Of course. I think, Who can be faithful when they’re young. I think, Stuff happens. . . . My religion is Get Over It.” Of course a lot of time had passed by then and she had (sort of) gotten over it. (And her third marriage, to the screenwriter Nick Pileggi, was deeply happy.)

But her metamorphosis also seems to have been a way of coping, of using what she did best to come to terms with what hurt the most. Of course you could also simply call it denial, as she did herself, about turning 60, in her book “I Feel Bad About My Neck.” “Denial has been a way of life for me for many years. I actually believe in denial. It seemed to me that the only way to deal with a birthday of this sort was to do everything possible to push it from my mind.”

Nora Ephron felt bad about more than just her neck, or about numerous other negative aspects of aging. In brief, succinct pieces, she shares her displeasure with, among myriad offenders, exercise (“I would rather be in Philadelphia (although not in labor)”), e-mail (“Call me”), egg whites (“As for egg salad, here’s our recipe: boil eighteen eggs, peel them, and send six of the egg whites to friends in California who persist in thinking that egg whites matter in any way”), and George W. Bush (“I kept America safe, except for this one time”).

The most disturbing and moving references in “The Most of Nora Ephron” are to the writer’s mother, for whom she felt understandable ambivalence. Both of her parents — the screenwriting team of Phoebe and Henry Ephron — drank heavily, but Phoebe was “a crazy drunk” who “would come flying out of her bedroom, banging and screaming and terrorizing us all,” and died of cirrhosis of the liver at the age of 57.

The Ephron household can be seen, from a considerable distance, as enviably privileged and glamorous: Beverly Hills, the cook and maid and laundress, that plethora of famous Hollywood pals. Up close, though, it must have often been a nightmare.

Phoebe Ephron gets a lot of quote space in her daughter Nora’s account. That deathbed edict to “take notes” is frequently counterpointed by “Everything is copy” — invaluable advice, no doubt, for budding journalists. But she doesn’t come across as particularly maternal in these pages, or in the published recollections of her other daughters. Ephron writes: “For a long time before she died, I wished my mother were dead. And then she died, and it wasn’t one of those things where I thought, Why did I think that? What was wrong with me? What kind of person would wish her mother dead?”

Yet she struggles with her feelings. “Alcoholic parents are so confusing. They’re your parents, so you love them; but they’re drunks, so you hate them. But you love them. But you hate them.” Only a convoluted incident involving Phoebe Ephron and the writer Lillian Ross, related in this same essay, manages to mitigate Nora’s rage and restore her early, innocent filial love. “I got her back; I got back the mother I’d idolized before it had all gone to hell.” This passage reads like that coping mechanism at work again, rather than mere whitewashing or denial.

Less than two years before Nora Ephron’s death — from pneumonia, a complication of acute myeloid leukemia — which had been foretold by her doctors, but kept from everyone but her immediate family and a few friends, she wrote, “Sometimes . . . we go to Los Angeles, where there are hummingbirds, and I love to watch them because they’re so busy getting the most out of life.” Keeping her dire illness a secret doesn’t appear to have been just a matter of preserving her privacy. Ephron clearly knew that the inevitable spate of sympathy following such news would get in the way of her work, of her ongoing plan to get the most out of life.

With mortality in mind she made two lists. The one headed “What I Will Miss” is topped by her kids and her husband, followed by a catalog of pleasures like Shakespeare in the park, reading in bed, and taking a bath. Dry skin, bar mitzvahs, the sound of the vacuum cleaner, and Clarence Thomas all made it on to the second list, “What I Won’t Miss.”

She even organized her own memorial service, down to the timing for each speaker. But she also continued writing after her diagnosis, completing, most notably, the play “Lucky Guy” — about the tabloid reporter and columnist Mike McAlary — although she didn’t live to see its Broadway production, starring Tom Hanks.

One can only wonder, wistfully, what Ephron would have made of some of the newsworthy events that have occurred since she’s been gone. She’d surely have had much of interest to say about the recent government shutdown, the outbreak of gun violence in this country, and the Cheney family falling-out over gay marriage. It’s too bad that we won’t get to read any of it. But at least we have the consolation of this big, enlightening, and thoroughly enjoyable volume.

And all those recipes to try, besides. I’m going to start with the succotash.

Hilma Wolitzer, formerly of Springs, lives in Manhattan. Her most recent novel is “An Available Man.”

Nora Ephron had a house in East Hampton for many years.