The Great Philately Chase

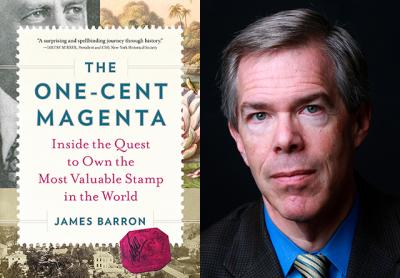

“The One-Cent Magenta”

James Barron

Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, $23.95

Among the most gratifying reading experiences one can enjoy is to penetrate a book that, at first glance, appears to be esoteric or of little interest, only to find it riveting. Daniel James Brown’s “The Boys in the Boat” and virtually anything by John McPhee jump to mind as examples of this phenomenon.

I had hoped that would be the case with James Barron’s recent book, “The One-Cent Magenta: Inside the Quest to Own the Most Valuable Stamp in the World.” After all, Mr. Barron’s previous book, “Piano: The Making of a Steinway Concert Grand,” had been a compelling read. Alas, this time I was disappointed.

The subject here is the history of the rarest, and thus the most valuable, postage stamp ever issued and, by extension, the arcane world of philately, which the author, a well-regarded New York Times reporter, calls Stamp World.

The essence of the book is contained in nine sentences on the back of the jacket:

In 1856, a batch of one-cent magenta stamps were printed, sold, and forgotten.

In 1873, a twelve-year-old boy discovered one of those stamps in his uncle’s basement but had no idea it had become a rarity.

In 1878, the stamp got a spot in the castle of a fabulously wealthy French nobleman.

In 1922, it was bought by an American plutocrat, who may have burned a second one-cent magenta so that this one would remain the only one in the world.

In 1933, the plutocrat’s widow claimed it even though her estranged husband’s will stated the one-cent magenta was not hers to inherit.

In 1940, the stamp was sold by Macy’s to a mysterious buyer who was not identified for three decades.

In 1970, it was acquired at auction by a syndicate led by an entrepreneur who traveled with the stamp in a briefcase handcuffed to his wrist.

In 1980, it was purchased by John E. du Pont, who would later die in prison while serving a thirty-year sentence for murder.

In 2014, it was won at Sotheby’s by a celebrated shoe designer for almost $9.5 million.

On the one hand, that’s all you need to know. On the other hand, the remainder of Mr. Barron’s 241 pages of text is fleshed out by his skillful digging into the essential facts listed above.

The one-cent magenta was “an accidental icon. It was not supposed to be so special.” In 1856, the postal authorities in British Guiana (the country now called Guyana) failed to receive a shipment of 100,000 postage stamps from London. The colonial postmaster commissioned a local newspaper to print a batch of “provisional” stamps in two denominations — two-cent stamps for letters and one-cent stamps for periodicals. It is not known how many were produced, nor how briefly they were in circulation.

The stamps lacked artful design and were not aesthetically pleasing. Over time, that has ceased to matter. As any collector (or student of economics) well understands, what matters is rarity. And in this case, there seems to be but one. Unique in all the world, as they say. That’s the only thing a committed collector needs to know.

As one might expect, the one-cent magenta’s value has increased exponentially over time. Recounting its odyssey chronologically, Mr. Barron emphasizes this point by titling each chapter, beginning with the third, with the stamp’s value at the time. What sold for one (British) cent when it was issued in 1856 sold for six shillings in 1873, £120 five years after that, $32,500 in 1922, and so on. Chapter 11, about the American shoe designer Stuart Weitzman’s 2014 purchase of the one-cent magenta, is titled “$9.5 million.”

Some of Mr. Barron’s background digressions are particularly worthwhile. He notes, for example, the history of the British postal service. Until the 1830s, one could “post” (or mail) things for free. It was incumbent on the recipient to pay. The problem was, they often didn’t, and the postal service was losing a great deal of money. The biggest culprits were newspapers, which were all sent and delivered by post at the time. (There’s a slap-on-the-forehead moment when one realizes why so many newspapers have the word “Post” in their names — not to mention The Saturday Evening Post, the American magazine of revered memory.)

In 1839, Rowland Hill, an English educator, proposed a system of postal reform, the centerpiece of which was that senders would pay postal fees, and a stamp would be affixed to each item sent to prove that the mailing costs had been paid in full. The postage stamp was born — at heart, a tax stamp.

Within a short time, the collecting of stamps (with their implications of exotic places and great distances crossed) became a popular obsession worldwide. Mr. Barron’s discussion of the imperfection of the coined term “philately,” for the interest in stamps, provides a distinct Aha! moment.

In terms of his central focus, however, the one-cent magenta stamp and those who have owned it, this is really a small book. (Measuring 5 by 7 inches in size, that is literally true, as well.) It might have been more successful as a featured article in The New York Times Magazine.

The difficulty is that there is not much by way of the elements that contribute to a gripping story. There is no real dramatic tension, no sustained mystery, no captivating characters, and no awe (as in the transformation of raw materials into a musical instrument capable of producing sublime sound).

“The One-Cent Magenta” is likely to appeal most to committed philatelists. And they, as Mr. Barron acknowledges, make up a dwindling population.

Mr. Barron writes well and with perfect clarity. His reporting skills are sharp. In the future, one can only hope that these talents will be applied, once again, to a more worthy subject.

A weekend resident of East Hampton, James I. Lader regularly contributes book reviews to The Star.

James Barron will sign books at the East Hampton Library’s Authors Night on Aug. 12 and be the guest at one of its fund-raising dinners. He has a house in East Hampton.