The Great Scorer

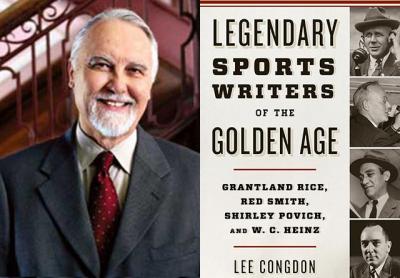

“Legendary Sports

Writers of the

Golden Age”

Lee Congdon

Rowman & Littlefield, $35

He may have written, in verse, about the “One Great Scorer” in the sky who will note for eternity “not that you won or lost — but how you played the Game.” And his first name may have adorned a popular sports website that paradoxically contributed to the dismantling of his beloved world of print journalism. But the most important thing to know about Grantland Rice might well be that he enlisted as a private in World War I when he was 37 years old, a father, and famous. He declined an assignment to Stars and Stripes and requested the front lines, seeing action as an artilleryman in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive in the fall of 1918.

Rice, from Murfreesboro, Tenn., a grandson of a Confederate soldier who fought there, wasn’t debilitated or even disillusioned by the war, but rather saw it as a demarcation. Having grown up before 1914, “that more innocent period in U.S. history remained, for him, the world as it ought to be,” Lee Congdon, a professor emeritus of history at James Madison University, writes in “Legendary Sports Writers of the Golden Age.”

His code of honor was reflected in his writing, notably in his ongoing criticism of the boxer Jack Dempsey, who, for all his ferocity in the ring — at 6-foot-1 and 187 pounds he won the heavyweight title by destroying a 6-foot-6, 245-pound Jess Willard — was essentially a draft dodger.

Dempsey is important here as one of the four towering figures of the sporting “golden age,” as popularly conceived, meaning the Roaring Twenties, along with Babe Ruth, Bobby Jones, the courtly Southerner who almost single-handedly popularized the game of golf in this country, and Red Grange, the “Galloping Ghost” at the University of Illinois, who as a halfback with the Chicago Bears elevated professional football, “once a shabby outcast among sports,” as The New York Times had it in 1938, into “a dignified and honored member of the American athletic family.” (For what it’s worth, Mr. Congdon considers the golden age to extend through the Great Depression and all the way up to the ultimate loss of innocence, the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy.)

College football was Rice’s favorite sport, as was borne out in his most famous opener, in which in 1924 the former Vanderbilt classics major compared the Notre Dame backfield to the Four Horsemen: “Famine, Pestilence, Destruction, and Death . . . the crest of the South Bend cyclone before which another fighting Army football team was swept over the precipice. . . .”

Florid perhaps, overblown, but at least creative and memorable. Rice’s enthusiasm, however, often got the better of him when it came to hyperbole. Back to Dempsey, from a lead paragraph: “In four minutes of the most sensational fighting ever seen in any ring back through all the ages of the ancient game. . . .”

But with the benefits of time and distance and a smaller audience, he could be more rigorous: “Dempsey’s face was a bloody, horribly beaten mask that Tunney had torn up like a ploughed field.” (This was the fight after which Dempsey famously told his wife, “Honey, I forgot to duck.”)

Furthermore, in his memoirs, Rice, who died in 1954, wrote of boxing as indecent, plagued by “thugs, crooks, cheaters, bums, and chiselers.” He could also, at the end of his life, anyway, be prescient, becoming “alarmed by the win-at-any-cost approach of many football coaches and players,” Mr. Congdon writes. As Rice himself put it, “If football isn’t character-building it is no game to be played.”

In a 1951 issue of Sport magazine, he lit into college presidents in an open letter that lamented the quasi-professionalism of college football — long before the advent of the lucrative television contract, decades in anticipation of more sophisticated critics like the late Frank Deford, and roughly 30 years in advance of ESPN’s hyping of players practically into superheroes.

The height of his influence, however, came with his syndicated “Sportlight” column, which began in 1915, when he moved to The New York Tribune, and which “made him the most famous and highest-paid sports writer in the United States,” according to Mr. Congdon, enabling him a dozen years later to build a mansion on West End Road in East Hampton Village.

In those years Rice was solidly in the Gee Whiz school of hero worship, as opposed to the jaundiced Aw Nuts school of cynics and fiction writers like Damon Runyon and Ring Lardner, and if Rice was damned with faint praise as a “nice man” and a “good writer,” but an innocent one, Mr. Congdon argues on behalf of his “resolve to elevate rather than depress the human spirit.”

Take Babe Ruth. The two were friends for three decades, so Rice knew all about the womanizing, the drinking, the other indulgences of “our national exaggeration,” as one writer of the Aw Nuts school described him. He chose instead to focus on what Ruth did and meant for “the kids, the cripples, the heart-weary, and the underprivileged,” as he wrote in a 1948 column as Ruth was dying of cancer.

And then there’s the fixed World Series of the 1919 Black Sox scandal, which nearly killed the sport. Ruth’s heroics on the diamond saved baseball. The nation needed him.

When Ruth died, Rice paid tribute to him in verse, as was his tendency: “Game called by darkness — let the curtain fall. . . . The Big Guy’s left us with the night to face, / And there is no one who can take his place.”

Another era gone.