Greatness in Waiting

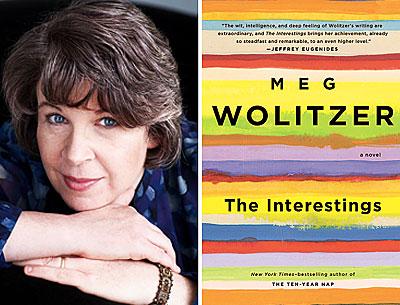

“The Interestings”

Meg Wolitzer

Riverhead Books, $27.95

In the summer of 1974 Julie Jacobson, a 15-year-old self-proclaimed outsider, arrives at Spirit-in-the-Woods, a summer art camp in Belknap, Mass. A “shy, suburban nonentity” from Long Island, where she lives with her recently widowed mother and older sister, Julie longs for something other than the anonymity and world of freaks that she believes she is doomed to inhabit. When she is unexpectedly drawn into a group of five New York City teenagers at the camp, she finds with them a “small packet of happiness.”

The group consists of the beautiful and sensitive Ash Wolf and her arrogant and handsome older brother, Goodman; the ugly creative genius Ethan Fig; Cathy, who lives to dance, and Jonah, the strikingly handsome son of a successful folk singer who possesses his own musical gift. The six name their group the Interestings, a name meant to carry a good deal of ironic weight, but for Julie the name has the utmost meaning.

Her new friends and the lives they live (or the lives she imagines they live or will live) enthrall her. They are her best chance of escape from the geographical and intellectual wasteland of suburbia. Because of her friendship with them, she believes she is a different person when she leaves camp at the end of the summer. Her transformation is validated in her name change to Jules, which Ash bestows on her.

So begins a lifetime of friendships and messy entanglements that Meg Wolitzer traces for the next 30 years of their lives in “The Interestings,” her rewarding new novel about love, marriage, friendship, family, and talent.

At Spirit-in-the-Woods the six friends seduce themselves and are seduced by the promise of greatness or “greatness-in-waiting.” They all see themselves as artists of one kind or another. However, it is Ethan alone who stays true to his early promise and develops a cartoon concept into the small media empire of “Figland,” an animated television show that he creates, writes, and does voices for. Ash remains artistically involved as a theater director, although how much her success is due to her talent and how much to her social and financial situation is uncertain.

Jonah abandons his musical talent and denies himself when a fading folksinger takes advantage of the young boy’s gift and imagination. Cathy’s dreams of being a dancer are betrayed by her body type. Goodman wants to be an architect, but he shows no aptitude for it. (He and Cathy become the most removed from the initial group — and from much of the story — because of a tragic scandal and its aftermath that links them.) Jules, who moves to New York City after college, briefly struggles to be a comedic actor but reluctantly accepts that she does not have the necessary talent. This failure, or sense of entitlement denied, haunts her for much of her life.

Ms. Wolitzer thoughtfully explores the notion of talent and creativity, of how some embrace it and are defined by it while others abdicate their talent because it is too much of a burden, and still others yearn for a creativity that will never be theirs while ignoring that which is theirs to nurture and develop.

Jules is the primary axis around which the story is told. She sees herself as the perennial outsider looking in. Her position on the periphery of Ash and Goodman’s family is the closest she ever expects to experience “a cultured, lively family that celebrated everything.” She thinks them vivid, alive, and desirable, while her mother and sister are perceived to live small and quiet lives in the suburbs, jealous of her tentative attachment to the Wolfs’ cosmos. Unable to escape her “craving for a big life,” Jules experiences a persistent sense of loneliness, of not belonging, even after her marriage to Dennis and the birth of their daughter, Aurora.

Ash and Ethan unexpectedly marry and become the “big-deal couple” by which Jules measures her own disappointment and envy. She sees in them, as she saw in the Wolf family, the life she believes she desires if not deserves. She is seduced (and deceived) by what she sees their lives to be — never seeming to recognize Ash and Ethan’s own problems and disappointments, both individually and as a couple, not the least of which is Ethan’s lifelong desire for Jules, his true soul mate.

Constantly comparing her life — her husband, their apartment, their jobs, their bank account — with that of Ash and Ethan, Jules finds the difference between her life and that of her friends “humiliating” because of Ethan’s artistic and commercial success. In her eyes the Wolf family and then Ash and Ethan “could do no wrong.” And she continues to see much of her life with Dennis as small and sad compared to that of Ash and Ethan. Even Aurora suffers in comparison to Larkin, Ash and Ethan’s daughter. In her mother’s eyes, she is “not stellar like Larkin,” who is also easier to love.

Jules, however, is lucky in having Dennis as her husband. Although he suffers his own heavy burden (and Jules, to give her credit, never truly wavers in her support of him), he freely accepts his averageness and clearly sees their friends as flawed, ordinary people rather than the near demigods that Jules continually sees. Dennis recognizes his wife’s faults, even indulges them, as he waits for her to “get over herself.” They are both even luckier in their daughter, who may be the most well adjusted character in the story.

Against the backdrop of many of the social and historical touchstones of the last quarter of the 20th century — AIDS, Watergate, autism, the Unification Church and the Moonies, child labor exploitation, 9/11 — Ms. Wolitzer deftly and subtly weaves a rich tapestry from and through her characters’ lives as she explores the complications of love, family, and friendship. There is tremendous depth and emotional richness to all of the characters, making them extremely believable. They are handled with intelligence, warmth, and wisdom — the reader is drawn into their stories.

Ms. Wolitzer could have easily held almost any one of them up to satire and cruel humor, but she refuses to do so. She provides instead thoughtful and compassionate portraits of human characters with all their faults and disappointments allowing them to come alive as touchingly real. They are not always likable, especially Jules, but there are no simple heroes or villains here. The characters are fully formed with a complex and nuanced reality.

In a fairer world Meg Wolitzer — a writer of consistent clarity, grace, wisdom, and wit — would enjoy greater recognition as being among the best writers of her generation. Here is hoping that this wonderfully accomplished novel, which reads much shorter than its nearly 500 pages, will help bring to her the larger audience and wider acclaim she deserves.

William Roberson taught literature at Southampton College for 30 years. He now works at L.I.U. Post and lives in Mastic.

Meg Wolitzer is a frequent visitor to her family’s house in Springs. She teaches in the M.F.A. program in creative writing and literature at Stony Brook Southampton.