GUESTWORDS: Boom-Boom Warms Up

Surfing the Net recently, I finally figured out what’s gone wrong with baseball. The cheapest seat at an upcoming Yankees-Red Sox series was $55, about four times the cost of an official major league baseball, which goes for $13.99. In my baseball days, back in the 1930s, the cost of a baseball was four times that of a bleacher seat, about a dollar for the ball, 25 cents for the ticket, and only 10 cents for kids under 12, which is what my friend Dick Warren and I were in 1937, when Boom-Boom was pitching for the San Francisco Missions.

Now I do concede an element of apples and oranges here in that the Missions were a “minor” Pacific Coast League team. But then the perks we got for our 10 cents more than made up for the variations in league status. There was Ball Day when the players stood on platforms and tossed baseballs to the kids to scramble for, hundreds of baseballs, and some pretty good fights broke out in the pileups that followed. Imagine what the lawyers, insurance companies, and today’s fretful parents who ring their kids’ cellphones every 15 minutes they aren’t home would say to that one.

Dick, who was the smaller, nimbler, and more daring of us, got four balls on one afternoon. And then there was Bat Day, when we’d get autographed Louisville Sluggers. Real bats with autographs no player would think of asking money for.

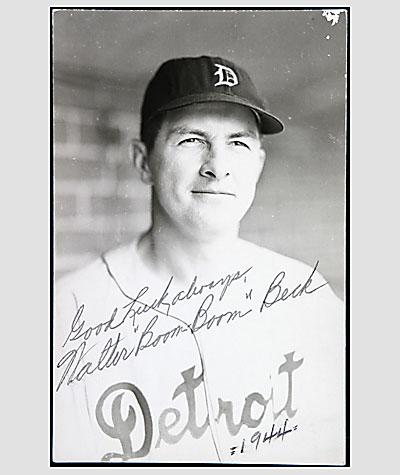

The most important perk of all, however, was that we got to hang out with Boom-Boom. Boom-Boom was Walter William Beck, a relief pitcher for the Missions from 1935 through 1938. An Internet photo shows a gangly young man with an innocent country-boy Jimmy Stewart look that masks the sophistications of hot-rod racing under the torrid sun and torrid nights making out in the back seat of a borrowed Airflow Chrysler.

The 10-cent right-field bleacher seats came right down to the field level, where in the narrow foul space between the diamond and the stands the Missions’ pitchers warmed up (not protected girly-boy bullpens in those days). When the Missions were behind 10 to 2, as they often were, Boom-Boom, a sidearm spitballer, would be called upon to go in and finalize his team’s humiliation. He’d saunter out of the dugout to warm up and Dick and I would clamber over the bleacher seats to the front field-level row, where he would pause long enough to give us chewing gum, in lieu of the chewing tobacco Dick requested, inform us that the country was so messed up it should be given back to the Indians, and tell us that his present objective was to get Ted Norbert, left fielder for the rival San Francisco Seals, to hit an infield pop-up so high the center fielder would have time to meander in, yawn, and catch the ball. Norbert, who succeeded Joe DiMaggio in the Seals’ outfield, had a talent for hitting stratospheric pop-ups that I believed could bring rain.

Dick and I illusioned ourselves into believing that we had christened Beck Boom-Boom from our appreciation of the resounding sound that line drives hit off him would make smashing into Seals Stadium’s wooden fence. But now I learn the moniker preceded us.

Here’s how it really happened. On July 4, 1934, Beck was pitching for the Brooklyn Dodgers and leading in a game against the Philadelphia Phillies when the Philadelphia batters started to blast him. The Dodgers’ manager, Casey Stengel, went to the mound to remove him and asked him for the ball. Beck said he still had good stuff and refused. Stengel demanded the ball. Furious, Beck fired the ball from the pitching mound all the way to the tin-plated right-field fence, where it boomed hugely and caromed back toward Hack Wilson, the Brooklyn right fielder.

Wilson, a prodigious hitter and drinker, was hung over, and more than somewhat abstracted from events on the field. Assuming the boom was yet another long line drive off Beck, Wilson sprung awake, chased down the ball, and fired a perfect throw to second base. Beck left the game and, at the end of the year, with a two-win, six-loss record, left the majors for the Missions, where he entered our lives.

To our astonishment, Boom-Boom actually returned to the major leagues in 1939, where, appropriately, he pitched during World War II for the Phillies, who, probably the most inept team in major league history, lost more than 70 percent of their games over the next four years. Beck did little to lift them, losing about 75 percent of his games. He returned to the minors and pitched his last game, for the Toledo Mud Hens of the American Association, in 1951 at the age of 46, and won it 10 to 2. He died in 1987 in Illinois.

Dick and I went off to war. I was lucky and made it back okay, but Dick was killed in 1945, in the Huertgen Forest. We’d have done a lot of things together if he’d lived, but we’d never have spent any time in $55 bleacher seats with no access to a bullpen.

Richard Rosenthal is the author of “The Dandelion War,” a humorous novel about class warfare in the Hamptons, and the host of “Access,” which won an award from the Alliance for Community Media in 2010 for the quality of its non-mainstream broadcasting. He lives in East Hampton.