Hardscrabble Truths

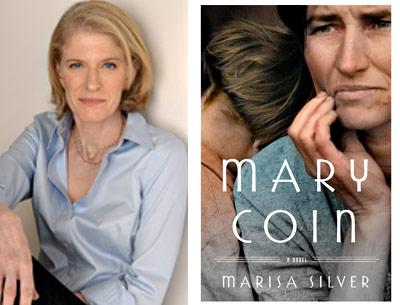

“Mary Coin”

Marisa Silver

Blue Rider Press, $26.95

If, as the popular wisdom holds, a single picture is worth a thousand words, then it is not entirely surprising when an iconic photograph inspires a novel of some 325 pages. Neither is it surprising when, in the hands of a gifted writer, the resulting novel is a small masterpiece.

Employing as her jumping-off point Dorothea Lange’s Depression-era photo “Migrant Mother” — a commonplace in American culture, as well as in the annals of photographic history — Marisa Silver creates not one but three fictional back stories and deftly brings them to intersect at moments of maximum impact. In the process, Ms. Silver impels her reader to consider what it means to look, what it means to see, and what it means to know about life in the deepest, most essential way we call truth.

The primary story in this book is that of the woman in the photograph, Mary Coin herself. We follow the arc of her life from girlhood in a poor Oklahoma town (before the dust storms came) to old age and impending death in north-central California many years later. It is a mean life, particularly as the Great Depression’s noose of poverty and scarcity tightens around Mary and her seven children, her first husband having died not long after the Coins made their way to the elusive paradise of the Golden State. (“Mary sustained the weight of sorrow that would descend on her freshly each morning and had to remind herself all over again that her husband was gone.”)

It is during the long period of struggle as an itinerant picker of produce in the Central Valley that Mary encounters another female itinerant — the photographer Vera Dare, who, under the auspices of a (New Deal) government program, travels the country, collecting documentary images of how people are suffering under the dire economic circumstances of the period. With a little coaxing, Mary agrees to be photographed by Dare, neither woman imagining the implications over time of that short-lived encounter. (Vera doesn’t even ask her subject’s name before or after she takes her picture.) Nor does either of them glimpse that their lives have anything in common — which, over the course of the novel, we come to understand they do.

The third narrative thread of this novel is that of Walker Dodge, a present-day professor of social history whose expertise is in combing through the records and tangible ephemera of the everyday lives of people in bygone eras, in order to gain an authentic understanding of what those lives, and those periods, were like. When Walker applies his professional skills to questions about his own family’s history, the hitherto disparate tales of the three primary characters begin to form a skein of connectivity.

One of the overarching themes of this novel is how complex relationships can be between parents and their children. In all three of her central characters, Ms. Silver illustrates that an absence of conventional sentimentality is in no way indicative of a weak bond between a mother or father and her or his sons and daughters.

Among the great strengths of Ms. Silver’s writing is how astutely she observes and describes so many aspects of life. Of the hardscrabble poverty and escalating ill fortune of the Coin family, she writes, “They had never had anything but now they had nothing.” Of Vera Dare’s work as a society portrait photographer in San Francisco before the Depression, she tells us that Vera’s clients often referred to her as “my photographer . . . as if Vera were part of a retinue . . . my driver, my girl at Gump’s.” And of so much of America in the 1930s, she says, “The whole world had been abandoned.”

The missions of the photographer and the historian are close to the core of this moving story; each in his or her own way seeks truth. As soon as Vera takes the photo of Mary that would make her famous, she “felt in her gut as though there had been a sudden synchronizing of all the heartbeats in the world. . . .”

Of his particular work, Walker believes, “The present provides neither the gentling amber light of nostalgia nor the bright possibility of hope.” Moreover, “Everyone wants to be known. Perhaps the ones who conceal themselves most of all. The question is: Who is foolhardy enough to go in search of them?”

The implicit answer, of course, is academics such as himself. By extension, however, it feels as though Ms. Silver is also responding, novelists such as herself and the readers they bring along on the search.

When, toward the end of the book, Walker grasps the truth that causes everything to fall into place, he “knew that life was a set of extravagantly enacted delusions to mask the fact that all the relied-upon verities were meaningless.”

Nevertheless — or perhaps for that very reason — we, as thinking human beings, continue to seek understanding.

If one wished, it is possible to discover, in the stories of Mary and Vera, reflections of the lives of Lange and Florence Owens Thompson, the actual subject of the photographer’s celebrated photo for the Farm Security Administration. To do so would be beside the point, though. However meticulous her research, Ms. Silver has chosen to use “Migrant Mother” as merely a trigger to the imagination, creating a fictional universe, a made-up series of events, and imaginary lives that are most meaningfully appreciated in their own light.

Filled with humanity, this novel takes its place beside the likes of John Steinbeck’s “The Grapes of Wrath” and James Agee and Walker Evans’s “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.” Like those works — indeed, like the Great Depression itself — it touches us deeply and leaves us with a haunting sense of being changed forever. In the final analysis, isn’t that what successful literary fiction does best?

To conclude on a personal note: As many times as I have seen the Lange photograph and as well as I thought I knew it, Ms. Silver’s novel demonstrated to me that an essential element of the picture, critical to her story, is something I had never before noticed. That is why we revisit classic pieces of art (and that includes literature): There is always something more to learn.

A weekend resident of East Hampton, James I. Lader regularly contributes book reviews to The Star.

Marisa Silver, who lives in Los Angeles, has been a regular visitor to East Hampton, where her parents had a house for many years.