In Harms Way at East Hampton's Drawing Room

Robert Harms makes paintings you want to inhale, lie beside, wallow in. In a little cottage on Little Fresh Pond in Southampton, he bides the time, season by season, absorbing his surroundings through eyes that transmute the air and landscape into a distillation of time and place.

His paintings used to be made of thicker stuff, more in keeping with Joan Mitchell’s typical density, which no doubt came from his work as her studio assistant and his role as protégé. In more recent years, he has revealed far more white on his canvases, rarely ending his compositions anywhere near the stretcher and thinning his paints to let the white show through. This makes them airier and seemingly backlit, even when paintings such as “Snow” or “Beech Trees,” both from last year, are predominantly gray.

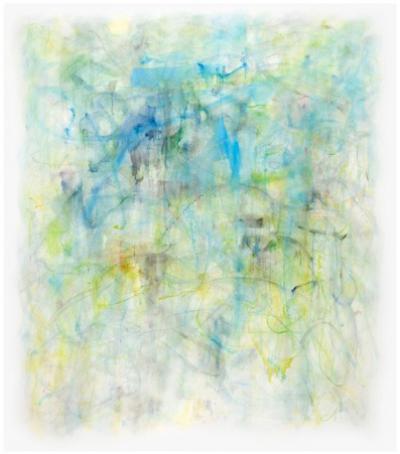

The newer paintings, on view at the Drawing Room in East Hampton, are smudgier over all than his other recent work, and the gallery helpfully provides a few works from a couple of years ago to show the progression. From the calligraphic lines and ribbons that dominated his work for a while, he is progressing back toward a murkier surface, even if it continues to have a sheerness of application.

There is also a sense of travel and variety in his newer subject matter. He was never completely tied to Little Fresh Pond, although it dominated much of his work of the past decade. His bright tropical floral studies, shown in other exhibitions, or titles like “Toward the City” from 2008 or “110 Old Stone Highway” from 2010 are earlier examples of off-topic works.

Here, we have “Garden Visits” from 2012, “Noyac” from last year, and “Different Landscape” from this year. The last one is a departure in more ways than one. It is mysterious and compelling, leaving much more to the imagination than anything he painted recently. Mr. Harms often titles his works with times of the year when he is not being more specific about the objects, like beech trees, he is portraying. In this case, it is difficult to discern whether the vantage point is from above, below, or across the horizon.

Is it different because it is finally spring and the first spring colors of green and yellow, made more striking by a deeper blue sky, are apparent? It’s not clear. The white wash, which now overtakes any color underneath, is certainly different, and the viewer must strain to see the subtle shifts taking place there.

In “Beech Trees” too, the subject is so faintly suggested, and yet the trees are there, their trunks, branches, and even the leaves not too far removed from the sweeping stain that blurs the lines that were once so present and vivid. It is rather radical to see him treat oils this way. Their rich intensity, usually reserved for a more substantial application, has been thinned, brought down to the wispiness of watercolor and the powdery messiness of charcoal and pastel.

If one veers toward the poetic in describing this artist’s work, it is because his is an art of sensation and feeling. “Snow” replicates the experience of seeing the varied colors in layer after layer of the ostensibly white stuff as time and light transform it, sometimes moment to moment.

Even if you have never stood beside the pond, he can communicate its varied presentations of shadow and hue, through winter’s icy floes and summer’s crowded vegetation. He can pull those who have never swum in it under the water to examine the refracted texture of the verdure and sky around it.

There are seven paintings in the show and only five in the main room. The others — “After Winter” from 2012 and “Morning Lilies” from 2011 — are in the window and office respectively. They are plenty. The large canvases fill the walls they inhabit with their content, and the generously allotted white space between them lets them breathe and allows us to appreciate their subtleties of color, light, and shadow.

The exhibition is on view through June 1.