Heaven and Scorched Earth

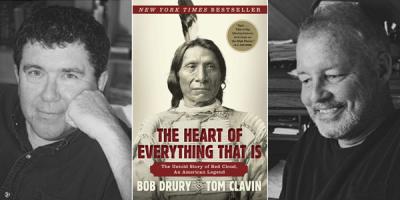

“The Heart Of

Everything That Is”

Bob Drury and Tom Clavin

Simon and Schuster, $30

“The Heart of Everything That Is: The Untold Story of Red Cloud, an American Legend” is an inspired achievement. The authors Bob Drury and Tom Clavin have dug deep into contemporaneous newspaper stories, eyewitness accounts, military records, and a long-lost autobiography dictated by Red Cloud, “the only American Indian in history to defeat the United States Army in a war, forcing the government to sue for peace on his terms.”

The Sioux warrior’s accomplishment puts Custer’s subsequent last stand in perspective — a military victory, for sure, but one made possible through Red Cloud’s leadership, intertribal diplomacy, and military strategy, all of which broke from longstanding Indian tradition.

The Battle of Little Big Horn followed by a year the Battle-of-the-Hundred-in-the-Hands (the name coined by a hermaphrodite seer), during which a combined force of Lakota, Oglalas, Brules, Miniconjous, and Sans Arcs Sioux joined with their former enemies — Cheyenne, Arapaho, Nez Perce, and Shoshones — to massacre 81 soldiers they had drawn out of Fort Phil Kearny in northern Wyoming in June of 1866.

The fort was meant to protect gold miners, white hunters, and settlers heading west on the Bozeman Trail. The Bozeman was a northern extension of the Oregon Trail and wound through prime Sioux hunting ground. And, it abutted the Black Hills of South Dakota, the Sioux’s sacred Paha Sapa, the heart of everything that is.

The depth of research and page-turning strength of narrative bring the reader back in time to take the Hollywood out of the picture and give an unflinching portrait of Indians and whites alike. For the Sioux, Paha Sapa was heaven on earth at the time, or close to it: buffalo as far as the eye could see, fresh streams from mountain snowmelt, cool forests, oceans of grassland, fish and game abounding.

The authors point out that while Sioux culture possessed what might today be thought of as a higher consciousness about their relationship to their environment, it did not extend to a willingness to share it. The Sioux and most of the Plains Indians at the time were warriors who put great store in protecting their territories, and in the process killing, torturing, and humiliating their enemies — other tribes and white settlers — before, during, and after death.

“The Indians are desperate; I spare none, and they spare none,” Col. Henry Beebee Carrington wrote in a dispatch he knew might not make it to the telegraph at Fort Laramie to the south. He was begging for reinforcements after realizing that nearly all of Fort Phil Kearny’s defenders — they had been suckered out to fight Crazy Horse and over 1,000 Indians — would not be coming back, or would be brought back, “like hogs brought to market,” scalped, disemboweled, beheaded, gelded, and sodomized with spears.

In the final minutes of the battle, “Captain Brown was still standing, surrounded by an orgy of butchery . . . [he] had one cartridge left in his revolver. He put the barrel to his temple and pulled the trigger.” The Sioux were playing for keeps.

It is the authors’ explanation of why the Sioux were playing for keeps that is most enlightening, reasons that meant virtually nothing to people back East, especially in the wake of the Civil War. Was it any wonder that Gen. Phil Sheridan, who took the scorched-earth approach during the Civil War — and who coined the expression “the only good Indian is a dead Indian” — was chosen to push the Sioux onto a reservation after gold was discovered in Dakota’s Black Hills, right in “the heart of everything that is”?

In addition to the scholarship that went into this book, the authors should be hailed for their careful description of the times. These were hard, tough people, Indians, soldiers, and settlers alike. We meet buffalo hunters and mountain men like James, Old Gabe, and Bridger, half-breed scouts and translators, cowboys, mule skinners, and Crazy Horse, whose daring rides appeared as though he possessed supernatural immunity to bullets. We meet Young-Man-Afraid-of-His-Horses and the Cheyenne Dull Knife.

And, of course Red Cloud, who began life as a hot-tempered orphan but who was able to rise through the hierarchy of Sioux and intertribal leadership by way of his intellect rather than brute force alone. He was a fighter who harnessed guerilla strategy and terror to overcome an army that had just won the War Between the States, and he was the man who realized, before Custer lost his scalp, that resistance was futile.

Wagon trains endured insufferable heat in summer, brutal subzero temperatures when the snows came, and no shelter except for what could be hewn by hand or, in the Indians’ case, by animal hides and ancient tradition. And then there were the horses, their immeasurable value. Nothing moved without them, and they lived and died hard. We are given the story of the amazing horse that delivered Colonel Carrington’s desperate dispatches through a blizzard and subzero temperatures, but you will have to read it for yourselves.

We meet soldiers battle-hardened by the Civil War, many who were brave, some fatally overconfident. There were the weapons: arrows loosed by expert bowmen versus outdated muzzle-loaded guns. But then came canon and grapeshot, repeating rifles, Colt pistols, and, finally, the railroad.

Philosophically, it was a case of an unstoppable force meeting an immovable object, at least at first. There was a right of it, and a wrong of it, and some in Washington realized the difference at the time.

But there was also the momentum of Manifest Destiny, the idea that the people of the United States had a moral duty to “tame” the West by displacing or exterminating its native inhabitants. It seems maddeningly cruel and ignorant by today’s standards, although modern societies, here and everywhere, apply virtually the same arrogance to the squandering of natural resources, plants, and animals.

In many ways, “The Heart of Everything That Is” is just that.

Bob Drury and Tom Clavin’s previous books together include “The Last Stand of Fox Company” and “Halsey’s Typhoon.” Mr. Clavin lives in Sag Harbor.