High Achiever

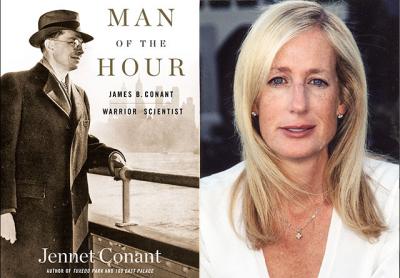

“Man of the Hour”

Jennet Conant

Simon & Schuster, $30

The only element I might question in Jennet Conant’s new biography of her grandfather James Bryant Conant is the title. “Man of the Hour” does inadequate justice to the lofty accomplishments of Mr. Conant, not to mention the span of time during which his influence was felt. But perhaps I quibble.

Over the course of a lifetime that lasted just short of 85 years (1893 to 1978), Mr. Conant established an early reputation as a brilliant chemist, headed a unit of the Army’s chemical warfare division during World War I, served as the president of Harvard University for 20 years, was one of the leaders of the Manhattan Project, which developed the first U.S. nuclear bomb that brought World War II to a conclusion, and served as the American high commissioner for Germany during the early Cold War years. Among other things.

By just about every measure, Mr. Conant’s was a life of significant achievements. He brought a flinty New England competence to everything he tackled. His granddaughter, a New York Times best-selling author, brings comparable skill to the potentially tricky task of recounting that life.

Family standing mattered tremendously in the Boston of Mr. Conant’s birth. His own family was second-tier, at best. Rather than arriving on the Mayflower in 1620, the first Conant to reach America came on the sister ship Anne in 1623. Instead of residing in fashionable Back Bay or Beacon Hill, the family made its home in old but plainer Dorchester, and young Jim Conant graduated from the local Roxbury Latin School, not from one of the traditional boarding schools where most Harvard students of the day prepared for college.

Upon entering Harvard College, however, his academic prowess distinguished him. College was followed by graduate school, also at Harvard, and he obtained a Ph.D. in chemistry in 1916. After a brief stint in private business in Queens, Mr. Conant entered the military during World War I, where his training was put to good use in the then-new field of chemical warfare. (“The war . . . made stars of organic chemists.”)

Following the armistice of 1918, Mr. Conant joined the chemistry faculty of his alma mater. He married Grace (Patty) Thayer Richards, daughter of a famous Harvard chemistry professor and chairman of the department. He gained not only a devoted wife, but also a powerful mentor in his father-in-law, though no one ever seems to have argued that Mr. Conant’s rise at Harvard was anything but well deserved.

His appointment as Harvard’s 23rd president, in 1933, was exceptional not only because Mr. Conant was the youngest person ever to assume the position, but also because it was rare for the president not to have come from Boston’s firmly entrenched social elite (which included his wife’s family).

Leading America’s oldest university was a daunting task; Harvard was tradition-bound, to say the least. Mr. Conant understood the need for the institution to cast a wider net, in an effort to attract the best students and most brilliant faculty members, regardless of their social backgrounds, in order for “Harvard to become a truly national university.”

Educational reform and the democratization of education were priorities of Mr. Conant’s throughout his life. He pursued these goals less as a highly visible crusader than as a quietly persistent statesman.

Unlike how such matters would play out today, Mr. Conant remained at the helm of Harvard throughout the most attention-worthy chapter of his life, which coincided with the period of World War II and its aftermath. This time, the warrior scientist occupied a position of top leadership. The saga of the development of the nuclear bomb is a tale of intrigue, suspense, setbacks and triumphs, political machinations, and moral quandaries.

As chairman of the National Defense Research Committee, Mr. Conant was among the most highly placed civilians in the development and deployment of the first nuclear bombs. He is described as a thoughtful, tactful, principled administrator who earned the confidence of American presidents from Franklin D. Roosevelt to Lyndon B. Johnson.

When it came to the Manhattan Project, Mr. Conant did what needed to be done, in the interest of bringing the war to an end. He was, nevertheless, deeply mindful of the cataclysmic potential of what had been created. “While Conant cautioned against ‘fear, panic, and foolish, short-sighted action’ in his public speeches, privately he was wrestling with his own post-atomic jitters.” In 1946, after giving the matter careful consideration, he turned down President Truman’s offer to become the first head of the Atomic Energy Commission.

One forgets, reading this biography, that the author is a direct descendant of her subject. (Clearly, we have here a biography, not a memoir.) That is as it should be. Ms. Conant remains a dispassionate observer of Mr. Conant’s life. In a carefully researched and thoroughly annotated work, she needs only to report. There is no real synthesis, nor does there need to be. Mr. Conant’s life and multifaceted career speak for themselves. Though he worked very hard and applied himself with proper Yankee diligence to every assignment and challenge, he did not have to struggle to succeed. He was good.

Thus, this is a work of history as much as biography. As an account of the scientific research and development that were the underpinnings of both World Wars, it is outstanding. Add to that the description of nuclear politics of the 1940s and beyond (both domestically and internationally), and you have a book that makes an important contribution. (The descriptions of the career of J. Robert Oppenheimer, head of the Los Alamos Laboratory and one of the “fathers of the nuclear bomb,” inspire me to refresh my awareness of that particular story.)

I should note that one advantage that the author brings to bear here, as a direct descendant, is her understanding of the one area of Mr. Conant’s life that was less successful than the others — his home and family life. Things were not easy. Patty Conant was a deeply nervous and anxious person. Those tendencies ran in her family. (Both of her brothers committed suicide.) Moreover, the Conants’ two sons found their father lacking on numerous occasions. To her credit, Ms. Conant does not demur when it comes to reporting on these aspects of her grandfather’s story. The result adds to an honest and balanced examination.

Although he appeared multiple times, over the years, on the cover of Time magazine, James B. Conant’s name has faded from most people’s awareness. Jennet Conant’s first-rate volume about him should help reverse that phenomenon.

A weekend resident of East Hampton, James I. Lader regularly contributes book reviews to The Star.

Jennet Conant lives part time in Noyac.