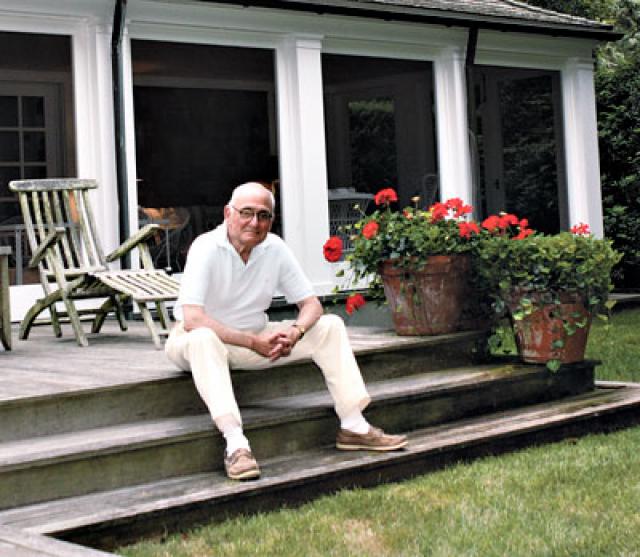

At Home in East Hampton

The dean of Yale University’s School of Architecture lives on a well-traveled road north of the highway in East Hampton, next door to a construction site where, after his attempt to buy the lot fell through, a nondescript house is going up. His own house, still modest at about 2,000 square feet after extensive renovations, began life as a run-of-the-mill ranch. “I bought a three-room house at a fiscally deprived time, in 1978,” he said. “It was a nothing house. I kept thinking, this will be a halfway moment and then I’ll move on. But houses kept getting ahead of me, pricewise.” He let things stand for a few years until one day, working in the garden out back, the famous architect heard a shocked voice exclaim, “Oh, my god! He lives THERE?” He yanked his “Robert A.M. Stern” sign right out of the ground and began the makeover soon after. Bit by bit over the next decade, red cedar shingles replaced the 1930s white siding, a gabled roof and a second-floor tower with a guest bedroom and bath was added, French doors opened up the no longer small or dark rooms to the outdoors, and a Stern trademark, a big screened porch reminiscent of the ones on the old summer colony cottages, pulled it all together. The house has ceiling fans rather than air-conditioning, and a short driveway, no garage, where a sporty red BMW Z4 with the license plate RAMS 7 (1 through 6 were already taken) has pride of place. In a 1993 before-and-after critique for Architectural Digest, Paul Goldberger wrote that Mr. Stern had not turned his vacation home into “one of the rambling shingle-style houses that have made him famous — he knows better than to coax this structure into more than it is capable of — but it is full of references to these houses.”And 21 years later it is still, as Mr. Goldberger put it, “just the tiniest bit too grand for its situation.” Which troubles its owner not a jot. “I like it here,” he said recently during an unaccustomed work break. Mr. Stern does not use a computer or email, and there is spotty or no cellphone service on his road. “No cell is fine,” he said. “I like people to do things for me.” He did admit to a TV set, but only to run DVDs of old and new movies and mysteries. “I’m a busy guy. No time to watch TV.” The author of half a dozen books and innumerable scholarly articles, Mr. Stern works anywhere in the house, or at a pergola out front. “The chairs are uncomfortable, which is good, it keeps me awake.” He is just now finishing up a history of the Yale School of Architecture, which will be 100 years old in 2016. The manuscript is due next month. He doesn’t manage to get here much anymore, even in the summer — “The horror of driving out!” — but when he does come, he said, “I stay in my little corner. The traffic is so bad, I almost never go anywhere outside the village.” “Ironically, I am not a beach person,” he said, though he called Main Beach the village’s “great public space, an amazing asset. Sometimes I do the Bonacker thing at 5 p.m. I sit in my car and look at the beach. I think after a certain age you should never be seen in public unless fully clothed.” Mr. Stern, who early in his long and distinguished career called his architectural style “postmodernism” but now describes it as “modern traditionalism,” has put his stamp on buildings all around the world — public libraries, courthouses, banks, skyscrapers, museums, and thousands of award-winning private residences, among them many on the South Fork (one of which, in Montauk, was his first commission anywhere). Closer to home, he designed the new Town Hall complex and a notable addition to Guild Hall, and worked with Randy M. Correll, one of his partners, who designed the much-acclaimed children’s wing of the East Hampton Library, opened earlier this summer. He is currently completing designs for two new residential colleges at Yale — “one of the great architectural privileges of my career,” he told The Yale Daily News when the commission was announced. Construction of the new buildings, which will look, Mr. Stern said succinctly, “like Yale colleges,” is to begin in January. Thirty-two years ago, in a scholarly but eminently readable treasure of a book called “East Hampton’s Heritage” (now, sadly, out of print), Mr. Stern wrote that architects who respected “the temper of the place” had shaped the village’s summer colony buildings. “I think there are a few too many modern houses here,” he said, but even today, despite the cars and the crowds and the overbuilding, he maintains that the temper of the place has not changed. Not, at least, “in the sense that we still value the old 17th and 18th-century architecture. Very few towns have such a rich collection of these early houses. People added on to them, but they didn’t tear them down.” And, he said, the wealthy New Yorkers who discovered East Hampton in the 1880s and ’90s “built new houses like the old houses” and “kept the landscape how it was meant to be . . . open lawns, no hedges.” Southampton, by contrast, “even by 1903, was filled with hedges.” Mr. Stern is not a fan of hedges. Open spaces are a different story. “In any village you need public space,” he said. Here, besides the beach, “we have the green, a beautiful visual relief rimmed by traffic. Also the Nature Trail. And Hook Mill.” He particularly likes “the idea that you can drive up Newtown Lane and at one point, all at once, you’re out of the village” and onto the relatively wide-open Long Lane, surrounded by fields — “except for the abominable, overscaled, hideous high school. It should have been in the woods.” The architect and his ex-wife first came here in the late ’50s, when, he said, “box-like houses were being built, perched on pilings in the Sagaponack potato fields — not at all site-specific. Charley Gwathmey set a trend for sculptural composition, houses as objects divorced from the landscape — nothing to do with place.” (Pilings, he insinuated, may be okay on the beach, like sandals, but put them down among potatoes and you have sandals with socks.) “You could bike around East Hampton then and see the houses. There were no hedges. So, I got interested in the changes and decided I wanted to build some of these houses myself. Clients wanted mod cons, but houses with character — shingles, molding, details, screened porches. The screened porch is an American, neglected, thing.” “I like to pick up on old traditions and carry them forward into the future” — meaning, as he once explained to a New York Times interviewer, “modern in their layered complexity, modern in their openness to the out-of-doors, and above all modern in their free, eclectic spirit.” It was not always so. “Once,” he said reflectively, “we built — imitated — shingled houses. I still think we do them best. In fact, I know we do them best!” Only one of the residences he has designed here has been demolished, Mr. Stern believes. “We tore down one house ourselves, in Quogue, and designed a new one on the site. It was a small house in bad condition; it had to go. I miss it.” He paused a minute, thinking, and suddenly remembered another. “The house I designed for Billy Joel and Christie Brinkley, a huge renovation. Jerry Seinfeld tore it down — and the architect who did it used to work for me! A bitter pill!” He often speaks in exclamation points. Once upon a time, “very early on,” Mr. Stern was front-and-center on the sites of his projects; now, he almost never supervises. “I like to design them, to see them unfold, to visit from time to time. I am friends with many clients, so I get to go over for a meal and see.” “But my partners” — Roger H. Seifter, Grant F. Marani, Gary L. Brewer, and Mr. Correll, who lead the residential practice at Robert A.M. Stern Architects, known as RAMSA — “really concentrate on supervision. So anyone who wants to have me is lucky. I have a hand in everything, but I turn over responsibility more and more to my partners.” The partners were at the East Hampton Library two weeks ago to talk about their new book, “Designs for Living,” a handsome showcase of their work here and elsewhere, published by Monicelli Press in May. The four, who have been with RAMSA for between 25 and 40 years, were as one in their admiration for and devotion to the boss, whom they agreed was blunt, remarkably keen about people, and a terrific organizer. They are working on a house in East Hampton now, “the first one in the village in a while,” Mr. Stern said. Pressed for details, he said it was off Main Street; further than that he would not go. U