How Barbra Changed Our World?

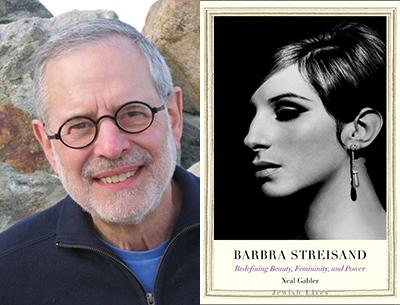

“Barbra Streisand”

Neal Gabler

Yale University Press, $25

Miss Minnie Rosenstein had such a voice so fine

Just like Tetrazzini

Any time that Minnie sang a song

You’d think of real estate seven blocks long

Some song!

— “Yiddisha Nightingale,” c. 1911 by Irving Berlin

The New York City Board of Education, in its infinite wisdom circa 1955, divided a long-established school district in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn to create banjo-shaped Wingate High. Had it not, I would have gone to legendary Erasmus Hall and been a classmate of the soon-to-be famous Barbra Streisand. But would I have noticed?

As this brief and sometimes rapturous new analysis by the culture critic and author Neal Gabler reminds us, Barbra was then a mostly unmemorable mieskeit — Yiddish for ugly duckling — skinny, slightly cross-eyed, teased and tormented, or so she recalls, despite plenty of other prominent Jewish noses among her peers.

She was even turned away by the school’s choral club, then stashed in the rear and denied any solos, though singing on the stoop of her apartment house had gained her applause from neighbors since she was a tot.

The closest I got was a few years later, in the early 1960s, at a small Greenwich Village restaurant, sitting just a table away from Ms. Streisand tete-a-tete with Elliott Gould, her castmate in the musical “I Can Get It for You Wholesale” on Broadway, later her husband, and still later her ex, but already outshone by her dynamite debut as “Miss Marmelstein.”

As she grew more famous, less “notice me” kooky, I bought her records, of course. But my greatest appreciation came 20 years later after dubbing tracks from her “People” album onto a cassette that had space left from the first of three unexpected albums of Great American Songbook tunes by the pop-rock queen Linda Ronstadt with Nelson Riddle (“What’s New,” 1983).

Playing it back for the first time was as close as I’ll likely get to that “Wizard of Oz” moment when Garland goes from black and white to Technicolor. Ms. Ronstadt, wonderful as she was, seemed to sing in mono compared to Ms. Streisand in glorious, full-range, natural hi-fi.

Mr. Gabler is quite up front about not producing a full-fledged biography, of which there are several, and from which he cites many telling quotes and anecdotes for this study of Ms. Streisand’s transformations from duckling to diva, from self-doubt to determination to domination of stage, set, and studio (for better and worse).

More broadly, he explores Ms. Streisand’s place in, benefits from, and effect on recent tides in American culture. He finds her “part of the American consciousness” as few entertainers before, “validating a new kind of glamour, a new kind of star, a new kind of power.” Wrote the social critic Camille Paglia: “Streisand broke the mold, she revolutionized gender roles,” though some activists complain that she actually did little to aid their feminist movement.

Along with the social context, at which Mr. Gabler is always so adept, there are enough basic facts and juicy tidbits to satisfy anyone who has not delved deeply into Ms. Streisand’s story.

There was the young father who died when she was only 15 months old and left Barbra with an endless sense of loss and longing, and fears about her own early demise.

There was the mother, more competitor than supporter, insisting young Barbra had neither looks nor talent for the stardom she dreamed of. Resisting the girl’s first request to make a demo record of her singing, she agreed later when a demo by Mom was part of the deal.

And there was the stepfather named Kind, who wasn’t very, and persistently heaped greater praise on her half-sister, Roslyn, later a performer herself, though never matching Barbra.

All of which led Ms. Streisand to legendary levels of self-consciousness, self-doubt, then determined self-assurance and aggressive self-assertion, as many who worked with her later complained (the Jewish Woman Syndrome, some called it), though her inherent talent was hard to deny. “Sure she’s tough. But she has an unerring eye,” said the cinematographer for “Funny Girl” after she started telling him where to place the lights.

“Most people are followers. They need you to be sure,” the young star told the Newsweek critic Joe Morgenstern at the time. And this insistence on perfection — as singer, actress, and director — to balance all doubts about her (including her own) seems to have deep roots. “I was like this when I was 12,” she told another interviewer.

Mr. Gabler’s book is part of the Yale University Press’s Jewish Lives series, already surveying contributions to society by such co-religionists as Leonard Bernstein, Louis Brandeis, Albert Einstein, Emma Goldman, Lillian Hellman, Groucho Marx, and Leon Trotsky. As such it inevitably highlights quintessentially Jewish aspects of Ms. Streisand’s look, speech, and approach — to her life, profession, later liberal politics — and how they both hindered and helped her.

Of course the fields Ms. Streisand chose to conquer — Broadway, Hollywood, the popular music business — have long had significant, if not dominant, Jewish influence.

What Mr. Gabler calls the “haute Jews” then in charge at first doubted Ms. Streisand’s appeal to a broader audience, and some apparently felt personally uncomfortable with the particularly Brooklyn Jewish manner to which she clung. Later there was suspicion that some Jewish entertainment execs came to enjoy redefining American beauty.

For it soon became clear that Ms. Streisand’s actual history and determined image as the Plain Jane outsider who perseveres despite painful rejection — and prevails — was central to her increasing success across ethnic lines. It came through in her singing and acting, the underlying theme in so many of her hit films, although the word “Jewish” itself was often notably absent from reviews.

“Barbra Streisand has changed the bland, pug-nosed American ideal of beauty, probably forever,” wrote Gloria Steinem. After “Funny Girl,” more women were dressing with a Streisand look, even requesting plastic surgery to have noses like hers, Mr. Gabler reports. Not so much lately.

Ironically, Ms. Streisand’s casting as the star of “Funny Girl” — about the earlier iconic Jewish stage, screen, and radio star Fanny Brice — came despite the objection of Brice’s own daughter, Frances, not coincidentally the wife of that film’s famed producer, Ray Stark. She doubted that Barbra could capture her mother’s far more elegant, non-ethnic offstage style, including a nose job that prompted the famous Dorothy Parker quip that Brice “cut off her nose to spite her race.”

(It was, in fact, Irving Berlin in 1909 who first prompted Brice to affect the Yiddish accent that became her trademark, for a song he gave her for Ziegfeld: “Sadie Salome Go Home.”)

Ms. Streisand’s refusal of oft-suggested plastic surgery is seen by Mr. Gabler as being true to her Jewishness and to herself. He also quotes her as fearing the pain. But chapters later, in another context, he touches on what might have been the most important factor of all to a singer he frequently compares with Sinatra — her uniquely powerful, wide-ranging vocal magic. “It’s some messed up nasal thing,” she once said. “It just seems the right sounds come out.”

Ms. Streisand’s hearing was also messed up in a way that benefited her. The buzzing of tinnitus made her acutely aware of all sounds, including her own voice — “a gift,” she called it.

Mr. Gabler also quotes various masters of popular music on the dramatic way Ms. Streisand interpreted a lyric, with undertones of despair, defiance, and determination from her own life, as in her acting. Indeed, “I approach a song as an actress approaches a role,” Ms. Streisand has said.

But she is hardly alone in that approach. I once asked the former TV soap star who became the cabaret queen Andrea Marcovicci if she missed acting. Her answer, cleaned up for radio: “What the [bleep] do you think I’m doing up there?”

Beyond Ms. Streisand’s unique talent and temperament, Mr. Gabler concedes that changes under way in 1960s and ’70s culture, which she came to symbolize, also set the stage and boosted her success: the new feminism, celebrations of ethnic diversity, an anti-establishment spirit.

And she benefited as well from good timing in terms of music and technology. According to Wilfrid Sheed, the late Sag Harbor critic and music historian (“The House That George Built: With a Little Help From Irving, Cole, and a Crew of About Fifty”), Sinatra succeeded in large part because the microphones he mastered had gotten so much better, and radio had become a dominant entertainment medium.

Similarly, I would suggest, the ’60s boom in home hi-fi and stereo as Ms. Streisand exploded on the scene served her extraordinary vocal range far better than old AM radio or mono records ever could. And she entered America’s pop music mix just before the rock revolution all but totally banished songs of Broadway, Hollywood, and the Great American Songbook to niche status, though she still managed to score number-one albums in each of the last six decades.

Time also has benefited Barbra personally. With few heights left to climb she has found satisfaction with a less-driven life (relishing home design and architecture) and a love-at-first-sight marriage to James Brolin, a fellow actor but never one of her overshadowed co-stars.

She did no full-length concert for 20 years before her “One Voice” benefit in 1985, and for nine more before her multi-city tour in 1994. In 2006 she announced plans to tour again for a variety of liberal causes supported by her personal foundation, and she launches yet another tour next month, including back-to-back performances back in Brooklyn at Barclays Center.

If, for all her trailblazing, symbolizing, and redefining, it is not exactly a Streisand world we live in today, so be it. “She provided a metaphor — that Jewish metaphor,” Mr. Gabler concludes. “Barbra Streisand showed us, especially the outsiders among us, how to survive. She showed us how to triumph. And, perhaps above all, she showed us how to live on our own terms — just as she always had.”

Just to hear your cultivated voice good and strong

I’d serve a year in jail Yiddisha nightingale.

Won’t you sing me a song?

Neal Gabler’s previous books include “An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood” and “Winchell: Gossip, Power, and the Culture of Celebrity.” He lives in Amagansett.

David M. Alpern, creator of the “Newsweek On Air and “For Your Ears Only” radio shows, now hosts podcasts for the World Policy Journal from his house in Sag Harbor.