Illuminating Pollock’s Process at Guild Hall

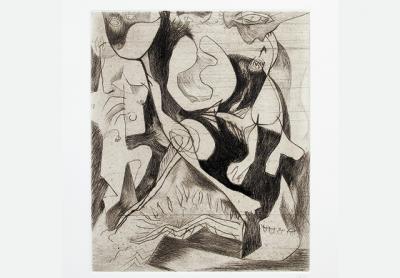

While Jackson Pollock’s poured and dripped paintings emerged in the late 1940s, his road there passed through, among others, Thomas Hart Benton, Picasso, Surrealists, and the Mexican mural painters, one of whom, David Alfaro Siqueiros, introduced him in 1936 to pouring and dripping liquid paint.

What is perhaps less well known is that he worked out the ideas for his paintings, including the poured works, not with sketches but through prints, including a large number of serigraphs.

In the brochure for a 1995 exhibition at the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center, the art historian Francis V. O’Connor wrote, “Pollock’s serigraphs, while a minor aspect of his oeuvre in comparison to the major paintings and drawings he created throughout his career, nevertheless served as rehearsals for the forms and effects he utilized in those masterpieces.”

“Jackson Pollock: The Graphic Works,” which will open at Guild Hall in East Hampton on Saturday and continue through Oct. 9, includes seven engravings from original plates made by Pollock in 1944 and 1945, and seven serigraphs from screens made by his brother Sanford in 1951. All the works belong to the Pollock-Krasner Foundation.

“While Pollock experimented with prints, it was not a medium he fully embraced,” according to Christina Strassfield, Guild Hall’s museum director and chief curator, who organized the exhibition. “He did not continually do prints, like Roy Lichtenstein, for example, who always did paintings and prints at the same time. In Pollock’s prints you see more control, more within the frame, as opposed to his mature paintings when he was working much more loosely on the floor.”

The prints in the exhibition are not the original ones he worked on. They were done posthumously under the supervision of his widow, Lee Krasner, in 1964 from the original copperplates and screens.

Helen Harrison, the director of the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center, noted that Pollock never made editions of the engravings. “He only pulled proofs. The proofs in various states and the plates themselves are in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art. As far as we know, the screens no longer exist.”

From a small edition of roughly 25 of the screen prints, a portfolio of six was for sale at Pollock’s 1951 exhibition at the Betty Parsons gallery. “They weren’t popular, and they didn’t sell,” Ms. Harrison said. “Pollock had a bunch of them. We have home movie footage from 1953 of three of them for sale at the Fisherman’s Fair for $50. Lee is holding one up for the camera.”

Ms. Harrison will have a print from the posthumous edition at Ashawagh Hall in Springs on Friday, the day before this year’s Fisherman’s Fair, for the 6 p.m. ceremonial investiture of Pollock as an honorary Bonacker. She will also give a free gallery talk on the exhibition on Aug. 19 at noon. Registration, which is required, is through Guild Hall’s website.