John Gruen’s 9/11

As familiar as John Jonas Gruen’s scenes from the aftermath of Sept. 11, 2001, seem on the walls of the education center at Guild Hall, there is something Old World and alien about them.

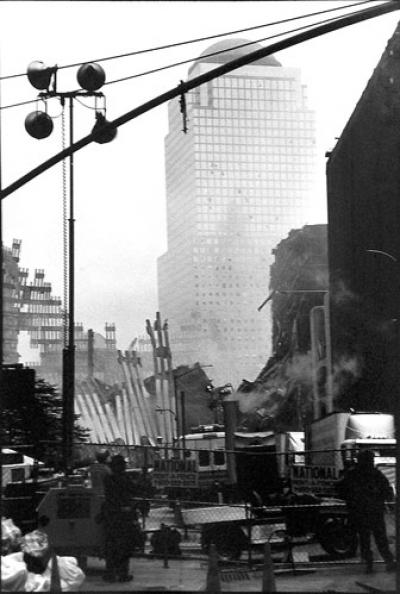

Part of it, no doubt, is the black-and-white film he uses. Yet, there is more, something odd and shadowy that makes it seem as though you are looking at photos taken in Europe during World War II. It is the sense of domestic war in them: the bombed-out ruins and grim tokens of hundreds of lives lost. There are not many people in the images of rubble, flags, shrines, and “missing person” posters. What people are shown are mostly in photographs of the known and soon-to-be-known dead. One of the eeriest images is of national guardsmen marching single file down a Manhattan block.

It looks as if in this country, on our soil, we were at war. But we were not then, at least not officially. What the show points out indirectly is that the decade of war that followed did not start right away. There was a pause and a reckoning.

We know this because the photos remind us so. There may be a Dunkin’ Donuts billboard with a flag and the slogan “United We Stand,” but those photographed participating in peace vigils in the park were speaking different words at the time, and definitely not vowing revenge.

A decade after the sights of those days, what is there to learn from them? Plenty, it would appear, but we might need even more time for the emotion to separate enough from the images in order to come to an understanding different from that immediate gut response that still arises when we see them.

At the time most of the photos were taken, the ruins of the World Trade Center were still smoking and standing, lacy shells of what was once deceptively impervious concrete and steel.

Mr. Gruen has said his instinct was to get down there as soon as he could and as close as he could, but even soon after the tragedy it was difficult to get near the site. Nonetheless, he did find some vantage points that provided a telling glimpse of the aftermath near Ground Zero.

A gaping hole where two 100-plus-story towers once stood left downtown denizens directionless and left skyline viewers to refill the horizon with the tentative memory of the buildings’ outlines. At the base of the F.D.R. Drive, entire lanes and exits were restricted to emergency vehicles, with improvised signs and traffic patterns making downtown New York seem like downtown Beirut in the 1980s.

Thankfully, no one can recreate the stench of burned flesh, fuel, and office supplies or the odd greasy dust left behind. Close to the site, it was like what one might imagine the mouth of hell to smell like. Farther uptown it became dispersed, but when the wind was right, the smell was back in your face, always a reminder. Residents south of Canal Street reported keeping their air-conditioners running through October just to filter it out. Many said they never got used to it.

As a soundtrack, there were bagpipes. For weeks, it seemed, somewhere at all times there was a fallen police officer or fireman being honored, as if whole departments had left us. In the park, cops were uneasy heroes, hesitantly returning overwarm greetings from a public they were hired to serve, protect, or subdue, if need be.

Mr. Gruen’s images of makeshift shrines of candles outside firehouses and police stations and in surrounding neighborhoods call up some of these sense memories. The flags depicted everywhere were, in fact, everywhere, sprung up overnight on every building in New York, the bigger or biggest representing the better or best.

Seeing, out of context and a decade later, the immaculate glass cube of the Chase Bank on 43rd Street and Fifth Avenue festooned with a flag almost as large as its facade seems surreal and even kitschy. But back then, it was highly appropriate, a tribute to lives lost and a symbol of a city’s and country’s resilience.

Mr. Gruen takes his photos in a street photographer’s style: casual, but not too detached. There is something disjointed about them, a bit of dissonance. They are photos taken in the pause of the half-beat. The sense is one of loss and of being lost, vertigo that did not go away for weeks or months, and which came not just from the events but from the radical alteration of all that was familiar around us.

The exhibit, one man’s take on the scene, may well serve as a mantel on which we can each hang our own experiences as they gradually fade from our grasp. Given Mr. Gruen’s ability to capture thoroughly the spirit of the time with just a few of these images, and his prescience in choosing subjects that can now surprise us with things we might not recall, I see nothing wrong with that.

The show is on view through Oct. 10.