Katie Beers: ‘A Community Rescue’

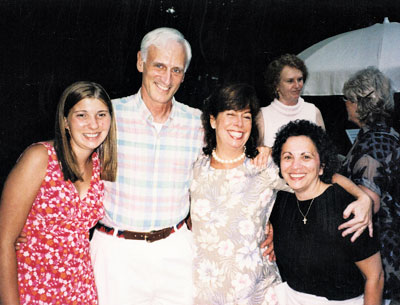

Twenty years ago this week, Katie Beers, who was kidnapped two days before her 10th birthday, was released from a macabre dungeon beneath a Bay Shore house where she had been held for 17 days by John Esposito, a family friend. She had already lived through years of neglect by her biological mother, Marilyn Beers, and sexual abuse by a man married to a surrogate mother with whom she was often left. But after her release, she was placed with a foster family in Springs, grew up here, and is now a wife and mother who wrote about her journey in a book released this week, “Buried Memories: Katie Beers’ Story.” Written with Carolyn Gusoff, a journalist who was a Long Island News12 reporter covering the abduction, the book not only provides the horrific details of Ms. Beers’s ordeal, but tells how she was able to recover and mature through a positive childhood and adolescence in a welcoming community. “The Springs School was a safe harbor,” said Mary Bromley, an East Hampton psychotherapist who counseled Ms. Beers regularly from the time she arrived here until she graduated from East Hampton High School and went off to college. The two remain close. In a chapter of the book detailing her therapy with Ms. Bromley, Ms. Beers says that “even now when I’m anxious I have a little bit of Mary with me.” “It’s a great story, in terms of recovery,” Ms. Bromley said of Ms. Beers’s journey. A psychotherapist who worked for 10 years in a special victims unit at St. Vincent’s Hospital in New York City, she was tapped to work with Ms. Beers by the county’s Department of Social Services, which was looking not only for a therapist experienced in working with sex crimes victims, but someone who could help prepare a child to testify at a trial. Ms. Bromley was with Katie through meetings with the district attorney, judicial hearings, and the trial of Sal Inghilleri, who had sexually abused her since she was a toddler. She testified clutching a teddy bear and Ms. Bromley’s hand. Mr. Inghilleri was sentenced to 12 years in prison and died there after being returned to jail for a parole violation in 2010. At first, Ms. Bromley said, she drove Katie to meetings UpIsland herself, but when that became a strain, the East Hampton Town Police stepped in, ferrying the two safely to and fro. The community embraced little Katie with “a collective sense of love,” Ms. Bromley said. “People respected her privacy and accepted her.” Between the Suffolk County District Attorney, James Catterson, who was personally involved in the case, Lt. Dominick Varrone, a detective who led the investigation into her kidnapping, an “amazing prosecutor,” sensitive case workers at Child Protective Services, and the Springs community, “she really had the best of the system,” Ms. Bromley said. “She would say, ‘the whole world is on my team.’ She often said this trauma was one of the best things that ever happened to her, because she got a good family” afterward. Everyone worked together in a united approach to help her heal. Katie Beers’s arrival at Springs School stands out for Chris Tracey as a memorable day in his 30-year career in education. A vice principal at Springs at the time, he and Peter Lisi, the school superintendent, welcomed the new student whose arrival was accompanied by a swarm of reporters outside. “We met with her that morning,” Mr. Tracey said. “She was sitting in the chair, and her feet didn’t even hit the ground.” “We tried to make her laugh and let her know we were her friends, and make her feel confident.” And then, as with any new student at the school, they walked her down the hall, where she became just another cherished member of Dolores McGintee’s fourth-grade class. Students and faculty had been briefed before she arrived, and for the most part, no questions were asked. Mr. Tracey later became an administrator at East Hampton High School, and also knew her as a student there. At both schools, he said, “Based on what I saw, I think she adjusted very well. She just blended in after a while.” “For many kids, they wouldn’t have gotten through it,” he said. “There was something special about this young lady — resiliency and courage.” “I could tell by the way she walked in, with a whole class watching her, that she was spunky,” said Debra Foster, who was a health and physical education teacher at Springs School when Katie arrived. “And it turned out to be true.” A couple of years later, when the sixth-grade health class got into discussions involving sexual predators, Ms. Beers volunteered to talk about the subject with her fellow students. “She ran the whole discussion,” Ms. Foster said. “She’s a very special young woman.” Ms. Foster told how, in the first few days when the media remained camped outside the school, Robin Streck, another student who was about the same size as Katie, put on the new student’s coat with a hood, and left the school in full view of reporters, acting as a decoy while Katie was taken out the back. Non-uniformed East Hampton cops stood guard around the school and at either end of the foster family’s street to make sure she would be left alone. “The whole community just put their arms around her and nurtured her, and helped to make her safe,” Ms. Foster said. In her early counseling sessions with young Katie, Ms. Bromley used art therapy techniques to “help her gain mastery over her feelings.” Ms. Beers produced drawings and paintings of the underground bunker in which she was held. It was under a hatch, topped by a 200-pound weight that led to a narrow, seven-foot shaft. She was held inside a soundproof box, two feet wide by seven feet long and three feet high, inside the dungeon. The only light came from a closed-circuit TV, on which she could see the police looking for her outside the house. Mr. Esposito, a key focus of the police investigation, finally confessed and led investigators to her. He was sentenced to 15 years to life, and will be up for parole in the fall. In an appearance on the “Dr. Phil” CBS TV show, which aired on Monday, Ms. Beers said she spoke at a previous parole hearing for Mr. Esposito, and believes he should spend his life in jail. The episode was titled “Young, Innocent, and Held Captive,” and was just one of a number of appearances and articles about Ms. Beers this week, coinciding with the release of the book. “I was 9 years old, and I had a funny feeling,” Ms. Beers said on the TV show Monday, as she described how Mr. Esposito had taken her to his house and locked her up. He chained her around the neck once he realized her wrists were too small to be restrained, raped her, and hit her. Tearfully, she described how, finally, he came into the dungeon followed by police. “I had the will to survive,” she told Dr. Phil. “You were a very street-smart, savvy girl,” Dr. Phil said to her. She was a bit like Tatum O’Neil’s character in the movie “Paper Moon,” Ms. Bromley said. “In some ways, she has a very strong constitution. And the ability for denial — both of which helped her.” “Had Mr. Esposito not come forth, I don’t think we ever would have found Katie,” Mr. Varrone said on the show. Support for Ms. Beers was widespread. Ms. Bromley has a whole bin of letters to Katie from children all over the world. “We went through some of them together,” she said. Still, “it was not easy for her,” the therapist said. There were setbacks, for instance, when photos appeared in the newspaper of her abusers. Together, Ms. Bromley and Ms. Beers read “17 Days,” an earlier book about the kidnapping by Arthur Herzog, a Wainscott resident who died in 2010. After learning that a 75-year-old Manhattan man who had also been kidnapped and held underground had a house in East Hampton, Ms. Bromley contacted him and asked him to meet with Katie, believing that they could help each other. It was remarkable to learn, she said, that they had both employed the same survival strategies, such as reviewing the moments of their lives while in captivity. “He talked to her about the ability to get angry, and she talked to him about forgiveness.” At a press conference at Hofstra University in Hempstead on Tuesday with her co-author, Ms. Beers reunited with Detective Varrone and with Ms. Bromley. She normally visits East Hampton several times a year, but, she said in a phone interview on Tuesday, as a mother now of two young children — a boy, 31/2, and a girl, who is 17 months — it has lately been only once a year, for an extended week in the summer. She has been married to her husband, whom she met in college, for six and a half years, and works at an insurance agency. She is still occasionally in touch with her biological mother and brother. Her parents — the Springs couple that took her in as a foster child — continue to maintain their anonymity. They supported her decision to write the book, Ms. Beers said Tuesday, but desire to remain out of the limelight and allow the focus to remain on her and her remarkable recovery. Though she was not formally adopted, “they are my parents through and through,” Ms. Beers said during a phone interview on Tuesday. The family had three older children, and, upon arrival in Springs, Katie was set into a structured, normal family routine, with her foster parents dropping her off at school and expecting her to pitch in with household chores. Many East Hamptoners have posted greetings and messages of encouragement on her Facebook page, set up in advance of the book release. Since the age of 10, just after her ordeal, Ms. Beers knew that someday she wanted to write her story. “I wanted people to see that there is recovery after trauma,” she said Tuesday. “Until eight years ago I didn’t realize how much of a, quote unquote, media sensation I was,” she said. “The community of Springs was instrumental to my recovery . . . keeping me safe,” she said. Everyone “really just gave me a chance to be a kid, and grow up.” Ms. Gusoff said that in the book she calls what happened “a community rescue.” They hope to arrange a book signing on the East End, Ms. Gusoff said. Ms. Beers said Tuesday that she would love to become a motivational or inspirational speaker, spreading hope to those who must try to recover from an ordeal. But, she said, “I’m very happy with the life that I have in central Pennsylvania.” Ms. Beers learned to develop trust in people, and a sense that “the universe is benevolent,” Ms. Bromley said earlier this week. “And she really accomplished that with her foster family, certain friends, a boyfriend here, and with me.” “And she put away a guy,” she added. “She’ll have me for as long as she needs me,” Ms. Bromley said. “I’m honored to do this work. Therapy is about love. And if it isn’t about love, it isn’t going to work.” In a poem, “For Katie on Her 15th Birthday,” Ms. Bromley wrote to her: “It has taken many years to crawl out of that hole and there have been many strong arms along the way to pull you out.” “You have come up into the light,” it later says.