Katrina as a Warning: Hurricane season is upon us once again

Jack and Barbara Connors, former South Fork residents - he is from East Hampton, she from Montauk - packed up two carloads of their belongings along with two dogs, a cat, and a bird and left their house in Slidell, La., outside of New Orleans, early this week to ride out Hurricane Katrina at a naval base in Mississippi.

Ms. Connors's mother, Blanche Riley of Montauk, said that it wasn't until yesterday that she had contact with her daughter and son-in-law. Although the Connors have returned to their neighborhood, which didn't suffer the brunt of the storm, and "didn't lose a thing," according to Ms. Riley, they are virtually prisoners in their house.

They will be without electricity for three months, Ms. Riley said yesterday. And though they have enough food to last a few days, they cannot buy gas, and A.T.M.s are not working. Stores in the neighborhood have been completely demolished. Their daughter's school will not reopen until Dec. 1.

"Everybody on the block has somebody missing," Ms. Riley said. "It's total chaos." She said she was relieved to hear that her family is safe, but added that they might have to leave Louisiana in Katrina's aftermath.

As the days of Indian summer approach and storms batter other coasts, South Fork residents have one thing on their minds: hurricane season. Although the long-range radar outlook has shown relatively clear conditions lately, experts say that the warm seas will churn up some nine hurricanes through November.

The hurricane season started in June, but the northern Atlantic states see the worst of it in the fall, and the East End must again brace itself for the major storm that is said to be statistically inevitable.

Richard G. Hendrickson of Bridgehampton, an observer for the National Weather Service for over 75 years, said, "We will have another one, but I don't know whether it will be this year or 20 years from now. The longer you wait, the closer you get to having another one."

Of the nine storms predicted by the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, between three and five are expected to be classified Category 3 or higher on the Saffir-Simpson hurricane scale, with winds of at least 111 miles per hour.

A storm of Category 3 magnitude could cut into the South Fork at Canoe Place, Napeague, Fort Pond, or Ditch Plain, creating islands as well as new inlets. If winds reach 131 miles per hour - the definition of Category 4 - the storm would "flatten everything from the present shoreline back across the few dunes remaining," Mr. Hendrickson said. Such a phenomenon has not occurred here for 190 years.

Experts say that we are 11 years into a 30-year cycle of higher-than-average storm expectations. According to NOAA, seven tropical storms appeared in the Atlantic Ocean during June and July alone, a record. Low winds and warm ocean temperatures have been blamed for their frequency.

Much of this problem is caused by global warming, according to Mr. Hendrickson. On Aug. 22, he recorded the 14th day of the month with a temperature exceeding 90 degrees. The air temperature affects the temperature of the sea, he explained.

Mr. Hendrickson said that several squalls have already formed off the coast of Africa this season. Some of them dissipated, but others moved toward Central America, the Caribbean, and even Texas, at the west side of the Gulf of Mexico. Not until the storms get as far west as the Caribbean do American forecasters begin to track them consistently, he said.

Last week, weather forecasters watched tropical storm Katrina as it picked up steam traversing the Caribbean, turned into a hurricane, and reached Category 4 hurricane status as it passed through Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama. New Orleans was evacuated in anticipation of 150 mile-per-hour winds on Monday. Lake Pontchartrain flowed over hundreds of towns surrounding it. The coastal cities of Biloxi, Miss. and Gulfport, La., appear to have been all but completely destroyed. The Gulf Coast was hit earlier this season by Hurricane Dennis.

Katrina's effects could reach as far as the Great Lakes, according to the National Hurricane Center. Cleaning up after the disaster could cost over $20 billion, and death tolls continue to rise.

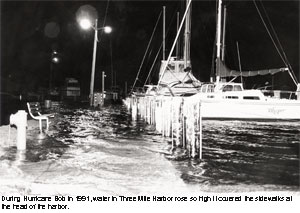

It has been 14 years since a hurricane came close to touching the East End. In 1991, Hurricane Bob veered east of Montauk, but caused a fair amount of damage anyway, uprooting trees and intensifying the ocean's swell.

Before that, Hurricane Gloria crossed the middle of Long Island in 1985 as a weak Category 3, knocking out power on the East End for up to two weeks for some residents. Because it hit during low tide, experts say, the twin forks were not damaged too critically.

Neither, though, compared in strength or magnitude to the Hurricane of 1938. The Category 3 storm came with little notice on a warm September day, battering the East End. It is said to have killed as many as 600 people. A tidal surge and high winds crushed some houses and tore the roofs off others. That morning, the Coast Guard station had received a warning only of relatively mild winds, of the sort found on the fringes of a hurricane.

It is highly improbable that we could find ourselves surprised by a hurricane today. NOAA flies airplanes into the eyes of the storms to gather information on them. But it is local weather, according to NOAA, that determines the landward movement of hurricanes. So although a hurricane can be carefully tracked, when and where it makes landfall cannot necessarily be predicted.

Although death tolls have decreased in recent hurricane history, the cost of related damage has increased dramatically. Hurricane Andrew, which hit Florida, Louisiana, and Mississippi in 1992, does not appear on the list of most deadly hurricanes, but it set the record for expense caused by damages - it cost $15.5 billion to clean up after the storm.

According to the Insurance Information Institute, hurricanes last year, none as catastrophic as hurricanes Andrew or Katrina, caused damages well into the billions of dollars.

Local governments, including East Hampton Town, enforce Federal Emergency Management Agency standards for all houses built in the flood hazard district, which includes areas along the Atlantic Ocean, Block Island Sound, and some smaller bodies of water such as Three Mile Harbor.

First floors have to be raised above the 100-year flood height - a tide whose chances of being equalled in 100 years are 1 percent. Floodproof construction, meant to prevent water from tearing houses from their foundations, and breakaway walls are also required. Those who live in flood hazard districts are required to buy flood insurance.

In 2000, the Long Island Power Authority formed a major storm review panel, meant to ensure that power is restored in a timely fashion to those who lose power during storms. After Hurricane Gloria, the Long Island Lighting Company (since replaced by the Long Island Power Authority) faced criticism for the length of time it took to restore power.

Although FEMA construction standards can protect waterfront houses from sustaining the kind of damage seen in the past, there is no sure way to avoid other dangers posed by high winds, such as falling trees. Covering windows with plywood can be effective in some situations, but flying debris can damage more than glass.

Hurricane safety tips and recommended procedures are listed at the Web sites of NOAA, FEMA, and the Red Cross.

Mr. Hendrickson said that for the moment, at least, he sees "nothing we should be alarmed about" on the hurricane front. But in the wake of the current drought, he expects a strong northeaster to blow over the South Fork within two weeks. "We have to watch our weather very closely," he said.