Kid Marlowe

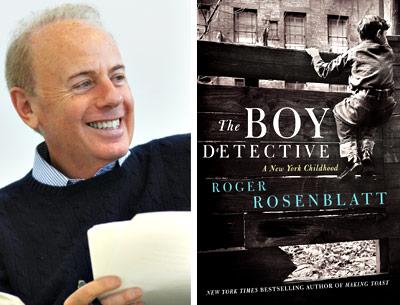

“The Boy Detective”

Roger Rosenblatt

Ecco, $19.99

Roger Rosenblatt may have just invented a beguiling subgenre — call it mem-noir — in which remembrance loops along a dark trail of switchbacks and time-jumps like a memoir narrated by an erudite, shape-shifting shamus. The protagonist is the 11-ish Roger, who prowls his Manhattan neighborhood and his childhood as if he were a private eye. Lurking in the shadows is the 70-ish Roger, the real gumshoe, trying to figure out how everything and nothing has changed.

“I am moved by the young women successes caressing their iPhones,” he writes, “as I was moved by their grandmothers leaning out the windows, with their deflated breasts on the rotted sills, and shrieking for their dogs to come home.”

Mr. Rosenblatt’s last two memoirs were more traditional, and more accessible in their literary yet self-helpful way. They were Mr. Rosenblatt as reporter and then philosopher, two roles he has starred in throughout a splendid career as writer, teacher, and performer. In the best-selling “Making Toast,” he described how he and his wife, Ginny, became parents again after the sudden death of their daughter. In “Kayak Morning,” he meditated on the grief they eventually had to confront after dealing with practicalities.

“The Boy Detective: A New York Childhood” is different, impressionistic, whimsical, and deliciously stuffed with description, commentary, asides about books, religion, movies, friendship.

The descriptions alone make the case. Old Roger, who has been teaching a memoir-writing course a few blocks uptown, strolls onto Young Roger’s streets around Gramercy Park, still the jewel of the neighborhood. The park is private and locked. The Rosenblatts, who lived across the street, had a key to the park, which I, a nearby — but not near enough — resident for 25 years, do not. I have always wondered if the reason I don’t like the restricted and pristine park is because I am excluded from it.

But Mr. Rosenblatt, an insider, explains my feelings to me. He describes its “studied civility” and its “smug prettiness.” He writes, “. . . for all its insistent bourgeoisie dignity [it] remained joyless even at Christmas, when the tree blazed in the park with its familiar set of lights and the accordionist from Calvary Church led the residents in the routinized singing of carols.”

Like Marlowe or Spade, Mr. Rosenblatt is precise, laconic, remarkably unsentimental. He floats potential novels in brief passages.

His father, a doctor and “wanna-appear” WASP, once said to him, “Roger, that’s no way for a twelve-year-old boy to behave.” Roger replied, “Dad, I’m eight.”

Or,

“Writing in war zones, I was made afraid not in Sudan or Beirut or even Rwanda. . . . In Belfast, however, I felt a fear so deep it froze me like Emily Dickinson’s snake. And it was born not of bombings or shootings, but rather of the hatred in the air, colder than the day is now, by which one knew how dark the soul could turn.”

Or,

Controlling his fury to this day over the firing of a favorite teacher for not inflating grades, he writes: “Here was a school whose Quaker educational vision allowed for the admission of one black student, just one, in the mid 1950s, and whose faculty included several outspoken anti-Semites, a couple of floozies, a leering pedophile who used to loiter around the boys locker room, at least two alcoholics who came to work with booze on their breath, a French teacher who spread rumors about the students, and a biology teacher who taught us that if a fat woman married a thin man, they would have an ordinary-size child.”

For all his side-of-the mouth “Are you with me, pal?” the erudite, shape-shifting shamus has the soft spot of his kind. He confesses: “For all his hard-boiled patter, he believes that love defines us, that if love prevailed over all competing emotions in the first place, there would be no cupidity, no crime.”

So mem-noir finally loops back to the messages of all Mr. Rosenblatt’s stories: “I’d pick the heart over the head any day, because everybody is smart, you know, but not everybody is kind.”

Robert Lipsyte, the ESPN ombudsman, is author of a memoir, “The Accidental Sportswriter.” He splits his time between Roger Rosenblatt’s old Manhattan neighborhood and Shelter Island.

Roger Rosenblatt teaches in the M.F.A. program at Stony Brook Southampton and lives part time in Quogue.