The Lady Vanishes

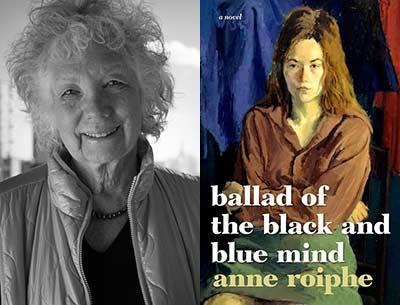

“Ballad of the Black and Blue Mind”

Anne Roiphe

Seven Stories Press, $23.95

When I read books for a review, I often put a check mark in the margin of text that I find smart or funny or well written or otherwise of interest or merit. Suffice it to say that my copy of “Ballad of the Black and Blue Mind,” Anne Roiphe’s latest novel, is littered with check marks.

It is a quintessentially New York novel (and shameless urban chauvinist that I am, I really mean a Manhattan novel in much the same way that Woody Allen’s “Manhattan” was a Manhattan movie). It is Jewish, intellectual, Upper West Side, arty, upper middle class, Hamptons-y, and deeply concerned with psychoanalysis.

Dr. Estelle Berman lives alone with her cat, Lily, in a huge old apartment on the Upper West Side. She is an M.D., a prominent psychoanalyst, head of committees, deliverer of psychoanalytic papers at professional meetings, supervisor to young analysts at her institute. She is a widow with a grown son. And she is beginning to lose her memory.

For a psychoanalyst, a loss of memory is not just a personal horror, but a professional death knell. Remembering particulars and minutia about the lives of one’s patients, knowing the names of their cast of characters (parents, children, pets, friends, bosses), recalling important events in their life stories, these are the things that allow a psychoanalyst to do her job. Dr. Berman tries to continue her work, but patients, colleagues, and supervisees begin to take notice of her increasingly glaring lapses.

“Dr. Berman referred Adrienne [her patient] to the best OBGYN doctor at her hospital. It started right then. Dr. Estelle Berman kept forgetting the name of the OBGYN. She thought the name was repressed because she was jealous that her own time for procreation was long gone. She thought it was a sign of how difficult it was to accept the aging body and the narrowing of the road. But it rapidly became more than that and the list of forgotten places, dates, names, directions, affiliations, faces became longer and longer. In the privacy of her bedroom, she knew what was happening, but as soon as she knew she ignored what she knew. It must not, it could not, and it should not be. In her kitchen in the Hamptons, the housekeeper tipped over the sugar bowl on the counter and Dr. Berman entered to see a swarm of ants in the sugar, black spots on pure white, and she knew what was happening in her brain, but she would tell no one.”

The book centers not just on Estelle Berman, but on the life stories of several patients, both hers and those of Dr. Z. and Dr. H., who are a kind of Greek chorus and observe Dr. Berman’s decline and her foibles in italicized dialogue at the ends of chapters.

Dr. Z. said to Dr. H., Did you see the necklace Estelle was wearing tonight? . . . It looked like diamonds and emeralds and quite extraordinary.

Dr. H. said, Real?

Dr. Z. said, Probably not. Who would wear such a thing to a discussion of “Femininity and Fantasy in the Silent Film.”

There is a strong parallel between fiction and psychoanalysis. Both — if done adroitly — are concerned with narrative, with gradually fleshing out and organizing, and not only making a life story emergent, but also making sense of a story. Ms. Roiphe has a masterful touch with both story and psychoanalytic thinking. Her portrayal of analytic sessions, the internal musings of analysts (we view sessions with Estelle and Drs. H. and Z.) and their patients, is wise, insightful, and knowledgeable.

Unlike some fictional portrayals of psychotherapy/psychoanalysis (e.g., “In Treatment” or “The Sopranos”) where I often cringe and think, “Wow, I would never say that to a patient,” Ms. Roiphe really gets and illustrates precisely what and how things are done in a good therapy. She is acutely aware of the stately pace of most of the work: “It would take a long time and multiple gentle hints before Mike Wilson might see this himself, but Dr. H. would try in time, because he believed it was true and truth was the antibiotic of the mind.”

Dr. Berman’s young supervisee thinks about the sexuality of one of his patients, “He wasn’t allowed to just tell her that. He would have to wait until she told him.”

Each patient in the novel is in a way a separate short story. There is Justine, the movie star daughter of a colleague. She “had the white blonde hair of a Swedish child and the black eyes of a Dostoevsky heroine and those eyes blinked at Dr. Berman nervously.”

“Justine had already tried to drown Justine in a river of vodka.” And she steals things. “Don’t steal anything before our next appointment,” says Dr. Berman.

There is Anna Fishbein, home from college, depressed, unhappy. Dr. Berman wonders if there was incest. Anna is a self-cutter: “. . . the cuts on her arm, a lineup of cuts, a few bandages wrapped all the way around the forearm where the cuts had been particularly deep.”

Mike Wilson is a retired CBS newsman, a widower in his 70s who has lost any desire to continue without his beloved wife. He wants to die, “but not quite yet.”

I understand, said Dr. H., you haven’t been feeling so well.

No, said his new patient. I haven’t.

A woman, thought Dr. H., would now begin to speak. A man would wait to see if it was safe. A man would make sure the other man in the room would not be dangerous. A man would stay on his side of the wall until he could not any longer. Dr. H. said, I understand that you lost your wife.

In one of the most poignant sections of the novel, Dr. Berman treats a patient named Edith “born with large bones and wide hands and feet and eyes the color of the Caribbean Sea at sunrise.” Plump as a child, at some point Edith becomes monstrously obese — “her stomach stretched, her bowels tight, her shame covering her, inflaming the sores between her legs that came from the chafed flesh that surrounded her vagina.”

“. . . Dr. Berman had sat opposite Edith quietly for many months. She had leaned forward to hear her when her voice had been almost inaudible. She had listened to her talk of diets and her shame at the gluttony she only partially disclosed. She had given Edith her full attention, and as a result the predictable had happened. A small space had opened in Edith’s mind where she sometimes thought of things to tell Dr. Berman. And in that small space something new was growing, was it a small bud, a small new tender shoot of affection: was the word for it love and what did that love contain? Edith didn’t know but it brought her hope, this feeling, and it belonged to her and was the gift she wished to give to Dr. Berman and this new feeling made her bring in her poems. . . .”

It is 20 sessions before Edith actually gathers her nerve and takes the poems in three notebooks out of her bag to give them to Dr. Berman. And a few days later Dr. Berman, in her increasing dementia, unknowingly throws them out. At the following session Edith ever so tentatively asks about them.

Dr. Berman said, I will read them when you give them to me.

Edith was silent. She looked all around the office for her three notebooks. They were not on the table behind the couch. They were not on the windowsill.

I gave you my poems, she said in her smallest voice.

I have no poems of yours, said Dr. Berman, quite certain.

The novel is indeed black and blue and full of melancholy and sadness and pathos. Many of the patients are struggling with difficult life issues, divorce, disease, loss, emotional trauma. And behind all is Dr. Berman’s own decline, what eventually becomes a dignity-robbing and horrible decay into what her son thinks of as his “vanishing mother.” Not exactly the stuff of summer beach reading, but wise and well written and at times enormously moving.

Michael Z. Jody is a psychoanalyst and couples counselor with offices in Amagansett and New York City.

Anne Roiphe had a house in Amagansett for many years.