Leonardo da Vinci and the Birth of the Modern

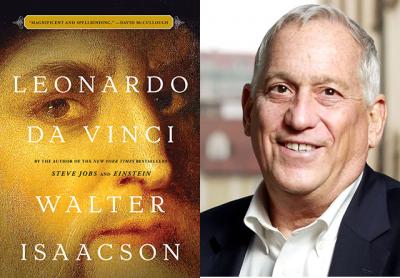

“Leonardo da Vinci”

Walter Isaacson

Simon & Schuster, $35

Unfinished, abandoned, fanciful, and failed are hardly the words we associate with genius in today’s results-oriented society. So it is a good thing that Leonardo da Vinci, a true Renaissance man, did not come of age in the 21st century. We would snicker at the thought of him, even as we partook of the modern iterations of his inventions or the things that became possible after adapting his ideas.

It is almost not worth reviewing Walter Isaacson’s biography “Leonardo da Vinci.” Already a best seller in pre-sales in one category on Amazon as of this writing, the book has been optioned by Paramount for Leonardo DiCaprio in what might be the most unimaginative casting ever delivered by Hollywood.

Captured by the author who brought insight and relatability to subjects such as Albert Einstein, Benjamin Franklin, Henry Kissinger, and Steve Jobs, Leonardo in Mr. Isaacson’s hands is a dreamer who imagined buildings, inventions, sculptures, and paintings so perfect they could often exist only as ideas. And for Leonardo, the working out of the idea, the planning, the sketching, and the design often were enough. His boundless curiosity didn’t allow him to tarry too long on one particular thing; there was always something new to question, discover, or solve.

The things that fascinated him — the movement of water, flight, atmosphere, engineering, arms and armaments, the movement of bodies, and the curl of human hair — are repeating elements in his art and design work throughout his life. An overarching theme of the book is that for him the forms of nature are repeated in humans and share a similar relationship to geometry and other physical properties related to science. He saw the analogy as a spiritual connection, and it became a leitmotif in his paintings. Similarly, he thought that the bodies he was representing should evoke their emotions.

He was not the first artist in Italy in the 15th century to tackle complex problems of design, be they buildings or technological innovations. Brunelleschi was one predecessor, famous for designing the dome for which the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence is known. Leonardo was also not the first artist to dissect cadavers to ascertain the most accurate way to depict the human form. Yet he channeled the most advanced ideas and knowledge available to him into breakthroughs inconceivable to those before him.

Similarly, artists had been analyzing perspective in previous decades, yet he refined not only how objects were placed in a receding background, but also realized that those objects farther away needed to be in softer focus, in different shades and tones of color, and eventually even blurry to replicate true optical experience.

Not seeing hard outlines in nature, he emphasized the curves and boundaries of figures with sfumato, a smoky atmospheric shadowing that separated forms from each other and from their surroundings. In examining paintings completed in the years immediately before his masterpieces and in the studio of artists like Verrocchio, in which he worked, it is clear how revolutionary his contributions were to the representation of the human form. Artists like Michelangelo and Raphael were able to achieve more ambitious projects, but without his example, it is not guaranteed that they would have developed as completely as they did into High Renaissance masters.

What was Leonardo’s problem? Mr. Isaacson doesn’t attempt to diagnose him definitively but suggests that had he been around today he would have likely sought treatment for some kind of attention deficit disorder or some other imbalance. He was known to have ups and downs, periods of extreme activity and productivity and then indolence and artistic blocks, driving his patrons mad.

Charming, attractive, erudite, and foppish, he was welcome at court, in art studios, and in the workrooms of the most accomplished mathematicians and scientists, who also called him a friend. He kept a retinue of young apprentices, of varying talents and attractiveness, some of whom became lifelong companions.

Leonardo was a perfectionist who also moved around quite a bit, serving the courts of the Sforzas in Milan, the Borgias in Florence, Pope Leo X in Rome, and King Francis I in France, where he died in 1519. Rather than leave his unfinished painting commissions behind, he often packed them up to continue working on them, which is why the Louvre has a significant cache of his paintings.

Mr. Isaacson probes all of the artist’s papers, seeks out every extant work, and reads the scholarship of those who have addressed the artist previously to come up with a full and engrossing profile of the artist, from his illegitimate birth in 1452 in Anchiano, Italy, to his dying breath as one of the most revered individuals of his time.

The author moves fluidly between the scientific inquiries of Leonardo’s notebooks and the artistic achievements in his sketchbooks, and carries the same themes, such as the artist’s boundless curiosity and inquiry, through them in a way that does not seem too facile or overapplied.

Confronted with the endless schemes and unrealized projects in his notebooks, Mr. Isaacson concludes, in light of some of Leonardo’s later failed water projects, that “in order to be a true visionary, one has to be willing to overreach and to fail some of the time. Innovation requires a reality distortion field. The things he envisioned for the future often came to pass, even if it took a few centuries. Scuba gear, flying machines, and helicopters now exist. Suction pumps now drain swamps. . . . Sometimes fantasies are paths to reality.”

The book is organized primarily chronologically but also thematically, and an early section that lays out the major themes guarantees that they will be repeated later to explain specific projects. This makes “Leonardo da Vinci,” at more than 500 pages, a bit more swollen than it needed to be. There was a time when readers simply went back to the earlier parts of a book if they had questions about the material covered.

The author also inserts his opinion about the quality and authenticity of Leonardo’s artworks, which seems intrusive when the best scholars and connoisseurs now and in history have preceded him. But this is not an academic work; there is no need for Mr. Isaacson to defend his credentials. He presents an exhaustively researched and thorough book, taking a modern look at a man who helped usher in the notion of modernity.

Walter Isaacson, a former editor of Time magazine, has spent summers on the South Fork for many years.